Aquarium Fish and Invertebrates: Is there space for a global standard in commerce? Part I - Getting them from there to here

by Peter Rockstroh

When a speaker or writer wants to vilify a group of people without naming anyone in particular, these days they invariably reach for an abstract umbrella term that covers almost everyone. This is especially true when they don’t know who in particular is to blame yet believe all involved share some responsibility.

Freshwater aquascapes are a highly challenging form of gardening, one that requires a profound knowledge of aquatic plants, light, filtration, water chemistry and all things aquarium-related. As the aquaria used for this part of the hobby become smaller and smaller, concentrations of any product become harder to handle. A slight miscalculation and your prized Zen Garden turns into a vegetable soup. Despite this risk and because current conditions that include increasing cost of living space and other contemporary lifestyle limitations, nano aquariums have turned into one of the fastest growing segments of this industry. Image: Aquascape and Photography ®David Bono.

Such is the case with the global aquarium trade, a term that includes–depending on who you ask–anyone from fishermen living in isolated areas through to large importers/wholesalers that distribute aquarium fish to pet stores or via online sales, together with their tropical fish-loving end buyers around the world. If you pose the same question to people unfamiliar with the inner workings of the aquarium industry the answer might include whalers, NATO, the creature from the movie “The Shape of Water” and the guy from the Old Spice Aqua Reef commercial.

There is an apt saying in Latin America about the blame game: “It’s not so much who’s at fault, but who’s going to pay”.

The global aquarium trade is best known to the people who wrote the book about it, or rather the books, as this topic has been discussed for quite some time. Fishing for the aquarium trade is registered by United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Program (FAO) as part of a country´s statistics on fisheries. Measured like all other aquatic resources, by weight, it is insignificant.

Colombia, for example, registered a nationwide production of fisheries and aquaculture of 187,500 t/tons in 2017 (FAO, 2019), of which 53% (100,000 t) were farmed fish. Of the remaining 87,000 t, continental freshwater fisheries have contributed yearly between 20,000 – 30,000 t during the last decade, a dramatic descent from the 60,000 t mark it reached at the end of the 1980’s. This amount corresponds mainly to large catfish and cichlids from the Amazon, Orinoco and Magdalena rivers that reach urban markets throughout the country. In short, Colombia’s fisheries are roughly 33% oceanic and 67% aquaculture and inland freshwater fishing.

For comparison, the Philippines, one of the largest exporters of marine ornamental fish, in 2019 had a total fisheries production of 4,421,220 t. Aquaculture, like in Colombia, made up for exactly 53%, and the rest were municipal fisheries (carried out from boats <10’/3 m) and commercial fisheries (boats >10’/3 m) (PSA, 2020). Ornamental fish added 5,216 t to the yearly catch, representing 0.12% of the country´s fisheries (Muyot et al., 2018).

The last FAO report (2019) that also included Colombian ornamental fish, made reference to the 2003 value of ornamental fishing that registered 122 t, equivalent to 20,305,000 individuals with an export value of USD 4.60 MM (Ajiaco-Martinez et al. 2012). Despite these fairly big numbers, those 122 t were only 0.065% of Colombia’s total fisheries industry.

Although insignificant as a percentage of the industry, when this weight is converted to numbers of individuals, a good-sized yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) for example, is equivalent to about 168,000 cardinal tetras (Paracheirodon axelrodi).

Wild collected Orinoco or Altum angelfish (Pterophyllum altum). Image: ©P. Rockstroh 2021.

If you hook and land a 550 lb/250 kg yellowfin tuna in much of the Developed World you might make the local news. If 168,000 cardinal tetras are left one night in their boxes out on the tarmac of any northern hemisphere airport because someone didn’t fill out the forms correctly for them to be loaded onto the connecting flight and die, the global aquarium trade will almost certainly be in the news with more bad press coverage.

Again, the numbers representing the aquarium trade as a percentage of global fisheries are very small but they can still generate plenty of noise. The difference is not only in the numbers. The difference lies in the expectations. Ornamental tropical fish are meant to arrive alive and be kept alive, while the other 99% plus of commercial fisheries are expected be consumed postmortem.

For several reasons, the global aquarium trade’s reputation among the general public has suffered over the past two decades. Damaging practices, such as cyanide fishing for tropical reef fish, has a strong negative impact on target species as well as on other animals caught within its drift and also on the coral reef itself. This practice has been widely reported on by global media outlets as well as many NGOs. The environmental impact and optics of the continued trade in “drugged fish” destined for global aquarists are, simply put, terrible. While the use of sodium cyanide to capture fish is forbidden in many countries it still isn’t easy to prove whether fish were captured using this product since there are still no inexpensive commercial test kits on the market. But it isn’t impossible to find evidence of residual cyanide either. As improved test procedures for detecting cyanide traces become less expensive and more readily available, they will almost certainly be employed by both wildlife inspectors and importers in northern countries to rapidly and effectively block future international trade of reef fish caught with this poison (Trager, 2017).

Freshwater fish carry a lot less troublesome baggage than tropical marines because a much larger percentage are captive bred, many of them outside country of origin. But inland wild-sources fisheries also have sustainability issues. With tropical ornamental fresh and saltwater fish, the main negative impact on these resources is the unacceptably high mortality rate during transit from point of capture to exporter. In both cases, it begins in poor rural communities, invariably without access to education or other viable income-generating alternatives. And by sheer luck some of these people live in biodiversity hotspots.

On-site workshops designed to reduce mortality in the aquarium fish trade are a never-ending educational process for both teacher and students. This is a street in a typical fishing community near the Amazon in Colombia. A year after their first workshop some of the participants decided to remove the foam flotation cylinders to reduce the cost of the cages. As can be seen by the mud-stained line on the outside of all of the houses, the water rose 15’/4.6 m higher that year than it had in many decades. The remaining floating cages in this community are now tied to some very tall trees, because, “you never know…”. Image: ©Peter Rockstroh 2021.

They live in places like the outer Marshall Islands, coastal Sudan, the shores of Lake Malawi or in the southwestern Orinoco lowlands, and when they stick their heads underwater with a diving mask on, they see fish.

Mind-blowing fish.

And when they lift their heads and look around at their surroundings there is not much else to trade with the outer world. They could stop catching fish for the aquarium trade, but their other available legal options would likely have a much worse impact on the environment. These people live there and know the area like the palm of their hand. They have the right skillset to find and catch beautiful fish. They don’t have the option of learning how to code in order to work in a well paid, non-existent job in a nice, non-existent office in the places where they reside.

Images shown above were taken at a tropical fish collection point in the field in the Dept. of Guainía, Colombia. The most efficient and least expensive solution to keeping fish healthy in fresh water is hanging net cages that function as temporary holding pens in a lake or river. To reduce the risk of losses, this particular fisherman built a large holding pond for several net cages in a small branch off the main river. The entire family helps keep the business running smoothly. Images: ©P. Rockstroh 2021.

A pair of harlequin shrimp (Hymenocera picta). Two species of harlequin shrimp are very popular among living tropical reef tank owners despite their very specialized feeding habits (they are starfish parasites/predators). In a significant achievement, harlequin shrimp have recently been bred and successfully raised in U.S. aquaculture. Image: Steve Childs 2006/Creative Commons 2.0.

Current social trends, the impact of COVID-19 and increased restrictions on keeping cats and dogs in apartments have stimulated interest in a wide variety of hobbies, home decoration (aka the nesting trend), collecting exotic houseplants and fish-keeping. Within the aquarium hobby, planted freshwater aquariums and living reef tanks in their nano versions have stimulated a wave of interest in high-tech, small size displays of habitat systems that include communities of small dwellers of these aquascapes.

If the aquarium fish trade is to continue growing and keep up with these interests, it will have to change and focus its efforts to demand policies that are supported throughout the value chain and address every possible step that helps reduce its impact on wild fish populations.

Clearly, it will take more than just eliminating cyanide fishing to make this industry sustainable. It will require training and supervision of fishermen, middlemen and exporters to establish traceability of the catch. Some threatened or vulnerable species will need a fisheries management approach of breeding areas and nurseries for fry, as well as seasonal catch restrictions for key species and populations. It will be necessary to further promote cooperation with aquaculturists and mariculturists to reduce pressure on wild populations and establish these programs at the source. And it will have to be developed, implemented and managed by participants in the trade if it is to be accepted as a fair solution to keep the hobby growing over time. See the local economic impacts of the 2018-2019 Indonesian blanket ban on all their live coral exports after it was determined that a few unscrupulous local exporters and coral farms were laundering wild coral fragments for clear evidence of the dangers of having anti-aquarium forces imposing the rules (Gercama et al., 2020).

Climate change is having an enormous impact on reefs worldwide. Rising ocean surface temperatures induce coral bleaching, killing them or making them susceptible to diseases, and making collecting activities another insult added to the injury.

In South America, the equivalent impact of coral bleaching on reef fish populations are forest fires and open pit mining. Brazil lost over 5000 mi²/13,000 km² cover during the first seven months of 2020 and ca. 3,500 mi²/9,000 km² in 2019 (BBC News, August 28, 2020). The added impact of illegal gold mining, with heavy discharges of cyanide and mercurial compounds have irreversible effects on aquatic environments. Freshwater fish are an incredibly diverse group which, often as the result of movement restrictions within narrow bodies of water, have evolved a high degree of endemism and are commonly restricted to a single stretch of one river. This wonderful result of geological history is also quite often linked to their fate when these bodies of water are contaminated, making them highly vulnerable organisms (Olden et al. 2010).

Still, the global aquarium trade and the quest for sustainability is not only about the animals. Fish will benefit from most well-structured management programs. It is also about lending a hand to the impoverished communities that depend on these fish as their primary source of income. Until these communities are taken into account as stakeholders, not just as faceless suppliers of fish, but also as stewards of their valuable renewable natural resources, it will be difficult to make this industry sustainable. The main factor missing is supervised capacity building.

¿Why supervised? Because this industry has been doing its day-to-day work unchanged for such a long time that unless they receive guidance and supervision to do things differently, they will gravitate back to the old ways in no time (pers. obs.).

Looking at the problems along the value chain, from collector to final client, it is quite obvious where the shortcomings lie. Muyot et al. (2018) analyzed the added value of the trade, as fish change hands from reef to retailer. Aquarium trade fishermen often have low profit margins accompanied by very high mortality rates that are invariably compensated by–no surprise here–collecting more fish. On the county of origin side, exporters have the highest investment in facilities and equipment and require high net margins to cover the cost of their losses. Only a few of them have tried becoming more profitable by reducing their losses. Standard operating procedure is always “collect more fish” than will be ultimately shipped. With proper training, fishermen and middlemen could achieve much lower mortality rates with the same amount of work, thus increasing their net income. If mortality can be dropped from 80% to 20%, sales could be doubled (from 20% to over 40% of current catch) and the impact on wild populations could still be reduced by half of what it is now. In other words, with appropriate husbandry, fishermen could capture 50 instead of 100 fish and achieve the same bottom line. With 20% loss rates, they would still sell 40 instead of 20 to the exporter, and in much better shape than currently observed.

No business can be profitable in the long term, much less sustainable, with the current attrition numbers seen in the wild ornamental fish trade. Changing this will require training and constant supervision until new collecting and husbandry methods have become second nature.

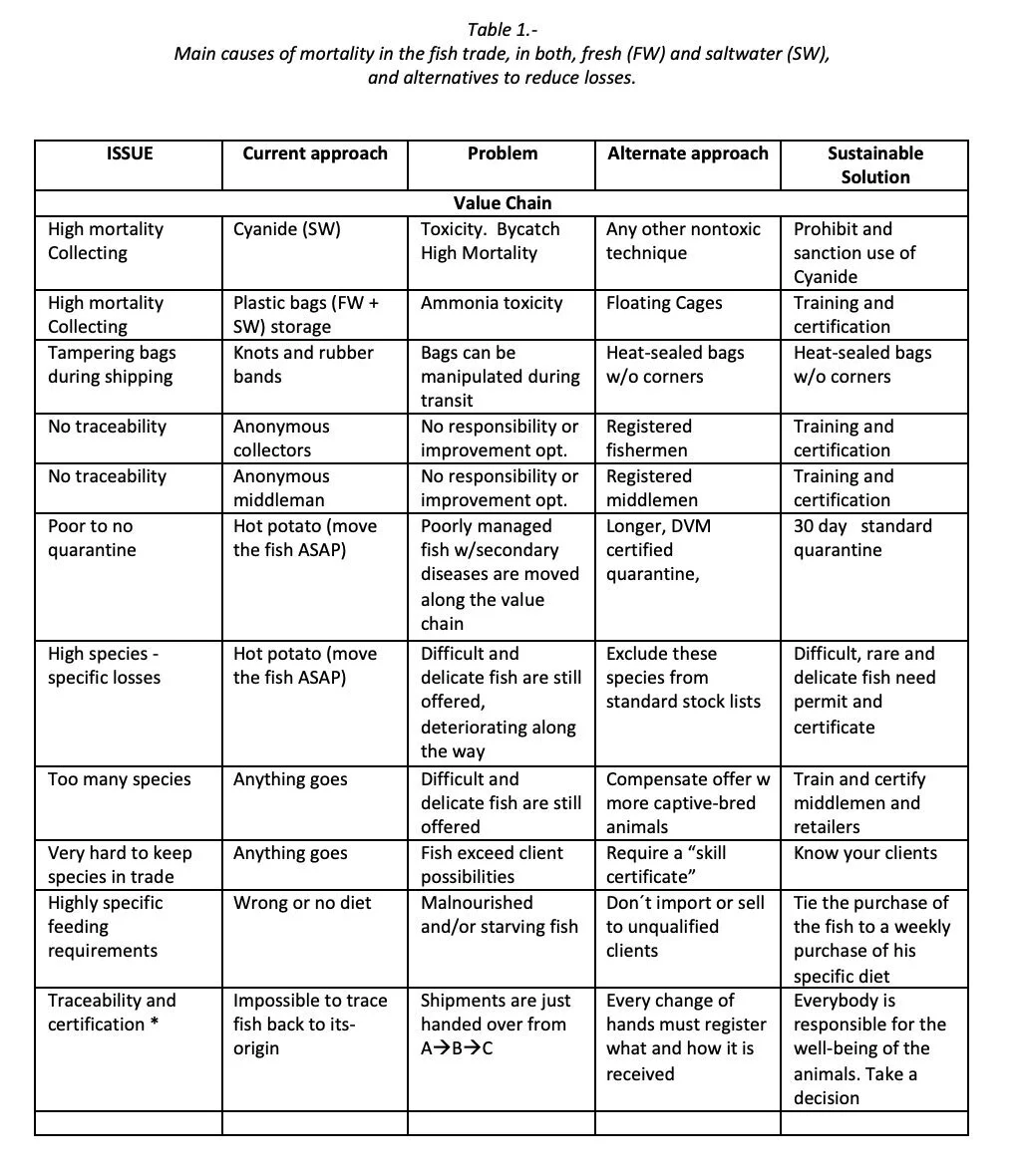

The proposals I include here to improve the sustainability of the global aquarium fish trade is based on the opportunity of reducing or eliminating common problems found in the commerce of freshwater and saltwater fish and invertebrates.

This system is meant to guarantee clients that, regardless of where they source wild-caught fish and invertebrates around the world, they have all undergone the same responsible control procedures from origin to final purchase. The certification of such process is focused on providing the fish the best possible care during every step of the way. For those hobbyists that have traveled abroad to collect fish, the idea of a global aquarium fish trade system is that animals should always be caught and transported with the same care and attention that every responsible hobbyist would employ if the fish in the cargo hold were his own.

A young silver arowana (Osteoglossum bicirrhosum) in one of the author’s research aquaria in Bogotá, Colombia. Most arowanas of all species are very fast growing and outgrow their enclosures in a year or less. In many cases they become unwelcome guests just after turning the other inhabitants of any community tank they’re housed in into three final meals. Potential hobbyist buyers should be made aware of this fact with large signs that display the minimum recommended size of an aquarium for this and similar sized species. Perhaps a photo showing the animal swallowing a large fish could illustrate exactly how voracious these species can be. Silver arowanas are an intelligent, spectacular and very desirable tropical freshwater fish species for advanced aquarists, but all potential customers must be clear what they are buying, just how much (to almost 4’/1.20 m) and how fast this species can grow after it leaves the store as a 5”/13 cm juvenile. Image: ©Peter Rockstroh 2021.

Collecting wild ornamental fish

The following are guidelines to avoid damaging collecting methods and improve holding conditions, whose combination will result in much higher survival rates of the catch:

Certification that no dangerous, toxic or high impact collecting techniques have been employed

No fish are to be captured using cyanide, or other toxic organic (Lozano Balcázar, 2005) or inorganic chemicals. Fish must look healthy and show no signs of intoxication. No unusual swimming movements. Eyes are clear and the animals are alert.

No fish are to be captured using fishhooks. No signs of external or internal damage. No habitat damaging nor degrading techniques can be employed to catch fish.

Proper handling is ensured to reduce mortality from collection point to export facility

Dangerous (for the fish) and environmentally damaging collecting techniques have to be eliminated. Optimal husbandry and feeding precede the best possible transport conditions, including a reduction of excessive shipping densities

Fishermen and middlemen must receive training and supervision to improve collecting techniques and temporary holding conditions, as well as implement selective fishing, to avoid retail stocks of (nearly) all hard to keep, extremely rare and endangered species. Training programs should be standardized, with specialized additional information for each locality.

The goal is assembling teams of certified, registered, licensed and trained fishermen who collect only approved and/or especially ordered species with non-damaging techniques. Fish should be held in properly designed ponds, net cages or large containers until ready for transport.

All fish are to be fed several times a day when necessary. Before sending the animals to a middleman, they must be inspected to verify health, behavior and quality and then prepared for transport. The animals are sent to middlemen or exporters with all pertaining documents. Everyone along the value chain must comply with the regulations to avoid that the next in line has to assume responsibilities for problems caused by previous links in the trade.

Improved handling is ensured to reduce mortality from exporter to retail vendor

Animals received in poor conditions should not continue in trade, period. In order to reduce losses, at first suspicion registered of a case of disease the animals should be separated and receive proper attention until fit for export. Poor to no traceability complicates the process of finding areas for improvement. All fish must be accompanied by proper documentation, including collector name/s, collecting site, date and middlemen data. Those lacking documentation should undergo immediate 30-day quarantine. The “hot potato” approach currently in place tends to reward quickly unloading problems on to the next participant in line along the value chain. Animals that do not pass inspection should not be moved until diagnosed, treated and recovered. Short to no quarantine in country of origin always equates to high losses in the final market. Flow of live fish and invertebrates should be documented from origin to final market and all require a minimum 30 day quarantine and health certificate issued and signed by a registered veterinarian to ensure they have no health issues and they are feeding normally, which should also prepare them for the long shipping time.

Formal holding ponds shown near Inirida in southeastern Colombia are probably the best practical solution to keep fish for an extended time before shipment to exporters. These ponds are fed with water from the river nearby as can be seen by the color. The system even has an overflow valve at the entrance, to avoid losing the stock should the river rise too rapidly. The ponds were built with a layer of geotextile and staked wooden walls to maintain structural integrity and shape in case of flooding. Image: ©P. Rockstroh, 2021.

A Global Transit Care System and what it should include

The main cause of death for all fish and invertebrates in transit is ammonia intoxication, wherein the animals die poisoned by their own metabolic waste. In other words, they spent too much time in a bag. As transit times increase, survival rates plummet.

Before any fish is placed in a bag for shipment, it should previously have been conditioned for transport. That means it is well nourished and has been feeding regularly up to 24-48 hours before being bagged. The animals should not show any signs of external damage, visible symptoms of illness, external parasites or abnormal behavior or movements. It takes a lot of work to achieve that level of normal.

Part of the aquarium trade chain, between fisherman to exporter, currently don’t always fulfil the requirements that condition fish for transport. Fish can be stressed, malnourished and beginning to show signs of secondary diseases. Many have not been fed for several days, and specialized feeders have not been fed at all since, “They won’t eat anyway”.

Under these conditions, they are placed in shipping bags at the highest density allowed for the size and species, closed and boxed. Under these conditions the risk of losing animals due to deteriorating shipping conditions is high. Stress accelerates their metabolism and asymptomatic carriers become symptomatic vectors and a six-hour delay with a connecting flight becomes a death sentence.

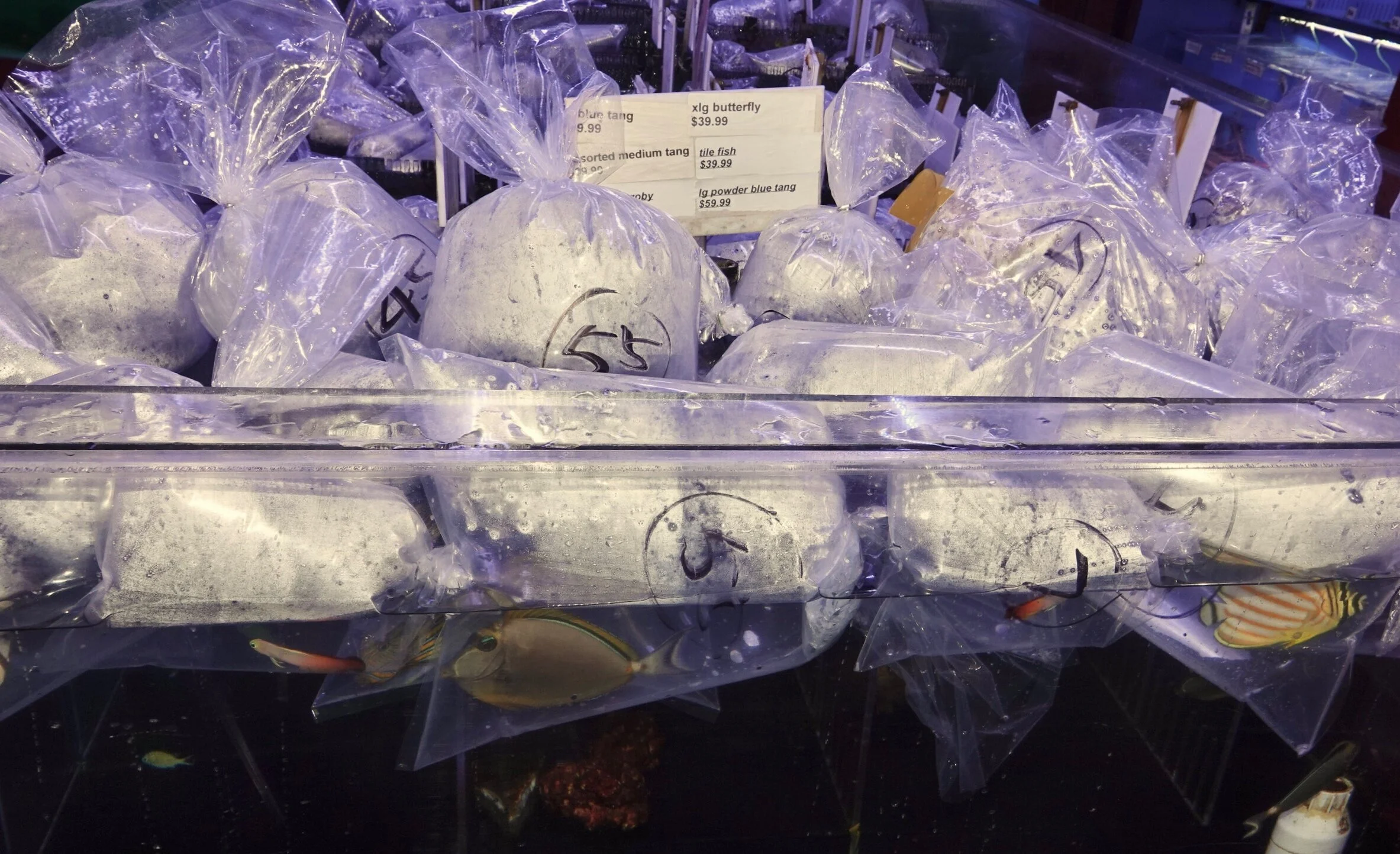

An assortment of bagged Philippine tropical reef fish floating in a holding tank, fresh out of the shipping cartons after an overnight flight from Asia to the U.S. west coast. Following a water change and fresh oxygen, these fish are being sold direct to retail customers at reduced prices by a dealer looking for immediate turnover. This is just one example showing the continued commoditization of wild-caught coral reef fish and is exactly the opposite of what is proposed here. Image: J. Vannini.

What can be controlled, avoided, or at least reduced to improve this situation?

The first step to help reduce losses during transport is controlling what goes into the bag, starting with fish densities. Many species are shipped in standard numbers, although they frequently report losses of, for example, 10%. If these losses are indeed consistent, it makes more sense to reduce the bags fish contents by at least 10% and try to consistently ship this species without losses. This, instead of incurring a regular loss of 10%, and on other occasions even more than that. Part of this is also choosing the right bag size and packaging concept.

The second step is selecting carefully who goes into the bag. It takes only one individual to trigger a chain reaction that can wipe out the whole bag. The shipper must be very critical of what he is shipping and how he conditioned the animals to prepare them for a long transit time.

The third step consists of adding a bar coded transit or tracking card to every bag that registers the origin of the fish and tracks it all the way from collection point to importer. Each change of hands registers date and time as well as water conditions (was there a water change and were chemicals added? what were the water parameters? etc.). This tool allows a very precise control of times the bags have been in transit, especially if coupled with clear indications of what to do when the animals in bags reach or exceed their (very real) expiry date.

The fourth step involves creating service teams at major stopover points along the main export routes. Their job consists of following a series of instructions issued by the shipper, who can authorize them to execute from a simple visual inspection of a shipment, to a complete change of bags and water, in case of delays or other problems. These procedures may not require a certified veterinarian, but at least an experienced team of people that routinely work with fish. It is very important to consider worst case scenarios, especially for big companies with large shipments, and structure an emergency team that can handle even the largest orders efficiently. These services are paid by the shipper. If there were other options this must be taken into account, but there is a time limit for fish in bags. Once they reach or exceed that limit, they don’t have many choices. They either undergo a change of water and hope for the best, or the shipper will lose the shipment.

Ideally there should be a designated room in the cargo area of major transit points with good illumination, an RO or other filtered water source, tables and sinks to work with, so shipments that need bag changes, can be processed rapidly with minimum risk for the animals. Basic water analysis should be conducted here as well. Any water changes must be registered on the tracking card.

The first and second steps are quite non-controversial and should make sense to most working in the industry. Yes, it opens up the doors to endless conversations about the relativity of 10% before and after, but truth be told, the frame of reference for this global approach is based on which decisions are best for the fish.

The third and fourth steps are suggestions based on available mortality numbers. Just ask any importer or large fish store owner how many boxes of live fish he has lost over time due to delays and other foul ups, at what cost, and how much he would have paid to be able to call “the guy” that could have changed the DOA for an IOU.

You can’t plan for every possible condition and contingency. You think you are prepared for anything, but you can’t prevent weather delays, bureaucracy, jungle engineering and rural holidays from happening. There will always be a predictable number of unpredictable events that will require assistance on the way.

Just adding a tracking card to every shipment is not enough. Unless the right actions are taken when complications arise fish will still be lost, except that now the cause will be evident from the information at hand. Of course, the contact person or team that will attend these in-transit emergencies must be trustworthy professionals, endorsed by the shipper. It should also be clear that their help is either approved in those cases where otherwise the animals would be lost, or will be lost during the rest of their remaining transit time, or by direct instruction from the shipper. Since these cards carry all the information, they can also be used to contact the emergency teams in advance, when unforeseen circumstances cause delays that put shipments at risk long before arrival at their final destination.

Keeping track of time

The most important aspect of a tracking card with notes is keeping an accurate record of time and water conditions, every time the fish change hands. Tracking cards should also have indications of maximum allowed bag times, and indications on how to proceed when they have been exceeded. That way these problems are not passed on, but a decision is taken based on the well-being of the fish. Tracking cards are the low-cost alternative to a data logger, to register the delays that caused the loss or perhaps other problems of the shipment. Normally, data loggers are only checked at destination where it could already be too late to correct a transit problem. A tracking card could have already triggered a response to avoid losing that shipment.

Travelling Business Class

The current methods for packing and transporting fish is the result of many decades of twitching and tweaking traditional methods, until settling for what it is now: Fish and invertebrates are placed in plastic bags that are filled with 20%-33% water and 67%-80% oxygen or air. The bags are wrapped in newspaper as isolation and placed in Styrofoam coolers that fit in cardboard boxes. For extended transit times in cold weather, boxes are fitted with heat packs to avoid lethal temperature drops. Bags and boxes are almost standard and all exporting countries have publications amd guidelines that indicate how many fish of a given species can be packed into a given size bag and how many bags per box. These boxes are plastic wrapped and fitted with a leak and spill-proof tray.

Fish transport bags come in different qualities, many of which should not be allowed for transport. As “green” as they may sound in theory, fish should NEVER be placed in a plastic bag including or made from recycled materials. The risk of rupture or puncture is too high. Bags carrying stingrays, catfish or any other species with spines or other defense mechanisms that can perforate the bag are often shipped in double bags with a plastic sheet inlay, to protect the bag from this type of accident.

In the 1950s the plastics industry developed the first metallocenes, a group of polymers with very high puncture, stretch and tear resistance, making them ideal for the transport of aquatic animals. A balanced formula with good optical properties, high mechanical resistance and excellent sealing properties would be a great standard polymer mix, specifically for this application. Some clients may complain about the big price difference between currently used bags and these alternatives. In a sense they are right, but they are not in the plastic bag business. When the cost of these bags is compared with cheaper standard bags, and added to the cost of fish, the difference is negligible. Including losses and risks, the price differential disappears.

Eventually a heat-sealed bag could substitute the knots and rubber bands still used today. Occasionally bags have been tampered with in transit. Heat sealed bags, if opened, have to be substituted. These bags can be manufactured in relatively short production runs on small film blowing units, and they can be identified by several methods. This allows the production of unique, tamper safe, custom bags.

Last but not least, bags for fish should never have corners. Shoaling fish, especially small tetras, tend to dart into corners when panicked. Occasionally their opercular spines get stuck and they die, starting to foul the water. To avoid that, corner less bags are preferred. These can be made manually, folding and taping the corners of each bag, or they can be cut to shape with a heat-sealing edge profile.

Travelling First Class

Companies that regularly move very large amounts of fish and supplies, preferably back and forth on the certain local routes, have long had the option of transporting fish in a tank with its own oxygen supply (IATA 2009). Just as there are specialized airfreight shipping containers for live Maine and rock lobsters or Dungeness crabs, live fish can be flown in a permanently oxygenated container, custom built to accommodate a cargo plane. The high cost of these containers is justified with much higher shipping densities and in Colombia, when used for domestic shipments, by sometimes using them to ship other perishable cargo items on their way back to isolated fishing communities.

Hopefully many wild aquarium fish source communities in rural areas around the world will be able to avail themselves of this option in the near future.

In the next article I will propose some conservation and improved management recommendations to benefit wild tropical fish populations.

In one of the workshops in the community of Caranacoa, eastern Colombia that is also shown below, attendants were divided into groups and asked to design a floating net cage to hold their catch for a week. One of the participants, who is deaf and mute, became visibly exasperated while watching his companion’s poor drawing skills and lack of perspective. As is shown in the image below left, he finally took away his friend’s marker and finished the drawing himself with a proper 3D render of how it should look, as is shown here. Image: ©Peter Rockstroh 2021.

During recent audiovisual workshops to improve live fish management that were conducted by the author in several small communities in southern and eastern Colombia it was an amazing experience to witness when participants fully understand, many of them for the first time, what ultimately happens with the tropical freshwater fish they catch. Some of the clips I used showing aquascaping competitions or breeding installations abroad had to be shown several times to the audience, who was fascinated. One of the attendants, an older fisherman and also an Evangelical pastor, saw a beautiful display aquarium on screen and concluded that his fish had, “…passed on to a better life.” Images: ©Peter Rockstroh 2021.

References Cited

Ajiaco-Martinez R.E, Ramírez Gil, Hernando Sánchez-Duarte, Paula Lasso, Carlos A. Trujillo & C. Fernando. 2012. Diagnóstico de la pesca ornamental en Colombia. HUMBOLDT, 2012. 152 pp.

Dabney, K. P., Robert H. Tai, J. T. Almarode, J. L. Miller Friedmann, G. Sonnert, P. M. Sadler & Z. Hazari. 2011. Out-of-School Time Science Activities and Their Association with Career Interest in STEM, International Journal of Science Education, Part B, DOI:10.1080/21548455.2011.629455

FAO Colombia. 2019. Perfíles de Pesca y Acuicultura por Países. Hojas de datos de perfiles de los países. In: Departamento de Pesca y Acuicultura de la FAO [en línea]. Roma. Actualizado 1 noviembre 2003. [Citado 20 October 2020]. http://www.fao.org/fishery

Gercama, I., N. Bertrams & N. Lambongan. 2020. ‘After the coral ban I lost everything’. BBC News, Feb. 27, 2020.

Green, A., I. Chollett, A. Suárez, C. Dahlgren, S. Cruz, C. Zepeda, J. Andino, J. Robinson, M. McField, S. Fulton, A. Giro, H. Reyes & J. Bezaury. 2017. Biophysical Principles for Designing a Network of Replenishment Zones for the Mesoamerican Reef System. http://www.healthyreefs.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Biophysical-design-principles-for-the-MAR-2017.pdf

Huntley, R. & R. Langton (eds.) 1994. Captive Breeding Guidelines. Aquatic Conservation Network Canada.62 pp.

IATA. 2009. Live Animal Regulations 2009. General Container Requirements for Aquatics (CR51-60)

Kessler, R. 2013. New Initiatives to Clean Up the Global Aquarium Trade. https://e360.yale.edu/features/new_initiatives_to_clean_up_the_global_aquarium_trade

Khutor, Rosa. 2016. CITES. Traceability: Technical Standards. SC70 Inf. 32 bis

Lozano Balcázar, A. 2005. Los barbascos utilizados por los Ticuna en el Parque Nacional Amacayacu. Trabajo de Grado para optar al título de Biólogo. Universidad de los Andes

Mancera Rodríguez, N.J., et al. 2008. COMERCIO DE PECES ORNAMENTALES EN COLOMBIA. Acta biol. Colomb., Vol. 13 No. 1, 2008 23 - 52

Murray, J.M. & G. J. Watson. 2014. A Critical Assessment of Marine Aquarist Biodiversity Data and Commercial Aquaculture: Identifying Gaps in Culture Initiatives to Inform Local Fisheries Managers. PLoS ONE 9(9): e105982. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105982

Mundy, V. and G. Sant. 2015. Traceability systems in the CITES context: A review of experiences, best practices and lessons learned for the traceability of commodities of CITES listed shark species. TRAFFIC report for the CITES Secretariat. 89 pp.

Muyot, F. B. et al. 2018. Value Chain Analysis of Marine Ornamental Fish Industry in the Philippines. The Philippine Journal of Fisheries 25(2): 57-74

Olden, J.D., M. J. Kennard, F. Leprieur, P. A. Tedesco, K. O. Winemiller and E.Garcıa-Berthous. 2010. Conservation biogeography of freshwater fishes: recent progress and future challenges. Diversity and Distributions (2010) 16; 496–513

Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). 2020. Fisheries Situation Report. Jan-Dec 2019.

Trager, R. 2017. Sensing illegal cyanide fishing. https://www.chemistryworld.com/news/thiocyanate-detector-aims-to-end-illegal-cyanide-fishing/3007092.article

Van Beijnen, J. & G. Yan. 2020. Culturing marine ornamentals: a $5 billion opportunity https://thefishsite.com/articles/culturing-marine-ornamentals-a-5-billion-opportunity

Young, M., S. Foal and D. Bellwood. 2016. Why do fishers fish? A cross-cultural examination of the motivations for fishing. Marine Policy 66 (2016) 114–123

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC® 2021-2025 ©Peter Rockstroh 2021, ©David Bono 2021 and Steve Childs 2006.

Follow us on: