Anthurium diabloense: What’s in a Name?

Of pirates, plants, and patience

by Jay Vannini

The Devil was in the details

Anthurium diabloense Vannini, Croat & Castillo Mont is an eye-catching, recently published (September 2022), and narrowly endemic Guatemalan and Belizean rainforest aroid that is amenable to container culture and likely to be of interest to ornamental horticulture.

It also has an interesting if somewhat convoluted backstory.

At a time when botanists name unusual tropical plants after fictional characters from “Star Wars” (Begonia darthvaderiana C. W. Lin & C. I Ping), Tolkien’s “The Hobbit” (Dracula smaug Baquero & Meyer), and even pop stars (Gaga germanotta F. W. Li & Windham), perhaps it’s worth exploring the origin of this new scientific name.

Several people I know who were familiar with the proposed binomial prior to its formal publication remarked that after looking at Anthurium diabloense they assumed that the specific epithet alludes to the narrow, upswept basal lobes that resemble horns or bat wings and definitely impart a “devilish” aspect to the leaves. This association is, however, quite coincidental since the name is, in fact, based on the type locality for the species, which is situated directly adjacent to Los Cayos del Diablo (The Devil’s Cays) on Guatemala’s Caribbean coast. Hence the Latin suffix -ense = native of, or relating to, a particular place.

And how did Los Cayos del Diablo get their name?

While I lived in the hot and rain-soaked boonies outside of Puerto Barrios in the Izabal Department in the mid-1970s and based on local hearsay, I always understood that Los Cayos del Diablo derived their name from superstitions about malign, other-world forces having once inhabited these two picturesque, forest-covered karst outcrops.

Later research showed that the truth is likely far more interesting than just another folktale about one of Satan’s favorite Caribbean vacation spots.

Gulf of Honduras pirates, the Spanish colonial ports of eastern Guatemala and Los Cayos del Diablo

During the late 16th and 17th centuries, the Caribbean coasts of southern México, Central America and northern South America were plagued by maritime piracy that prospered through attacks on the valuable commercial trade between the Spanish Crown and its New World colonies. The Gulf of Honduras, which includes the coastal waters of Belize, Guatemala, and Honduras, saw plenty of action by well-known British, French, Dutch, Miskito, and Antillean pirates and smugglers (Floyd, 1967; Cabezas Carcache, 1994; Marley, 2010). The coastal area around what is now Omoa, located on the Guatemalan-Honduran border, was a well-known haven for freebooters at the time.

Due to constant predatory raids on colonial exports by pirates at the Bodegas del Golfo on the south shore of Guatemala’s Lago de Izabal, in 1644 Fuerte (Fort) Bustamante was built on a choke point on the Río Dulce to guard access to the Crown’s ports located further west on the lake (Cabezas Carcache, 1994; Anon., 2018). This Spanish military outpost was later expanded and renamed the Castillo de San Felipe de Lara.

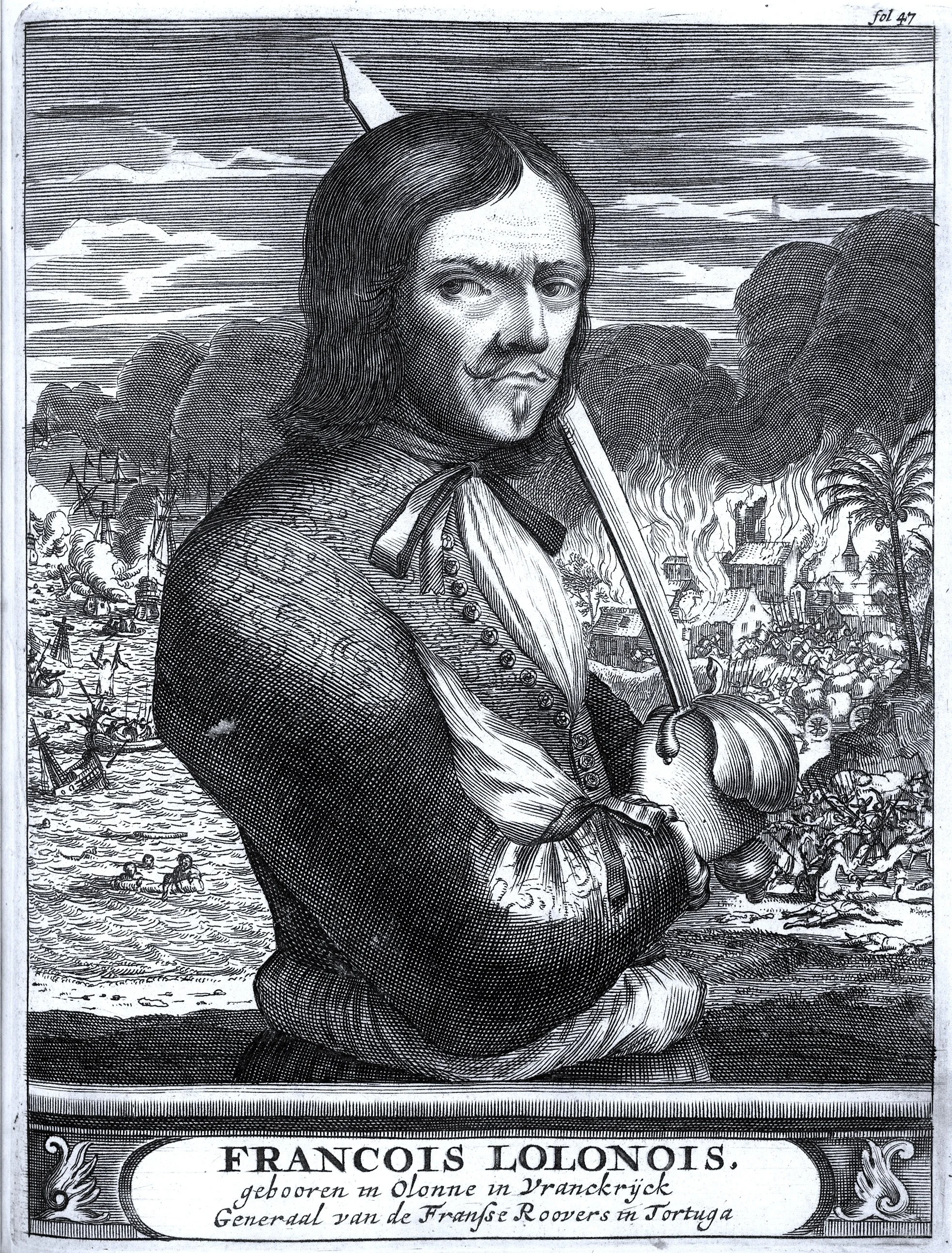

A far cry from Captain Jack Sparrow, Jean David-Nau/François l’Olonnais depicted with some of his handiwork in the background in an illustration for Alexandre Exquemilin’s classic account of 17th century Caribbean pirates. Translated to English his nicknames included, “The scourge of the Spaniards”, “The Devil’s envoy”, and “The one from Olonne”. While success in cruel and corrupt professions such as piracy, human trafficking, the narcotics trade, and politics demand cruel and corrupt individuals, this young man was considered exceptionally wicked even among his malevolent contemporaries. Image: Commons from Esquemelin 1678.

During what has been called “The Golden Age of Piracy” (~1650-1730), in mid-1667 the infamous French pirate Jean-David Nau, better known as François l’Olonnais and alternately nicknamed, “Le fléau de Espagnols”, “El enviado del Diablo”, or simply, “El Olonés” (Cabezas Carcache, 1994; Anon., 2018) found his fleet becalmed in the Gulf of Honduras while bound for Nicaragua. The vessels were unable to remain together due to strong tidal forces. Because of this, some ended cast up on the northwest coast of Honduras. From a base on a river nearby l’Ollonais went on to first attack Puerto de Caballos (now Puerto Cortés). After finding it mostly deserted and having little of value to plunder, and then casually murdering its few residents, his march inland from there to assault San Pedro Sula ended in a disastrous defeat at the hands of its Spanish and Criollo defenders. This humiliating and costly loss led to a series of further misfortunes that culminated in his gruesome death in 1668 at the age of 38 (Esquemelin, 1678).

Drifting west into the Bahía de Amatique, he sent his sailing canoes to monitor Río Dulce for arrivals and departures of Spanish trade ships, while the rest of the fleet moved further south towards the Guatemalan mainland.

It is reported that l’Ollonais used two coastal islets immediately adjacent to the port of Santo Tomás de Castilla in Izabal Department as a temporary refuge to repair his vessels and to plan a new campaign. Their sheltered position and plentiful fresh water sources nearby would have been key attractions. His accidental arrival followed an attack by other raiders on Santo Tomás in 1665 that forced an evacuation of the port’s residents to a more secure position at Fuerte Bustamante located some 25 miles/40 kilometers airline to the west. This left the Bahía de Amatique waters completely unprotected and these pirates free to roam around the area terrorizing small coastal Q’eqchi’ Maya and Afro-Carib settlements while they debated their next major raid, which would turn out to be a frustrated and ill-considered plot to attack the rich and well-defended settlement of Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala (now known as Antigua Guatemala), located in the central highlands (Ruiz Gil & Morales Padrón, 2005; Marley, 2010; Anon., 2018).

Despite l’Olonnais’ entreaties, his captains and crew ultimately decided against such a risky enterprise and his fleet split, with a key group departing to Tortuga in large sailing canoes by way of Costa Rica. Stymied in his plot to plunder Guatemala’s capital city and his flagship too large to move easily in shallow waters, he remained trapped and short of provisions in the southern Gulf of Honduras for several months (Esquemelin, 1678).

François l’Olonnais’ reputation for depravity and the horrendous techniques that he employed for torturing and slaughtering captives were such common knowledge on the Spanish Main that–according to a survivor’s account–when he was finally captured by a native Guna defensive party in what is today the Darién Province of Panamá, the natives cut him apart while still living, then threw his body parts into the fire to roast and eat them so, “…that no trace or memory might remain of such an infamous, inhuman creature.” (Exquemelin, 1678; Ruiz Gil & Morales Padrón, 2005).

Bahía de Amatique in the southern Gulf of Honduras showing Los Cayos del Diablo lower left. François l’Ollonais’ extended presence in 1667 in the area shown is very well-documented by historians but evidence of his anchorage at Los Cayos del Diablo is largely based on oral accounts dating from the mid-19th century. Image: ©J. Vannini 2022.

So, while the Diablo in Anthurium diabloense refers to the type locality being immediately opposite Los Cayos del Diablo, it now seems almost certain that the Diablo in Los Cayos del Diablo refers to the “Devil’s envoy” himself, the rapacious and sadistic pirate François l’Olonnais.

Los Cayos del Diablo shown left of center in front of lightly-disturbed coastal rainforest seen from near Santo Tomás de Castilla. Image: ©K. Kühne 2023.

The plant

Anthurium diabloense is one of the smaller members of section Andiphilum Schott–resurrected in Croat & Hormell, 2017–that includes all north Mesoamerican Anthurium species formerly placed in sections Cardiolonchium, Belolonchium, and Schizoplacium. Species in this section are mostly terrestrial or lithophytic, have orange to bright red ripe large-seeded berries with a pasty mesocarp, terete to broadly sulcate petioles, moderately coriaceous leaves, and persistent cataphylls. Section Andiphilum is shown as a well-supported major clade in a recent molecular phylogeny of Anthurium (Carlsen & Croat, 2019). Adding recently published taxa, several that are currently being described and others known by me to be undescribed, this section currently includes well over 50 species. Plants assigned to this section range from southern México in Puebla state to western Honduras on Gulf of Mexico, Caribbean, and Pacific drainages.

Part of the Contreras specimen set of Anthurium diabloense collected in 1966 and deposited at University of Texas Austin (LL) and Missouri Botanical Garden (MO) herbaria. Image: ©Missouri Botanical Garden.

Because of major shortcoming in published studies on regional flora until recently, among others Anthurium diabloense has been misidentified as A. seleri in the past. For one example see the Esteban Martínez accession #23592 from 1988 made very near the type locality, which appears to be the first collection made there by a botanist.

Two Guatemalan and Chiapan Anthurium species–A. aff. lucens and A. verapazense–have also been confused with A. diabloense by local researchers (Aragón, 2003; pers. obs.) as well as with each other (e.g., Díaz, 2021). Clearly, a lot more work is required to clarify the taxonomic relationships among northern Mesoamerican Anthuriums (Hodel & Moya López, 2022; Croat, pers. comm.; pers. obs.).

An image shown in Graf (1980) and identified as A. berriozabalense notes that it is from Guatemala and a, “…glaucous plant with hard, sagittate leaves odd because the long basal lobes are curiously crossed.”. Graf’s image shows what appears to be a severely stressed plant in cultivation. His comments aside, occasional newly emergent leaves on plants in this species will have misshapen basal lobes, especially those surviving in recently disturbed areas.

As far as I have been able to determine, the earliest documented collection of Anthurium diabloense, then assigned to A. berriozabalense, was made directly on the border between southeastern Petén and northwestern Izabal Departments and southwestern Belize in 1966 by Elias Contreras for noted U.S. botanist and expert on Mayan Region flora, Cyrus Lundell.

Anthurium diabloense was described from an area known for its exceptionally rich floral diversity and local endemism, and many other Anthuriums occur alongside it in coastal forests or at higher elevations on adjacent Cerro San Gil. These include A. bakeri, A. castillomontii, A. cubense, A. flexile, A. gracile, A. huixtlense, A. interruptum, A. lancetillense, A. aff. lucens, A. obtusum, A. pentaphyllum, A. schlechtendalii, and A. verapazense.

Anthurium lancetillense in nature at low elevation on Cerro San Gil, Izabal where it occurs sympatrically with A. diabloense. Image: ©J. Vannini 2022.

A sunlit landscape of Cayos del Diablo photographed by Guatemalan sport diver Karin Briere in 2019 from the shallows between the old hotel and the islets. Image: ©K. Briere 2022.

A young, artificially propagated Anthurium diabloense flowering in California in a 6"/15 cm basket. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2022.

Another mature Anthurium diabloense with good leaf form shown in nature near the type locality west of Santo Tomás de Castilla, Izabal Department, Guatemala. Image: ©K. Kühne 2023.

Drought stressed Anthurium diabloense growing through leaf litter on exposed karst near the type locality in June 2024. The severe drought that impacted the rain- and cloud forests of the Caribbean slope of Central America and western Colombia during 2023-24 had visible impacts on regional aroid populations. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

A group of four year-old, second generation, artificially propagated Anthurium diabloense cultivated as patio plants in a private collection in Guatemala's tropical lowlands. Image: Jay Vannini 2024.

To continue reading the rest of this and other Premium Content articles, please subscribe to Esotérica Exclusiva.

Access to deeper dives and behind the scenes looks into advanced tropical horticultural practices as well as observations on fieldwork, plant collection management, and Neotropical wildlife.

Follow us on: