A Hoot of a Spectacle

Captive breeding and radio-tracking Spectacled Owls

By Jay Vannini

A pair of mature Spectacled Owls (subsp. chapmani) in the Reserva Bellavista, Victoria, Caldas Department, Colombia. Image: ©Juan José Arango 2022.

Among the many colorful and iconic New World tropical birds that make occasional splashy appearances in mainstream news, wildlife conservation fund-raising pleas, and internet videos, Spectacled Owls (Pulsatrix perspicillata) rank high in popularity due to their attractive appearances both as juveniles and adults. For northern birders who visit Central and South America to work on their life lists, this is a “must-see” avian species. Due to their distinctive suite of vocalizations, where Spectacled Owls do occur and guides are available they are readily located and easily observed on night walks.

Mature Band-bellied Owl, Pulsatrix m. melanota, shown perched under canopy in intermediate elevation wet forest, Pueblo Viejo, Mocoa, Putumayo Department, Colombia. Image: ©David Monroy Rengifo 2021.

The species is known to range from southeastern México–on all drainages throughout–more or less continuously to western Bolivia, northeastern Paraguay and northern Argentina. The genus contains two other closely-related, extant species in South America, the Band-bellied Owl (Pulsatrix melanota), native to middle elevation Andean forests from central Colombia through to central Bolivia, and the Tawny-browed Owl (P. koeniswaldiana) from the Atlantic forests of southeastern Brazil, adjacent Paraguay and Argentina. All three Pulsatrix species share pale eyebrow markings and “beards” that frame their dark facial disks, together with reverse-pattern juvenile plumages.

There are six recognized subspecies, mostly differentiated by rather minor color and size variations. The three discussed here are:

Pulsatrix perspicillata chapmani – ranges from southern Costa Rica to northern Ecuador on both Amazonian and Pacific drainages. Based on average measurements, this is the smallest recognized subspecies. The images of wild birds taken in nature in Colombia that are included here show this subspecies.

Pulsatrix perspicillata saturata – ranges from Veracruz and Oaxaca states of southeastern México through to Guanacaste Province, northern Costa Rica on the Pacific slope, and Limón Province on the Caribbean. Northern Mesoamerican Spectacled Owls usually show distinct barring on the pale belly feathers of mature examples. The Guatemalan birds I worked with in the field and captivity that are shown below are of this subspecies.

Pulsatrix p. perspicillata – ranges from the Venezuelan lowlands south and southwest throughout the Amazon basin to eastern Ecuador and Perú and central Brazil. This is the most widely distributed subspecies and appears to be the one currently exhibited in most zoos and animal parks around the world. All images I have seen of captive birds shown on the internet appear to be of this subspecies. A photo of a wild adult shown in nature in Amazonian Perú is included below.

These owls are usually found in the lowlands wherever they occur, but do range to at least as high as ~5,700’/1,750 masl in western El Salvador (Pérez-León et al., 2017). The highest elevation I have observed this species at was a close daytime approach of a curious, two year-old immature bird in a cloud forest relic near Tactic, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala at ~4,900’/1,500 masl.

California Great Horned Owl, Bubo virginianus pacificus, sheltering from the rain in a suburban environment in San Mateo County, California. Exceptional female Great Horned Owls from boreal forest are likely the heaviest New World owls and among the hemisphere’s most redoubtable avian predators. The geographic range of this species extends the length of both North and South America. Besides their normal rodent, rabbit and hare prey, they are known to kill animals as large as Greater Sage-Grouse and Wild Turkeys, different fox species, adult raccoons, and even domestic cats and bobcats (pers. obs.). Great Horned Owls will also readily prey on other raptor species when opportunities arise, and this may explain why Spectacled Owls are largely absent from areas where they would be expected to occur in suitable habitat in the Neotropics. Great Horned Owls are extremely defensive when on active nests and, generally speaking, will not hesitate to attack human intruders - occasionally resulting in severe injuries to unwary observers. Notice the sizeable hooks on the fellow shown above. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2022.

Spectacleds are large and very long-lived (to 35 years in captivity) for a Neotropical owl species, with only southern Great Horned Owls (Bubo virginianus, several subspecies) exceeding them in overall length, weight and longevity. While these two species are generally allopatric and almost invariably inhabit different ecosystems across their ranges, they do overlap in cloud forest habitat in at least one area in central Guatemala (pers. obs.) and likely do so elsewhere in southern México, Central and northwestern South America. In rare instances, they also breed in habitats suitable for Spectacled Owls in the eastern Colombian lowlands and beyond (P. Rockstroh, pers. comm.).

The largest Spectacled Owls, believed to be some Brazilian females, measure ~18-20”/45-50 cm overall and can weigh as much as 2.75 lb/1.25 kg. Mexican and northern Central American females can weigh up to 2.40 lb/1.09 kg, while females in other populations tend to max out at ~2 lb/950 gm. Captive-bred or -raised females in Guatemala approached the upper end of the weight range for the species, likely due to steady, high calorie diets as nestlings (pers. obs.).

Etymology: The genus name Pulsatrix almost certainly alludes to one of the owl’s calls, a throbbing or hammering/beating sound (from the Latin pulsatio, with a feminine termination). The specific epithet perspicillata is Latin for “conspicuous”, which this species certainly is. A rough translation that fits this owl’s description well would be, “The conspicuous one that hammers”.

Throughout much of their range they are known as Búhos de Anteojos, Tecolotes de Anteojos, and Lechuzones de Anteojos, which are all direct translations of their English common name. In Amazonian Perú they are also known as atauleros (= coffin-makers), which derives from two of their most frequently heard vocalizations; one that is a tapping sound as if a carpenter were hammering wood, and the other a throaty “whup-whup-whup-whup-WHUP-WOOP-whup-whup-whup” that is reminiscent of the sound a hand saw makes when being shaken to clear the blade of debris (Lindholm, 2000; W. Lamar, pers. comm.).

A recording of this type of call is embedded below.

Other than the better-known calls, sharp screeches are often made by large nestlings and even fully-fledged immature birds when hungry or lonely. In Perú, one immature bird was observed calling repeatedly at night by Bill Lamar, with the single long, rasping note described by him as “haunting”. As is the case for many other owls, disturbed nestlings will hiss. Less commonly a single, often loud and somewhat musical call is made by adult females, presumably when searching for their mates (pers. obs.).

Immature plumage patterns of Spectacled Owls throughout their range are mostly white and fawn (see images of captive birds below). The last body parts to color up after a final molt to mature plumage are on the birds’ heads. Despite the data derived from zoo captives, in nature the speed of the molt sequence likely varies among individuals, populations, and subspecies. Scattered ventral barring in captive examples of subspecies saturata was observed to intensify with age. Some examples from the Caribbean lowlands of Guatemala and Honduras are especially dark and vividly barred on their ventral surfaces (see images of wild Honduran individuals posted online; pers. obs.).

Flash photos usually exhibit bright yellow eyes in this species, while individuals photographed with natural light often show vivid orange irises. Changing light conditions will result in remarkable variation in iris colors in Spectacled Owls.

Facial detail of a young, sexually mature captive Spectacled Owl (subsp. saturata) at Finca El Faro. Image transferred from 35 mm slide: ©William W. Lamar 2022.

Adult female Verreaux’s Eagle-Owl (Bubo lacteus) ghosting about in gallery forest near Moremi, northern Botswana in 2007. This is another large tropical owl species prized by zoos and private raptor collections as an exhibit animal. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2022.

Spectacled Owls have been exhibited in European and U.S. zoos since at least the early 20th century (Lindholm, 2000). Together with the African Verreaux’s Eagle-Owl (Bubo lacteus) and Northern White-Faced Owl (Ptilopsis leucotis), this species is among the very few tropical owls likely to be seen in captivity outside of their countries of origin. Spectacleds are far and away the most popular of these three. Because of their high display value, tractability, and ease of maintenance, many zoos, aquaria, and animal theme parks around the world have captive-bred Spectacled Owls in their collections. Trained birds are considered good “Ambassador” avian species to educate the public on the importance of conserving Neotropical rainforests (Lindholm, 2000; The Peregrine Fund, 2022).

Due to their attractive appearance, at least until recently Spectacled Owls were still trafficked–although presumably on a limited scale due to their relative scarcity–in the illicit wild bird trade across their range states (Marín-Gómez et al., 2017; Pérez-León et al., 2017; pers. obs.). Despite this and other threats wild birds face, they are known to be tolerant of habitat modification, are reported from urban/suburban areas in Panamá and Colombia, and are currently considered a Species of Least Concern by the IUCN (Marín-Gómez et al., 2017; The Peregrine Fund, 2022; pers. obs.).

They were first bred in captivity at London Zoo in 1969 and remain popular with British zoos to this day (zooinstitutes.com, 2022). The first U.S. breeding was at Oklahoma City Zoo, which then held an excellent collection of unusual Neotropical raptor species, in 1978 (Lindholm, 2000). The first captive breeding reported from Latin America was in my Guatemalan collection at El Faro in the late 1980s (Vannini & Morales Cajas, 1989), followed by one at a bird park In Costa Rica and another at a municipal zoo in Brazil in 1994 (Lindholm, 2000).

One half of a resident breeding pair of Spectacled Owls (subsp. chapmani) snoozing high in the canopy of a tree in a 37 acre/15 ha. regenerating secondary forest fragment surrounded by urban development in Quindío Department, Colombia. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Other than a handful of wild-collected birds imported from Guyana and Panamá in the 1970s and 1980s, all captive Spectacled Owls in the U.S. and the EU appear to have descended from a few imports made several decades back from Surinam and Amazonian Perú-based wildlife dealers (N. Gale, pers. comm; W. Lamar, pers. comm.; Lindholm, 2000). The uniformity of the appearances of captive birds shown in contemporary images taken in zoos around the world supports this view (zooinstitutes, 2022), and there is concern that the captive population is likely inbred at this time.

A mature Spectacled Owl of the nominate subspecies in lowland Upper Amazonian rainforest, Maynas Province, Loreto region, Perú. This is the subspecies that was exported in numbers for the wildlife trade from Iquitos in the 1970s. ©Matt and Kaysea Bruce 2022.

In Guatemala they are distributed in forested areas along both slopes in lowland, foothill, and lower montane ecosystems. Extant populations on the Pacific side are known from the Tarrales Nature Reserve on the south slope of Volcán Atitlán, ~30 miles/48 km east-southeast from Finca El Faro but likely occur elsewhere along the volcanic piedmont in suitable habitat (Land, 1970; Howell & Webb, 1995; Eisermann & Avedaño, 2015).

Shown above, adult female and nestling South American Great Horned Owl, Bubo virginianus nacurutu, shown by day at a stick nest constructed in the crown of a Yagua Palm, Attalea butyracea. Horned Owls nesting in the tropical lowlands suggests that some competition with Spectacled Owls may occur where they are sympatric due to overlap of prey species. These photos were taken in an open, flooded llanos ecosystem near Paz de Ariporo in Colombia’s Casanare Department. Images: ©Peter Rockstroh 2022.

Cuddly appearance notwithstanding, Spectacled owls are formidable and opportunistic predators that are known to feed on a wide variety of surprisingly large vertebrates. They have extremely powerful feet and long, very sharp talons. Recorded prey items begin modestly enough and include large moths, beetles, land crabs, frogs, snakes, and even young Green Iguanas (Filipiak et al., 2012; pers. obs.). Moving up the evolutionary ladder, besides small to medium-sized birds such as motmots (Momotus sp.) and doves (Leptotila sp.), they are also capable of dispatching small and medium-sized mammals such as a variety of large rats and bats, marmosets (Callithrichidae), and small opossums (Didelphidae) (Gómez de Silva et al., 1997). Larger prey that have been cited in the literature include agoutis (Dasyprocta spp.), hog-nosed skunks (Conepatus spp.), and–based on an analysis of physical evidence–three-toed sloths (Bradypus variegatus), In my opinion, it is also possible that a vagrant Great Horned Owl made the radio-collared sloth kill reported in Vorin et al. (2009). Great Horned Owls, even the smaller forms that occur in the American tropics such as subsp. mesembrinus, are well-known for successfully tackling outsized and potentially dangerous prey items (see comments above). While reports of Great Horned Owls in Panamá are few and retrospective and it is now considered endangered in the country, it is documented to occur there (Olson, 1997; Jiménez-Ruíz et al., 2017).

Not a Muppet! A foraging adult Spectacled Owl (subsp. chapmani) is shown perched on a Coconut Palm (Cocos nucifera) frond on the beach near Tayrona National Park, Santa Marta, Magdalena Department, Colombia. Image: ©Peter Rockstroh 2022.

Spectacled Owls often hunt low in the understory (pers. obs), alongside streams, rivers and in mangrove ecosystems, as well as in mid-canopy in both low and intermediate elevation tropical forests. I suspect they fish when conditions permit. They have been found close to beaches in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Colombia (Land 1970; Pérez-León et al., 2017; P. Rockstroh, pers. comm.).

Like other large owls, juvenile Spectacleds can have a long dependency period where they often hang around their parents hoping for a feed. According to most published reports and my own observations, they take up to three years to complete the change from juvenile to adult plumage. Once fully fledged, the captive bred birds released at El Faro were often located via telemetry perched during the day on branches of Trumpet Trees (Cecropia peltata), immediately alongside the pale trunks where their juvenile plumage provided very effective camouflage.

In the 1980s I established a captive breeding project on the Pacific slope of Volcán Santa María at Finca El Faro, El Palmar, Quetzaltenango Department. Among many other vertebrate species that I worked with there under near-natural conditions, I had several mature Spectacled Owls that I had rescued from the local illicit animal trade years earlier. Prior to managing these individual birds, I had made observations of them in nature in Guatemala and Panamá, and had also rehabilitated another abused captive Spectacled Owl in the mid-1970s that had been caught while raiding a chicken run and briefly consigned to a miserable existence in a Guatemala City produce market housed in a parakeet cage.

The location and ecosystems at and adjacent to Finca El Faro are discussed in a paper on the diurnal raptor community there that is available as an open access article online (Vannini, 1989).

Carlos Moya, my long-time friend and indefatigable project manager shown at the entrance to the captive wildlife breeding project at Finca El Faro in 1988. Image transferred from 35 mm slide: ©Jay Vannini 2022.

The images shown below speak for themselves. These attractive owls bred successfully on a couple of occasions at El Faro and we later developed a reintroduction protocol based on my previous experience in falconry with training and hacking-back other raptor species in the U.S. and Guatemala. The two fledglings shown here were provided with supplemental food at their hack box (both lab rat pups and wild-trapped native rodents) following their controlled release and monitored via radio telemetry and visual observations through until full independence. To avoid the need to recapture the owls and the stress that involved, the leg-mounted transmitters were attached to leather aylmeri-type jesse anklets that were designed to fall off within six to nine months. The adults were also released at this site at a later date when I closed the project and moved on.

Mature female Spectacled Owl (subsp. saturata) and its newly fledged captive-bred offspring in an aviary at Finca El Faro, Quetzaltenango, Guatemala in 1989. Image transferred from 35 mm slide: ©Jay Vannini 2022.

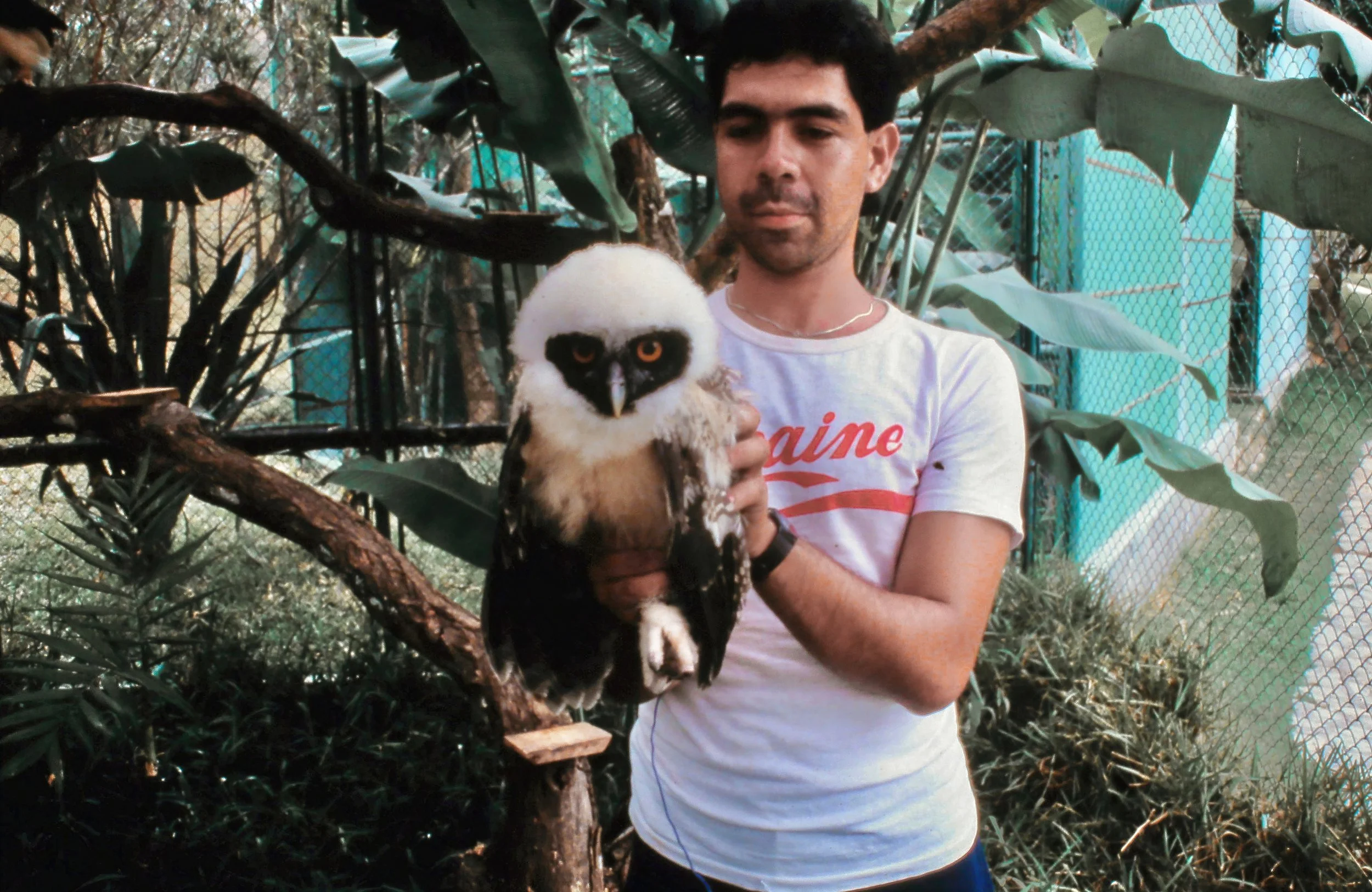

My field assistant at the time, Carlos Morales Cajas, is shown holding a fledgling captive-bred Spectacled Owl fitted with a dummy coated wire attached to a leather anklet. These wires were used essentially as chew toy surrogates to accustom the birds to the much more expensive (and much more fragile!) short whip antennas of the radio transmitters they wore on their legs when released. Several adjacent aviaries that housed other small and medium sized raptor and cracid species are visible in the background. Image transferred from 35 mm slide: ©Jay Vannini 2022.

A paper containing detailed information on the owls’ care, housing, breeding, description of the release site and its diverse and abundant prey base, radio telemetry results, field observations following fledging, etc. was published in an annual report that the Peregrine Fund issued in 1989 to their Maya Project donors, interested raptor researchers, and the local conservation authorities (Vannini & Morales Cajas, 1989). As time permits, I will make an effort to retrieve my now long-buried copies of both this “gray” publication as well as field notes to augment information contained here and “top-up” this article when convenient.

Shown above: Spectacled Owl fledglings shown at hack in riparian forest at the release site in premontane wet forest, Finca El Faro. One owl’s head is just visible on the right inside the elevated hack box while another sits on the ledge the birds used to feed and familiarize themselves with the immediate area before they made their initial short exploratory flights. The tree the hack box was affixed to was ringed by a wide metal collar to stymie mammalian predators and rises up from a deep ravine; the hack box was well off the ground, something that is not evident in these photographs. Image transferred from 35 mm slide: ©Jay Vannini 2022.

The other native owl bred at El Faro were Striped Owls (Asio clamator), a shy owl species mostly restricted to Tropical Dry Forest ecosystems of the Pacific lowlands in Guatemala and more rarely in coastal and riverine areas of Izabal Department on the Caribbean side (Eisermann & Avedaño, 2015). The numbers of young birds encountered in the illicit local wildlife trade in the 1980s and early 1990s suggested that they were far more common than the handful of verified local reports at that time suggested.

Persons who have a real interest in Spectacled Owls in Central America and who would like to read additional information about this release project that I can call up from memory may contact me via the website email: cyclanthaceae@gmail.com.

Mature male and female together with two newly-fledged captive-bred young in an aviary at Finca El Faro, Quetzaltenango, Guatemala in 1989. The naturally-incubated, parent-reared, and non-imprinted juvenile bird in the middle is displaying vigorously in response to the perceived threat that I posed. Image transferred from 35 mm slide: ©Jay Vannini 2022.

References

Eisermann, K. and C. Avendaño. 2015. Los búhos de Guatemala. In: Enríquez, P. L. (ed.) Los búhos neotropicales: diversidad y conservación. ECOSUR, San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, Méico. Pp. 381-434.

Filipiak, D., G. Geisler, D. Kollarits and C. Wappl. 2012. Iguana iguana predation. Natural History Notes, Herpetological Review 43 (3):487-488.

Gómez de Silva, H., M. Pérez-Villafaña and J. A. Santos-Moreno. 1997. Diet of the Spectacled Owl (Pulsatrix perspicillata) during the rainy season in Northern Oaxaca, Mexico. Journal of Raptor Research Vol. 31 (4): 387-389.

Howell, S. and S. Webb. 1995. A Guide to the Birds of Northern Central America. Oxford University Press, USA. 1,010 pp.

Jiménez-Ruíz, B., K. Aparicio-Ubillúz, F. Delgado-Botella and I. Tejada, 2017. The Owls of Panama. In: Enríquez, P. (ed.) Neotropical Owls. Springer. Pp. 579-618.

Land, H. 1970. Birds of Guatemala. Livingston Publishing Co, Wynnewood, PA. 381 pp.

Lindholm, J. 2000. Zoo Bird Profiles: The Spectacled Owl - Pulsatrix perspicillata. The AFA Watchbird. Vol. 27, No. 6. May/June 2000. Pp. 46-49.

Marín-Gómez, O. H., M. M. López-García, Y. Toro-López and J. I. Garzón Zuluaga. 2017. First records of Spectacled Owls (Pulsatrix perspicillata) in urban areas, with notes on reproduction. Northwestern Journal of Zoology (2016). e162602.

Olson. S. 1997. Avian Biogeography in the Islands of the Pacific Coast of Panama. In: The Era of Allen R. Phillips: A Festschrift. Horizon Communications. Pp. 69-82.

Pérez-León, I. Vega and N. Herrera. 2017. The Owls of El Salvador. In: Enríquez, P. (ed.) Neotropical Owls. Springer. Pp. 397-418.

The Peregrine Fund. 2022. Spectacled Owl – Pulsatrix perspicillata. Link: https://www.peregrinefund.org/explore-raptors-species/owls/spectacled-owl

Vannini, J. P. 1989. Neotropical Raptors and Deforestation: Notes on diurnal raptors at Finca El Faro, Quetzaltenango, Guatemala. Journal of Raptor Research, Vol 23 (2): 27-38.

Vannini, J. P. and C. Morales Cajas. 1989. Captive reproduction and successful reintroduction of Spectacled Owls (Pulsatrix perspicillata) in Guatemala. In Burnham, W. A., J. P. Jenny and C. W. Turley (Eds): Maya Project: Use of raptors as environmental indices for management of protected areas and for building local capacity for conservation in Latin America. Progress Report II. The Peregrine Fund, Boise, Idaho. Pp. 105-109.

Vorin, B., R. Kays and M. D. Lowman, 2009. Evidence for Three-toed Sloth (Bradypus variegatus) Predation by Spectacled Owl (Pulsatrix perspicillata). Edentata 8-10: 15-20.

zooinstitutes.com. 2022. Spectacled owl / Pulsatrix perspicillata at zoos worldwide. Link: https://zooinstitutes.com/animals/spectacled-owl-1409/

Acknowledgements

A White-throated Screech Owl (Megascops albogularis macabrus) glares at the photographer from a sheltered spot on a wind-scoured Colombian páramo. This small owl has an extensive range at intermediate to high elevation ecosystems (to over 12,000’/3,700 masl at some localities) across the Andes from western Venezuela to central Bolivia. The flashy eyebrow and throat patch recall their much larger relatives in the genus Pulsatrix. Image: ©Peter Rockstroh 2022.

Many thanks to both Carlos Morales Cajas and Carlos “Cherimoya” Moya for their invaluable contributions to the care, multiple successive breeding, and successful release of these owls at Finca El Faro in the late 1980s. The late Dr. William A. Burnham and J. Peter Jenny, both former Presidents of the Peregrine Fund U.S., provided suggestions for radio telemetry tracking techniques for owls in wet tropical forests based on their then-ongoing research on the ecology of Black and White Owls (Strix nigrolineata) at Tikal National Park in northern Guatemala. The owners of Finca El Faro allowed us to use the private reserve areas on the property to construct a captive native wildlife breeding facility and to conduct conservation research. The Consejo Nacional de Areas Protegidas (CONAP) in Guatemala provided legal permitting and authorization for both captive collections and release of captive-bred wildlife. Peter Rockstroh, Dr. Juan José Arango, and Bill Lamar all contributed images to the article from Colombia and Finca El Faro. The excellent image of Pulsatrix melanota included above was taken in Colombia by David Monroy Rengifo, together with an adult P. p. perspicillata photographed in Perú by Matt and Kaysea Bruce, were used under non-commercial use licenses from Creative Commons. Both photos were slightly cropped for use in this article. The embedded audio clip of the owl call was sampled from a sound file posted online by the Xeno-canto Foundation and is also used under license from Creative Commons.

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC® 2022, ©Peter Rockstroh 2022, ©Juan José Arango 2022, ©William W. Lamar 2022, ©Jay Vannini, 2022, ©David Monroy Rengifo/Creative Commons 2021, and ©Matt & Kaysea Bruce/Creative Commons 2022.

Follow us on: