Quiriguá Interlude

Lightning, Rain & Hurricane

by Jay Vannini

As an avid reader and bushwalker since early childhood, I have long been aware that if you explore nature in the footsteps of interesting, iconoclastic, and intelligent trailblazers you will rarely be disappointed.

Many of the early 20th century biologists, archaeologists, and ethnographers who chose the remote jungles of Mesoamerica as a research destination were brilliant, restless, and intrepid folks to say the least.

“My little specialty is unknown lands.”

And they certainly journeyed paths worth taking.

It is hardly a secret that–especially following very long absences–revisiting places linked to pleasant experiences in one’s youth often proves disappointing. Massive, unexpected (and usually unwelcome) transformations to beloved spots seem invariably to be the norm; even more so when it comes to returning to former wildlands that are no longer the least bit “wild”. It seems the more idealized one’s memories of these places, the more their declines will be found troubling later in life.

Looking back at 50 years of wandering through the colossal, exquisitely-carved Pre-contact era monuments in the Great Plaza at Quiriguá, Guatemala, I was recently struck by how much the site has changed in my lifetime. Regretfully Quiriguá, once perhaps among a handful of the most enchanting of all Mayan sites, appears to have lost some of its luster of late.

So, just what has changed at Quiriguá since 1975?

Despite showcasing an incomparable collection of well-conserved, towering eighth century sandstone portrait stelae, a bit of neglect and climate-fueled natural disasters have not been kind to the grounds they sit on. Nor have they been for the fast-dwindling, degraded forest relict that surrounds the ruins and serves as a buffer against encroaching banana plantations.

This observation aside, the place is still badass.

Above left, a series of exquisitely carved glyphs on the upper section of Stela J - north text. Above right, others on the middle section of Stela J - east text. Quiriguá, Izabal Department, Guatemala. Images: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Lightly disturbed primary forest canopy looking north into the Mayan Biosphere Reserve from the summit of the Temple of the Red Hands/Structure 216 at Yaxhá National Park, Petén Department, Guatemala in July 2005. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Core Mayaland and the Southeastern Periphery

The ancient Mayan cities of the Southern Lowlands are extraordinary, inspiring urban complexes and architectural masterpieces, many of which having unique and–to many–near mystical attributes that must be experienced first-hand in order to appreciate them. This seems especially so on misty dawns and sunlight-dappled twilights when the ghostly touch of supernaturals and murmurs of secretive wildlife exert peak influence on any susceptible visitor’s imagination.

Temple of the Great Jaguar/Temple I, Tikal National Park, Petén Department, Guatemala during the rainy season 2005. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Most of the larger Mayan sites in eastern Chiapas and northern Guatemala that have undergone extensive restorations since the early 20th century are located in densely forested national parks or reserves that also protect native flora and fauna, so are extremely popular with both archaeotourists and ecotourists alike. Some of the better-known Mayan ruins such as Palenque (México), Caracol (Belize), Tikal-Uaxactún (Guatemala), and Copán (Honduras) are popular destinations that attract large numbers of foreign and local visitors annually. These are all heavily promoted by regional package tour operators.

While the larger historical centers generate most of the headline tourist traffic and internet clickbait, the smaller sites have a distinct appeal all their own. Many of the best known images of Mayan iconography, especially those depicted on polychrome ceramics, originate from these smaller cities.

Partial view of the North Acropolis at Yaxhá, Petén Department, Guatemala in July 2005. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Parque Arqueológico y Ruinas de Quiriguá (pronounced keer-ee-GWAH) is a relatively small park located in Los Amates Municipality, Izabal on the southeastern periphery of the Southern Lowlands in the lower Río Motagua Valley near Guatemala’s Caribbean coast. Quiriguá is especially notable for having both the tallest carved monolith in the Americas prior to the 20th century–Stela E at 35’/10.6 m–but also the largest open ceremonial space in the Mayan area, the Great Plaza at >985’/’300 m x 490’/150 m. The size, unique deep relief “Motaguan” carving style, and skilled execution of the monuments both at this site and its sister complex at Copán are considered among the highest artistic achievements of the Maya.

Given its uniqueness and value as global cultural patrimony, Quiriguá was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1981. In 2016 the United Nations also recognized Quirigua’s carved stone texts as historical documentation and as a Memory of the World (UNESCO, 2024).

The discovery and subsequent fame of Quiriguá sparked by northern visitors beginning in 1840 was incidental to U.S. travel writer and diplomat John Lloyd Stevens’ better known explorations at nearby Copán, later recounted in his classic bestseller, “Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan” (1841).

I was very fortunate that my first visit to Quiriguá during the late summer of 1975 coincided with renewed excavations at the site by the University of Pennsylvania a year earlier after almost 40 years of it having been more or less neglected by foreign archaeologists. Crowded by dirt roads and banana plantations that ran right up to the park’s boundaries, its high-forested surroundings that rang with birdsong reminded me I was in the wet tropics and made for an evocative pairing with the stelae. Despite having already visited some beautiful Mayan sites near and along the Río de la Pasión in southwestern Petén Department a month earlier, that first morning’s exploration of the Quiriguá ruins left a deep impression on me that persists to this day.

A clever bon vivant once wrote that it is of little use to treasure these moments when they occur, since this effort only spoils the experience. They are at their best only when remembered later in life.

De acuerdo.

Ballcourt at Copán Ruinas, Copán Department, Honduras during the early dry season, 2019. Image: ©Fred Muller 2024.

For the next 18 months I lived on a rainforest ranch at Corozo, 55 miles/90 km down the highway on the Caribbean coast just east of Puerto Barrios. This work provided me with many opportunities to visit the site while commuting to and from Guatemala City every fortnight or so. Beyond that, I also used to drop by Quiriguá for an occasional stroll between the mid-1980s and the late 2000s.

Partial view of the Great Plaza at Quiriguá at the end of the rainy season, October 2007. Stela F (south face) in the foreground and Stela D directly behind. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

After a 15 year absence, my most recent visit was in June 2024.

Partial view of the opposite perspective of the Great Plaza at Quiriguá in early June at the end of the 2023-24 El Niño-fueled drought that affected much of Central America, Panamá, and parts of western Colombia. North faces of Stelae F and E shown on the margins. Compare with the previous image. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

As is evident in the photos above, it definitely had a very different vibe than it did even as late as 2007.

The Early Explorers, Artists, and Archaeologists

Cropped image of Donã María Josefa Romana y Manrique, wife of the early owner of Quiriguá, Juan Payés y Font, who is shown in the half-length portrait hanging on the wall to her left. Painting by celebrated Guatemalan socialite portraitist Juan José Rosales made in 1791. The artist who painted the likeness of Payés y Font is unknown but the styles of both portraits are similar. Non-copyrighted image. The current owner of this painting is unknown.

Almost a thousand years after its final desertion by coastal Mayan traders in the Terminal Classic or early Postclassic Period, the Quiriguá ruins were discovered by a wealthy Spanish-Guatemalan merchant and later local Consul to the Crown, Juan Payés y Font (1746-1814). Don Juan made an inexpensive speculative purchase, sight unseen, of a large and very wild property (reportedly just over 274 caballerias or 31,000 acres/12,550 ha.*) near the town of Los Amates, Izabal in 1797. The property was then titled Nuestra Señora de Montserrat o Quirigua by Payés y Font and included fertile, heavily forested lowland floodplains on both sides of the Río Motagua southeast to the Río Morja along the foothills of the Sierra del Merendón. On the single visit he made there sometime soon after its acquisition (perhaps in 1798?), he came across a collection of Mayan ruins and carved stones that captured his attention and he reported to his family and acquaintances (Stephens, 1841; Peralta Vásquez, 2010; Crasborne & Navarro, 2011). Despite this savvy acquisition, Payés y Font suffered financial misfortune in the early 1800s with some of his other ventures culminating in negotiations with his creditors and a negotiated bankruptcy (Belaubre, 1999)**. Following his demise, in the late 1830s three of his five children–none of whom had ever visited their “immense” Izabal estate before–who had inherited the then subdivided property began to work on its sale. Inspired by other popular get-rich-quick international real estate schemes of the day, they soon began work on a prospectus to offer the Quiriguá property split as smaller parcels to overseas investors (Stephens, 1841).

After U.S. author and amateur archaeologist John Lloyd Stephens first heard rumors of major Mayan site in the lower Motagua valley while working in Copán and as more reports of the site’s existence surfaced later while in El Salvador, he dispatched his traveling companion, English artist Frederick Catherwood, to explore the locality with two of the owners and a somewhat questionable local guide. Following Catherwood’s favorable reports on the magnificence of the few monuments he had cleared and sketched, Stephens attempted to buy the ruins with an eye to excavating the stelae and sending them to the US for commercial display in New York. This proposal initially received a promising response from one of the Payés y Romana brothers he met with in Guatemala City. Fortunately, in retrospect, after the meeting this brother made inquiries with the French Consul in Guatemala who stymied the sale by convincing him that the site was worth far more than Stephens was able to pay. Despite Stephens’ over-optimistic view that at least two of the larger stelae would soon be on their way to New York by the early 1840s (Stephens, 1841), negotiations failed, and the property and its priceless archaeological inventory remained in the hands of the Payés family until it was sold to the United Fruit Company in 1909 (Crasborne & Navarro, 2011).

Among the most famous early visitors to Quiriguá was British diplomat, polymath, and (later) archaeologist Alfred Percival Maudslay (1850-1931). From 1881 to 1894, Maudslay made four visits of varying durations to the site. His extensive use of the recently developed dry plate photography process to document his finds, many of which were later replicated by photogravure, produced what are widely acknowledged to be the finest images of the monuments at Quiriguá ever made. The very long exposure times coupled with large format photographic technique provide an unmatched level of detail. Maudslay published many of his Quiriguá illustrations and photos in his monumental volumes on archaeology for the Biologia Centrali-Americana (Maudslay, 1899-1902). His prescience in having plaster and papier mâché casts made of several of the stelae and zoomorphs, together with compiling many excellent drawings, has allowed later researchers access to the very fine iconographic detail still evident in the late 1800s that has been lost due to erosion over the past ~130 years.

Maudslay’s cast of Stela E and Zoomorph P, originally housed at the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria & Albert Museum) were later transferred to the British Museum. In 1901 the Peabody Museum at Harvard also had molds made of Quiriguá monuments by Gorgonio and Carolampio López, and the American Museum of Natural History, New York had two Quiriguá casts made in 1902.

Above left, Stela D photographed with an early large format camera by Maudslay’s team following its first full cleaning in 1881, and a similar perspective taken by me with a Nikon DSLR and converted to black and white in 2024. Note the visible loss of some finer carved detail that occurred on the stela’s surface over 140+ years of exposure to the elements. Variation in perspective derives from the monument tilting slightly backward over time. Images: Alfred Maudslay expedition photographer, reproduced from an original resolution, privately-printed plate held in the author’s collection, and ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Later still, the Museum of Man in Balboa Park, San Diego, California had casts of several noteworthy monuments at Quiriguá made for 1915 Panama-California Exposition. All of these replicas are still extant, and most can still be found on display at their respective institutions.

Several professional and amateur photographers visited Quiriguá between 1885 and 1910. Famed Guatemalan portrait specialist Alberto Valdeavellano’s excellent series of photos from 1896, some of which were reproduced in a 1913 issue of National Geographic, complement both Maudslay’s images in the Biologia and William Brigham’s lesser quality plates and illustrations from 1885. Photos from the Peabody Museum’s 1901 expedition, United Fruit Co. Vice-President Minor Keith’s ~1910 images, and the first photos that emerged from the Hewett-Morley excavations that began in 1910 by Jesse Nusbaum that continued for several years after, also include other images that are extremely good (Brigham, 1887; Sands, 1913; Morris in Rice & Ward, 2021; Nusbaum in Rice & Ward, 2021; Cusick at al., 2024).

Above left, Stela F in 1896. Right, Stela C in same year. Images by Guatemalan photographer Alberto Valdeavellano of the Fernández y Valdeavellano studio. Notice the ubiquity of large corozo or cohune (Attalea cohune) palm fronds in the backgrounds of these early images and compare with contemporary views of the site. Images photographed from periodicals in the author’s collection that are out of copyright.

Following the United Fruit Company’s acquisition of Quiriguá in 1909 came a new kind of visitor.

20th Century Mayanists – Some Liked It Hot

We are at a point in our development where executive helicopter shuttles and 4WD tented champagne safaris to El Mirador and other remote Mayan cities in northern Guatemala are–for adventurous and well-heeled–there for the asking. While all this ready access is great, it is worth pointing out that travel and exploration of the Southern Lowlands from the mid-19th century into the 1990s could be a risky endeavor indeed, and some expeditions there ended in tragedy. Quite apart from risks posed by travel in rickety biplanes in remote areas and small boats in the Gulf of Honduras during storms, earthquakes, political upheaval, run-ins with armed bandits, thwarted and pissed-off looters, undisciplined soldiers, and insurgents were more or less continual risks that hovered in the background at many remote digs until fairly recently. Malaria, dengue, yellow fever, cholera (all Old World imports), and Chagas disease are debilitating and life threatening illnesses that are prevalent in many areas of Mesoamerica. Anyone who done manual labor in the region during the dry season (me, for example) also knows how omnipresent the risk of heat stroke is while working out in the sun at >100 degrees F/38 C and almost 100% humidity.

The men and women who embarked on expeditions in dugouts, on foot, or on muleback into often unmapped Mexican, Belizean, Guatemalan, and Honduran jungles at the time were definitely a breed apart.

The fictional hero Dr. Henry Walton “Indiana” Jones is the world’s most famous archaeologist by the widest of wide margins, eclipsing even the equally fictional, tomb-raiding Lara Croft (who, it must be noted, has way better boobs than Harrison Ford), and the widely-celebrated, very real Howard Carter (1874-1939) of King Tutankhamun discovery fame.

Another somewhat depressing lesson from Hollywood about flash over substance is in there somewhere…

There are many backstories about possible inspirations for Indiana Jones posted on the internet, but for me “Indy” is clearly a composite drawn at least subconsciously from the Gringo archaeologist-adventurer-spies who operated undercover in Central America from the 1910s to 1940s. Perhaps he also has a dash of Lester Dent’s muscular pulp fiction hero Doc Savage (originally with an important Mayan connection), who debuted in 1933. The jocular, khaki-clad, “can-do” North American incarnation of scholarly tropical explorers had many archetypes in the early 20th century, several of whom worked the digs at Quiriguá. The most notable were Earl Halstead Morris (1889-1956) sporting his–and Jones’s–signature Stetson hat and who excavated at Quirigua both in 1912 and then in the 1930s; Sylvanus Griswold Morley (1883-1948) who was an erudite, bespectacled socialite, but indefatigable, tough as a tick, and also the archaeologist most associated with Quiriguá and the ancient Maya in general during his day; and Samuel Lothrop (1892-1965), an archaeologist who worked at Quiriguá in 1916 and onward with the Heye Foundation/Museum of the American Indian. Like Morley, Lothrop also spied on German interests (sound familiar?) in Central America for the U.S. government during the World Wars (Browman, 2011).

“Meanwhile, in the deep twilight of a tropical jungle the crumbling remains of this once proud city lie forgotten, its builders unknown and its very name lost in oblivion – a melancholy commentary on its vanished glory. ”

Sylvanus Morley and Earl Morris were both employed by the School for American Archaeology under Edgar Lee Hewett at Quiriguá and Copán in 1912. Morley was also at Quiriguá with Hewett in 1910 and 1911, then later in the decade as was Morris in the mid-1930s with the Carnegie Institute of Washington. Apart from their solo endeavors, both men worked together with the Carnegie together elsewhere in Mesoamerica into later life, most notably at Chichén Itzá in the Yucatán. They remained friendly throughout their careers. There is a remarkable passage in Morris’ 1912 diary from where he describes evacuating Morley, in the throes of malarial fever deliriums and fading fast, from Copán and having had to lash his companion’s feet under his mule to keep him hanging in the saddle.

After arriving at the railroad station just over the border in Zacapa, Guatemala following a miserable and fraught journey, Morley was briefly revived from his stupor by a cold drink and some ice rubbed on his face. Morris then recalls that, “…I went round to the bar for a drink on my own account. Upon my return I witnessed as forceful a demonstration of the relentless drive and unquenchable spirit of the man that I was ever to behold in years of subsequent association. There he sat with shirt open, one trouser leg on, one off, huddled over the ubiquitous notebook. He said, ‘They’ll wreck that inscription for the honey behind it. Got to draw those terminal glyphs before I forget…’ At that point he slumped forward in a dead faint” (Morris in Rice & Ward, 2022).

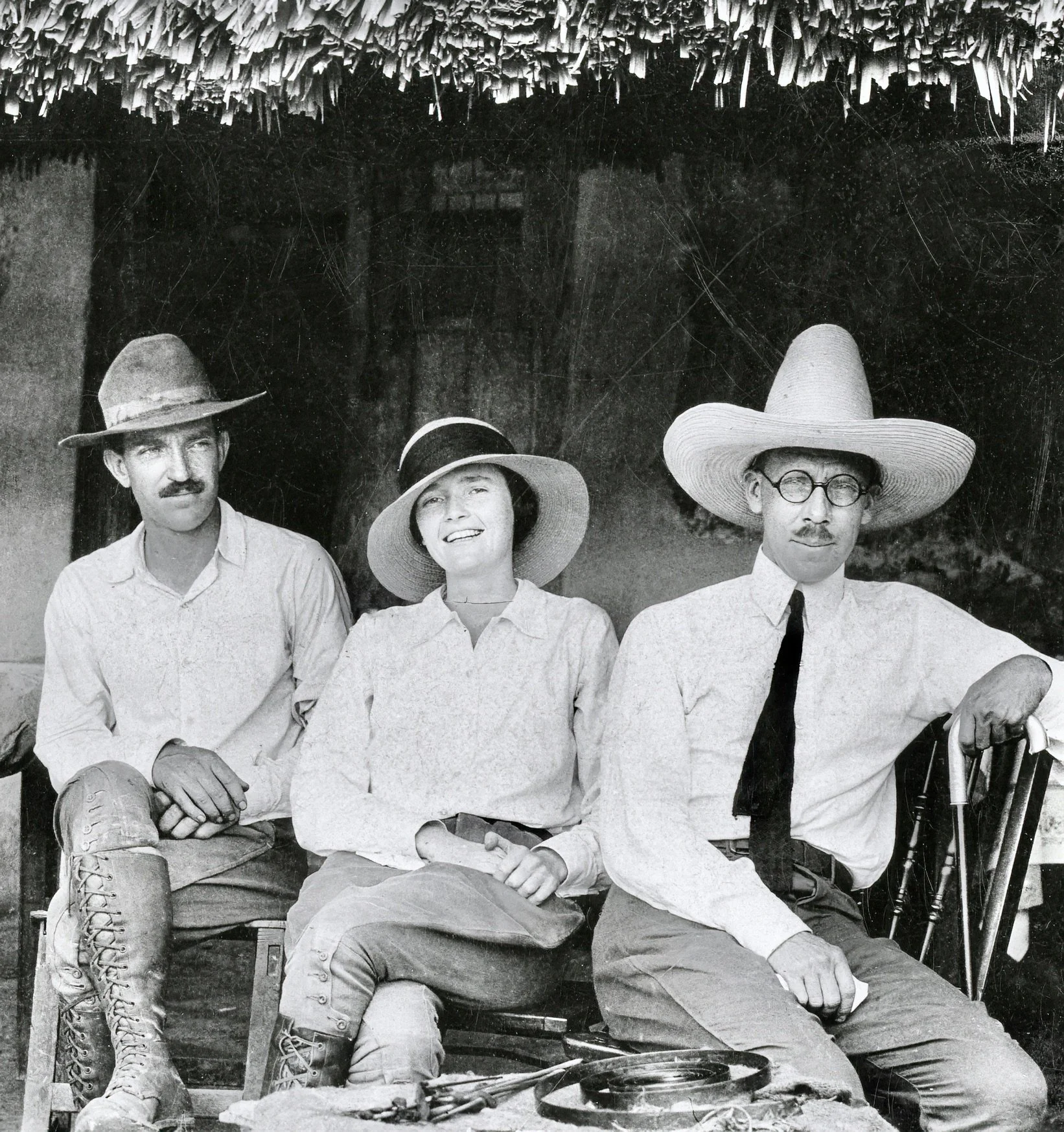

Three famous personalities from early 20th century Mesoamerican and Southwestern U.S. archaeology relaxing in the field at Hacienda Chichén (Itzá), Yucatán State, México in 1924. Left to right, Earl Morris looking thoughtful, a young Anne Axtell Morris with a devil-may-care smile, and a bemused, sombrero-wearing Sylvanus Morley complete with stylish mustache, formal collar, tie, and cane. Image: J. O. Kilmartin, United States Geological Survey/USGS. Non-copyrighted image.

This episode would definitely be considered as suitable Indiana Jones script material.

For those interested in the stories of these men’s work at Quiriguá and Copán, as well as the nitty-gritty of day-to-day management of an archaeological dig in tropical America in the early 20th century, I highly recommend Volume II of the Morley Diaries linked in the Reference section below (Rice & Ward, 2022). Anne Axtell Morris wrote two popular illustrated books on archaeological fieldwork she did together with her husband in the Yucatán and New Mexico, “Digging in the Yucatan” (1931), and “Digging in the Southwest” (1933).

A Dark Place at The Crossroads

The contemporary archaeological park and property title registered by Payés y Font in 1797 takes its name from what was originally an adjacent hamlet named Quiriguá. Unfortunately, no-one has yet figured out the origins or meaning of this name. We do know that during the Classic Period Quiriguá was known in Ch’ol as Uhttiy Ik’ Naahb’ Nal, or “Place of the Black Well”, “The Black Place” (IDAEH, ND) or, alternately, Looper’s (2003) “Place of the Black Lake”.

The Classic Period “port” at Quiriguá may have been located at or alongside a (then) deep section of the Motagua river bed that gave it an especially dark aspect, or that it simply refers to the brown, silt-laden water that accumulates at bends on this river. Alternately, the name may allude more to a deep cosmological black well rather than physical one. Matthew Looper (2003) conjures up a compelling image of Quiriguá’s nighttime Great Plaza and adjacent river as parts of a giant cosmic portal dominated by a “Black Hole” formed seasonally (January to June) by the arc of the Milky Way overhead.

Established by the rulers of Copán as a satellite early in the Classic Period, Quiriguá’s location on a broad waterway that lay at a strategic point between the Honduran kingdoms and cities in the Verapaz and Petén lowlands made it a valuable spot to sponsor a subordinate or close ally.

This relationship seems to have worked out to the satisfaction of the Copanecos for at least a couple centuries.

Stela 31 at Yaxhá showing heavy erosion/weathering/pitting observed on many stelae and altars in the Petén. This object is lying on the ground, not elevated. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

The rhyolite and hard brown sandstone quarried just to the north of the Quiriguá acropolis that was likely transported via wooden rollers to the site weathers far more slowly than the marine limestone used for monuments elsewhere in the Southern Lowlands. Nonetheless, it is obvious from a comparison of the photos shown here that were taken in the late 19th century against contemporary ones, that the 80 or so years in the 20th century that the stelae were unprotected from sun and rain erased a lot of the finer details on both stelae, altars, and zoomorphs. This loss of detail is, however, generally less noticeable than that observed on limestone monuments elsewhere in the Southern Lowlands.

Pre-Contact defacing of some monuments at Quiriguá is believed to have occurred after having been overrun by rivals, especially in the 6th century, although some noteworthy damage is recent. Facial features, etc. are known to have been broken when stelae fell over during excavations and erection in the early 20th century. Graffiti carved into the stelae was reported as early as 1885 and 1919; then into the contemporary (Brigham, 1887; Crasborne & Navarro, 2011; Morley in Rice & Ward, 2022), prompting low barriers to be erected around the monuments in the late 1970s. Natural palm and later synthetic thatch overhead cover was provided to the stelae and zoomorphs beginning in the 1990s to limit further weathering.

Beside loss of canopy, deep silting from the river’s periodic overflows is an ever present danger to the site. Even after removal of the effects of recent mud events, the accumulation of silt over the centuries has been such that the original level of the Great Plaza was certainly more than 3’/100 cm below where it is now (Looper, 2003). Bancroft (1875) and Maudslay (1902) cite Austrian naturalist and explorer Karl Scherzer’s account published in 1855 of reports by locals of flooding at Quiriguá in 1852 that rose so high that several of the stelae were undermined and toppled. Indeed, Scherzer was apparently unable to find Stelae E and F sketched by Frederick Catherwood 15 years earlier, so clearly some major transformation had occurred to the monuments’ upright positions in the interim.

While long-recognized as a key center for trade throughout the Southern Lowlands and beyond, evidence for exactly which items and in what volumes moved through it seems more intuitive than conclusive. There is, however, considerable physical evidence showing that Quiriguá was major distribution center for obsidian artifacts. Analysis points to origins from surface mined sources, mostly at El Chayal in Guatemala Department, and later from the slopes of Volcán Ixtepeque in Jutiapa Department (Golitko et al., 2012). Given its close proximity to sources of “luxury” commodities for the Maya elite such as jadeite, specular hematite, plumes (esp. quetzal [Pharomacharus mocinno], cotinga [Cotinga amabilis], and macaw [Ara macao]), animal hides, cacao, and coastal commodities such as spiny oysters (Spondylus americana) and stingray (Dasyatidae) spines, it is likely these items also figured in trade to and from Quiriguá. The large expanses of fertile, flat, lower Motagua flood plain immediately alongside the city was almost certainly a major corn producing area on the periphery of the core Mayan region.

Two separate accessions of copper bell/cascabel trade items recovered at Quiriguá that date from the early Post Classic Period (950 to 1200). The items were likely cast by artisans located further north in México and made their way south to eastern Guatemala and Honduras by way of coastal traders. Collection of the Museo Nacional de Antropología y Etnología de Guatemala. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

In recent historical times, due to ease of access provided by the opening of the Northern Railroad in the mid-1890s that initially included a terminus at Los Amates, Quiriguá was readily accessible to visitors from both the Guatemalan highlands and, later, Puerto Barrios on the Caribbean coast. Inauguration of the CA-9 highway from Guatemala City to Santo Tomás de Castilla that passed nearby was concluded in 1954 and provided easier access still. At least into the early 1960s, Quiriguá was likely the most visited–and safest–Mayan site anywhere in the Southern Lowlands (Morley, 1935; Jackson, 1937; Kelsey & de Jongh Osborne, 1952).

The Court of the Lightning King

Stela D, detail of north surface - a carved portrait of Quiriguá’s formidable ruler K’ak’ Tiliw, “The Lightning Warrior”. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Quiriguá is considered to have been a small ceremonial and trading post rather than a well-developed urban center, and the peak population in its center and immediate vicinity probably numbered somewhere around a couple thousand individuals (Looper, 2003).

Now located more or less midway between the CA-9 highway, the now abandoned Northern Railway line, and the Río Motagua, at its heyday in the 700s it was also a port. The river has shifted its course a couple miles/km east on the floodplain over the centuries, so the ruins are now located some distance from its banks.

Stela A at Copán Ruinas. Dedicated on January 39, 731 and depicting the ill-fated Uaxaclajuun-K’awil/18-Rabbit providing a handy perch for reintroduced scarlet macaws (Ara macao) from the Macaw Mountain project. Image: ©Fred Muller 2024.

There is evidence that Quiriguá was occupied as early as the first century in the Late Formative Period, with carved texts documenting its growth in the Early Classic Period sometime after 400 CE. The archaeological record suggests that it was depopulated in the late fifth through until the mid-seventh centuries (perhaps due to a catastrophic attack by a rival and/or hurricane damage), followed by its revival, commercial rise, and political ascendancy from 725 until the early 800s.

Most of the monuments that make the site famous were constructed in second half of the 8th century by a long-lived, bearded ruler formerly known from hieroglyphics as K’ak’ Tiliw Chan Yo’ at/Yo’ pat, now spelled K’ak’ Tiliw Chan Yo’aat and abbreviated to K’ak’ Tiliw. The different components of this name allude to “fire”, “sky”, and a lightning deity (Looper, 2003). Popular works also refer to this king, who ruled Quiriguá from 725 to 785 as Cauac (= Lightning or Stormy) Sky. Archaeologist Matthew Looper christened him the “Lightning Warrior” in his major work on Quiriguá published in 2003.

Evidence suggests that a carefully negotiated and surreptitious strategic alignment with rulers of the powerful Snake Kingdom at Calakmul in Campeche ultimately prompted K’ak’ Tiliw to rebel against the subjugation of Quiriguá by the Copán elites (and, by extension, the rulers of Calakmul rival Tikal) in the early eight century. Following this successful revolt in 738, texts show that in 756 he assumed the prestigious Classic Maya royal title, “Kalo’mte”, as well as “Man of the Black Place in the Dream” (IDAEH, ND).

I refer readers to Looper’s “Lightning Warrior” (2003) for other information and an exhaustive telling of Quiriguá’s ancient history other than to emphasize one key event that proved the catalyst for creation of most of the amazing portrait statuary erected at Quiriguá: The capture and execution of the ruler of Copán, 18-Rabbit on May 03, 738. Despite this shocking coup d’etat by a far smaller power, this event does not appear to have prompted retribution by the Copanecos, and there is no apparent later conflict recorded between the two cities in the archaeological record.

The Lightning Warrior used much of his reign establishing a cult of personality among his subjects. Besides a few fauna-influenced zoomorphs, most the monuments dedicated at Quiriguá between 746 and 785 pay homage to K’ak’ Tiliw in one form or another.

See the image Gallery at the end of this article.

Forest Decline and Fall

Despite its small size the extensive photographic record available that documents the transformation of the native vegetation at Quiriguá, coupled with botanical exploration of the area in the 1940s and beyond (Standley & Steyermark, 1958), make it an interesting case study in relatively rapid loss of biodiversity at a protected plot in the wet tropics.

Much of the change evident is the byproduct of excavation and restoration of the site. The importance of keeping monuments, staircases, and other structures safe from the danger of tree falls in an area where hurricanes are fairly frequent visitors is understandable. We know from reports by early archaeologists that some of the stone monuments and buildings were accidentally struck by giant trees felled during clearing, even after safeguards such as cables and pulleys were employed to direct the falls away from stone objects and constructions (Morley, 1913).

The repetitive deforestation and firing of felled trees and undergrowth by archaeologists that took place in and adjacent to the Great Plaza and the Acropolis at Quiriguá from 1880s until the 1970s has definitely had a severe and lasting impact on the diversity of tree cover and epiphyte loads occurring there today. As the complex forest communities located north of it in the depression between the eastern terminus of the Sierra de las Minas and the western end of the Sierra de los Micos were erased by the agricultural frontier via slash and burn, coupled with later conversion of the flood plain to banana plantations and cattle pastures, floral germplasm reserves have been pushed even further away from the Quirigua isolate/forest relict.

Beyond the issue of the loss of regional native seed sources, an active climate cycle in the region that would seem to be accelerating since the late 1990s has severely degraded the forest fragment remaining there.

Drought killed mature epiphytes in mid-canopy, primarily Anthurium schlechtendalii (Araceae) and Aechmea mexicana (Bromeliaceae) photographed at Quiriguá, early June 2024. This phenomenon was observed in both standing forest and forest fragments across wide areas of the eastern Izabal lowlands over the following days. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Whatever one’s views on anthropogenic climate change, the negative effects of a dynamic climate cycle are now definitely conspicuous at Quiriguá.

Despite being located in an area that normally receives abundant rainfall throughout much of the year, contemporary cyclical droughts prompted by severe, widespread El Niño events are producing changes in the species composition of tree cover around the region that will ultimately favor plant communities tolerant of extended dry seasons.

From my own experience farming and doing conservation fieldwork in the lower Motagua and Caribbean coast of Guatemala, coupled with comments made by other local ranchers and banana growers, during the 1970s and 1980s, annual rainfall totals in the 90”/2,250 mm range were considered normal. Guatemala has a bimodal rainy season with most of the rain falling between mid-May and mid-November, with peaks usually evident in June and September.

Precipitation totals in the region appear to be on a sharp downward trend recently, and the microclimate has undergone a major change over the past few decades. For one extreme example, from the beginning of January through mid-June 2024, accumulated rainfall totals were a scant ~8”/200 mm” vs. a comparative historical average of ~30”/750 mm (Weather api, 2024; pers. obs.). This is just over one-quarter the average amount of precipitation that falls at Los Amates and is likely to be the lowest total recorded for the same dates in recorded history. Almost all rainfall in June 2024 occurred in the second half of the month (just after my latest visit), when Guatemala was pummeled by torrential rains from low pressure systems that lingered along both coasts. The effects of these storms were still insufficient to erase the extreme rainfall deficit recorded during the first semester of 2024.

Completely desiccated and fissured ground on the Great Plaza at Quiriguá in early June at the end of the 2023-24 drought. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

On the other hand, extreme weather can produce alarming amounts of rainfall in short periods. Below is a list of major late 20th and early 21st century hurricanes that caused the Motagua to overflow its banks at Quiriguá, resulted in extensive flooding, felled trees, and otherwise having had noticeable negative impacts on the site:

Fifi-Orlene 1974

Mitch 1998***

Stan 2005

Dean 2007

Agatha 2010

Eta 2020

Iota 2020

Several of these inflicted significant damage to properties and infrastructure on the lower and middle Motagua Valley in general and to the Quiriguá archaeological park in particular.

Signage at Quiriguá showing before and after images of one corner of the Great Plaza following Motagua flooding associated with severe back-to-back Tropical Storms in November 2020. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

One of the earliest key findings from research into the ecological dynamics that occur in isolated lowland tropical forest fragments in Brazil during the 1980s (at that time called the Minimum Critical Size of Ecosystems Project) was the outsized impact of what is now known as the “Edge Effect” (Bierregaard et al., 1992). This can be summarized as showing that the smaller the isolate, the greater the edge to area ratios and so the variations in light, temperature, and humidity measured within them due to the proportionally larger surface area within exposed to the brighter, hotter, and drier world outside. Observations made elsewhere in the wet tropics have confirmed the dramatic loss of biodiversity that occurs in the years following forest fragmentation, especially in sites where the distance to the closest standing forest block is significant.

This is clearly evident to me after watching the gradual qualitative decline of the environment of the secondary forest isolate at Quiriguá since 1975.

Above, two examples of (many) dead and severely stressed trunk epiphytes in the understory at Quirigua observed at the end of the 2023-24 drought. Left, Anthurium schlechtendalii (Araceae), and right, Selenicereus minutiflorus (Cactaceae). The flowers of these plants are insect-pollinated and their fruits are bird and mammal-dispersed, so their loss will have immediate knock-on effects in both this and surrounding ecosystems. Both of these plant species are normally capable of withstanding lengthy dry spells without suffering much visible damage so the severity of the drought is evidenced in these photos. Images: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Sylvanus Morley (in Rice & Ward, 2022) mentioned a conversation with a U.S. tropical forester at Quiriguá in the early 1900s who opined that the old-growth forest on the opposite side of the Motagua was not especially diverse, and likely was the product of earlier clearing during Pre-Contact occupation of the valley. It has long been known that climax forest communities at larger Mayan sites throughout the Southern Lowlands tend to share high numbers of a relatively low number of tree species*** when compared to what are presumed to be undisturbed forests (Lundell, 1937). However, both Quiriguá and Copán are outliers from this general rule applicable to almost every other site in southeastern México and northern Guatemala. Although situated at a lower elevation, much like Copán Ruinas, Quiriguá is proximate to a several mountain ranges whose foothill wet forest ecosystems are now known to be exceptionally diverse and rich in noteworthy floral endemics (Standley & Steyermark, 1958; Vannini et al., 2022; pers.obs.).

Species-diverse, climax tropical foothill forest in the Sierra del Merendón facing the lower Motagua valley ~30 mi/48 km airline from the Quiriguá ruins during March 2014. Similar forests occur on the opposite side of the Motagua plain a few miles/km north of Quiriguá in the Montaña del Mico, as well as to the southwest closer to Copán Ruinas. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Final Thoughts

Comparison of older (ca. 1910) and contemporary (2024) images shown here of the forested surroundings that frame the monoliths at Quiriguá make it obvious to even a casual observer that the current state of health of the park’s mini-ecosystem needs attention in order to conjure up a bit more of what Sylvanus Morley called its “vanished glory”.

Some will argue that Quiriguá in its heyday in the mid-700s was likely devoid of all forest cover and even more denuded of vegetation than it is now, so what is my complaint?

Quiriguá is a unique living historical site and Mesoamerican archaeological treasure. The stelae, altars, and zoomorphs–viewed outside of the context of a lush tropical forest surrounding them–are for all practical purposes nothing much more than museum exhibits rather than a tribute to the magic of Mayan Forest (see Jackson, 1937 for an even more scathing opinion on this topic). There is no doubt that the older images of Quriguá that were made when primary forest still hovered close in the background gave them a romantic mystique that is sorely lacking today. There are many other reasons (such as improved erosion control provided by vegetation brakes) why a reconstruction of some semblance of the 19th and early 20th century wet forest parklands that surround the ruins should be given priority by the relevant authorities.

Based on my own experience in Guatemala with private reforestation and forest enrichment projects, restoration of the park’s forest reserve seems pretty straightforward and could begin almost immediately. The site lends itself especially well to being developed as an arboretum showcasing native trees based on the floral community formerly native to the area. It is likely that improved canopy quality would prove a welcome feature for some noteworthy native birds that have deserted the area (Land, 1963). Forest enrichment at Quiriguá should begin with reforestation using the signature arborescent species that the occurred at the ruins during the early 20th century, starting with corozo palms (Attalea cohune), until recently a handsome and occasionally emergent tree species abundant throughout Izabal Department. Supplemental irrigation will almost certainly be required for some species during periods of extended drought; fortunately, a permanent source of water is available nearby that makes the logistics of countering future rainfall deficiencies a feasible endeavor.

The flip side is to risk a permanent cycle of yoyo-ing between desertification and severe flooding of the site.

Safe travels.

Footnotes

*Later, apparently undocumented claims, invariably cite 50,000 acres/20,000 ha. as the property’s size when first acquired by the Payés family. It is unclear whether the Payés added additional lands to this property between 1800 and its sale to UFCO in 1909.

**Coincidentally, close association with Quiriguá is linked to some largely unrelated but high-profile bankruptcies among its wealthy early promoters, including Payés y Font, Brigham, and Maudslay.

***Hurricane Mitch was the deadliest storm to hit the Central American mainland in recorded history. The damage that it did to regional old-growth forest canopy cover, infrastructure, and agriculture is incalculable.

****Typical canopy communities at Mayan ruins in the lowlands are dominated by relatively few tree species: broadleaf mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla), Spanish cedar (Cedrela odorata), breadnut (Brosimum alicastrum), ceiba (Ceiba pentandra), chicozapote (Manilkara zapora), mamey zapote (Pouteria sapota), gumbo-limbo (Bursera simaruba), botán palm (Sabal spp.), and corozo or cohune palm (Attalea cohune).

Gallery

Images are arranged by monument type and in chronological order of their dedications. Dates from Looper (2003), measurements from Morley (1935).

Stela H, 17.5’/5.18 m tall, east face. Dedicated May 09, 751. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Stela J, 16’/4.88 m tall, west face. Dedicated April 12, 756. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Stela I, 13.5’/4.14 m tall, west face. Dedicated April 12, 756. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Stela F, 24’/7.32 m tall, south face. Dedicated March 17, 761. Image: Jay Vannini 2024.

Stela E, 35’/19.67 m tall, north face. Dedicated January 24, 771. This the tallest ancient monolith ever discovered in the Americas. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Stela C, 13.1’/3.99 m tall, south face. Dedicated December 29, 775. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Stela K, 11.5’/3.51 m, west face. Dedicated July 22, 805. An odd man out here, this stela was commissioned and dedicated by Jade Sky, the last known ruler of Quiriguá. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Above left, Zoomorph M. Dedicated August 20, 731. This chimeric jaguar head stone marker is notable for being the first monument discovered at Quiriguá that has the city’s emblem glyph carved into it, perhaps foreshadowing its independence from Copán a few years later. Above right, Zoomorph N. No inscriptions but likely dedicated ca. 734. It is now believed to have formed a basal pair with Zoomorph M that supported Altar L (shown below) at the base of the stairs leading to the ballcourt at Quiriguá. When Alfred Maudslay first discovered this object in 1883, it was broken in two parts (fracture line visible), overgrown by an immense tree, and partially enveloped in its buttress roots. It was first repaired by Edgar Lee Hewett in 1911. The figure is a turtle-backed deity known as the world bearer. Images: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Zoomorph B, south face. Dedicated November 06, 785. Based on traces of pigment persisting on both this and Zoomorph P, it is believed that the monuments at Quiriguá were all coated in red paint during the site’s active occupation. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Zoomorph P, north face. Dedicated September 15, 795. The largest and most intricately detailed zoomorph known from the western hemisphere. It is unclear whether these ornately carved boulders may have served multiple roles for propaganda purposes, thrones, and/or platforms used to display sacred or sacrificial objects. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Altar L, carved from rhyolite and associated with Zoomorphs M and N shown above. Dedicated June 2, 653. Collection of the Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología de Guatemala. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Altar pair of Zoomorph P. Dedicated September 15, 795. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

In the pre-dawn of February 04, 1976 a catastrophic earthquake with a surface-wave magnitude of 7.6 struck Guatemala causing major loss of life, especially in the central highlands. Its epicenter was located at Los Amates, which is a major center for seismicity along the Motagua Fault, and is proximate to Quiriguá. Somewhat surprisingly, only moderate damage was recorded for Stelae E, H, J, and the Acropolis. The image above shows the west face of Stela H at Quiriguá after preliminary stabilization from that earthquake’s damage. USGS image from 1976, non-copyrighted.

References

Bancroft, H. H. 1875. The Native Races of the Pacific States. Vol. IV. Antiquities. Chapter IV. Antiquities of Guatemala and Belize. H. O. Houghton and Company. 106-140.

Belaubre, C. 1999. Cuando los curas estaban en el corazón de las estrategias familiares: el caso de los González Batres en la Capitanía General de Guatemala. Anuario de Estudios Bolivarianos 7/8. 119-150. https://www.afehc-historia-centroamericana.org/diccionario2/diccionario_fiche_id_97.html

Bierregaard, Jr., R. O., T. E. Lovejoy, V. Kapos, Augusto dos Santos, A., and R. W. Hutchings. 1992. The Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments. In: Stability and Change in the Tropics. . Bioscience, Vol. 42, No. 11. 859-866.

Brigham, W. T. 1887. Guatemala: The Land of the Quetzal. Charles Scribners & Sons, NY. vii + 442 pp.

An underappreciated narrative on conditions in late 19th century Guatemala based on noted botanist, ethnologist, and photographer William Tuft Brigham’s extended visit to the country in 1885. His earlier investments in Guatemala resulted in bankruptcy for a partnership he was involved with, and humiliating (if unproven) charges of embezzlement that cast a shadow over the rest of his life. Brigham visited Quirigua while on his return trip to the Caribbean and photographed and sketched several stelae a year after Maudslay’s second excavations there.

Browman, D. L. 2011. Spying by American Archaeologists in World War I. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology. Volume: 21. Issue: 2. 10-17. https://archaeologybulletin.org/articles/10.5334/bha.2123

Crasborne, J. and H. Navarro. 2011. Natural Hazards and the Cultural Heritage of Guatemala: An Overview from the Vantage of the Quirigua Archaeological Park. Mesoweb. 1-11. https://www.mesoweb.com/articles/Quirigua/Crasborn-Navarro-2011.pdf

Cusick, A., S. Faber, D. Loren, and J. Carballo. 2024. The Fruits of Extraction: United Fruit Company, Archaeology, and Harvard’s Peabody Museum. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/ad4056c82d2e4cc887e9e70bb46dc99d

Yet another example of indignant huffing and puffing by contemporary social justice torchbearers about UFCO’s passage in Central America that is heavy on Harvard alum guilt and light on any sense of proper historical context. For those interested in this topic, I suggest “Bitter Fruit” (Schlesinger & Kinzer, 1983), and “The Fish that Ate the Whale: The Life and Times of America’s Banana King” (Cohen, 2013) as better primers. While navigating the text of this presentation is tiresome, the slide deck does contain some valuable early images of Quiriguá monuments taken by visionary entrepreneur and banana baron Minor Keith that are apparently not published elsewhere.

Espinosa, A.F. (Editor). 1976. The Guatemalan Earthquake of February 4, 1976, A Preliminary Report. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1002. United States Government Printing Office. ix + 90 pp. https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/1002/report.pdf

Documents 1976 earthquake damage at Los Amates and Quiriguá including photographs.

Golitko, M., Meierhoff, J, G. M. Feinman, and P.R. Williams. 2012. Complexities of Collapse: The Evidence of Mayan Obsidian and Revealed by Social Network Analysis. Antiquity (86). 507-523. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Terminal-Classic-period-AD-800-1500-obsidian-frequencies-All-symbology-is-otherwise_fig4_230760694

Instituto de Antropología e Historia (IDAEH). Undated. Parque Arqueológico Quiriguá: Guia de visita. 1-14. https://mcd.gob.gt/informes/ruta/Finiquitos/Otros/GUIA_QUIRIGUA_OFICIAL_ESPAniOL.pdf

https://mcd.gob.gt/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/desplegable-ingles-v2021.pdf

Jackson, J. H. 1937. Notes on a Drum - Travel Sketches in Guatemala. The Macmillan Company, NY. x + 276 pp.

The first travelogue that profiles the early transition of modern Guatemala during the Ubico administration. Briefly popular when published, it was written by California historian, literary editor at the San Francisco Chronicle, and radio talk-show personality at NBC, Joseph Henry Jackson. He and his wife embarked on a lengthy package tour throughout the central highlands and the lowlands of both coasts in the late fall of 1936 that culminated with a visit by train to Quiriguá. Long on colorless anecdote and short on adventure, the book does contain 64 black and white photographs that are of interest to historians, along with sketches of notable ex-pat personalities of the day. Jackson was–to put it mildly–unimpressed with Quiriguá and its many contemporary enthusiasts, and invested several pages critiquing what he found to be its museum-like atmosphere and excessive hype as a romantic destination by Deep Thinkers of his day. This contrarian view appears almost unique for the period.

Kelsey, V. and L. de Jongh Osborne. 1952. Four Keys to Guatemala. Fifth Edition. Funk & Wagnalls Co., NY. xiv + 332 pp.

Land, H. C. 1963. A Collection of Birds from the Caribbean Lowlands of Guatemala. The Condor. Vol. 65. 49-65.

Includes a visual record of a flock of scarlet macaws (Ara macao) on the north shore of Lake Izabal near Quiriguá in the late 1950s. The presence of wild scarlet macaws on Lake Izabal and at Quiriguá is mentioned with some frequency in early 20th century travelogues and at least one was collected there by Earl Morris in 1914. Based on interviews I had with local coastal residents in 1975, this conspicuous species was likely extirpated on the lake and Río Dulce and also in the lower Motagua Valley by the late 1960s or early 1970s. The popularity of liberty scarlet macaws at nearby Copán suggests they would also be a nice touch at Quiriguá.

Looper, M. G. 2003. Lightning Warrior. Maya Art and Kingship at Quirigua. University of Texas Press. xi + 265 pp.

Twenty years on, still the best work on Quiriguá by the man who first documented the reign of K’ak’ Tiliw and, together with earlier efforts by archaeologist David Kelley, deciphered many of the site’s glyphs.

Lundell, C. L. 1937. The Vegetation of Petén: With an Appendix of Mexican and Central American Plants. Carnegie Institution of Washington. Publication No. 478. 244 pp.

Maudslay, A. C. 2022 (1899). A Glimpse at Guatemala, and Some Notes on the Ancient Monuments of Central America: With Maps, Plans, Photographs and Other Illustrations. Legare Street Press Reprint (originally John Murray, London). xvii + 289.

Maudslay, A. P. 1889-1902. Biologia Centrali-Americana; Contributions to the Knowledge of the Fauna and Flora of Mexico and Central America. Edited by F. Ducane Godman and Osbert Salvin. R. H. Porter, London and Dulau & Co, London. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/105791#page/83/mode/1up

Morley, S. G. 1913. Excavations at Quirigua, Guatemala. The National Geographic Magazine. March 1913. Volume XXIV, Number 3. 339-361.

Morley, S. G. 1935. Guide Book to the Ruins of Quirigua. Carnegie Institution of Washington. Supplementary Publication No. 16. vii + 205 pp.

A compact and informative, if dated, handbook written for tourists visiting the Quirigua ruins while it was still fairly wild. It is a quick and easy read, unlike some of Morley’s technical treatises on the Maya. Copies in excellent condition may still be found online for surprisingly affordable prices.

Morris, A. A. 1931. Digging in the Yucatan. Doubleday, Doran & Company, New York. xvii + 279 pp.

Morris, A. S. 1933. Digging in the Southwest. Doubleday, Doran & Co. xviii + 301 pp.

Murga, G. P. 1986. Núcleos de poder local y relaciones familiares en la ciudad de Guatemala a finales del siglo XVIII. Mesoamérica 12. 241-308.

Ordoñez Jonama, R. 2003. Nuestra Señora de Rosario de Chiquinquira y la Familia Romana. Academia de Ciencias Genealógicas y Heráldicas de Bolivia. 1-29.

This paper contains a valuable and detailed history of the Payés y Font and Romana lineages that mentions the Quiriguá purchase and some of Payés’ later financial woes.

Peralta Vásquez, A.C. 2010. Representación Gráfica Virtual y Análisis de la Arquitectura y Urbanismo del Sitio Arqueológico Quiriguá. Universidad de San Carlos, Facultad de Arquitectura. 179 pp.

Rice, P. and C. Ward (Eds). 2021.The Archaeological Field Diaries of Sylvanus Griswold Morley, 1914. The Morley Diary Project, Volume I. xi + 373 pp.

https://www.mesoweb.com/publications/Morley/index.html

Mesoweb is a professionally-curated, top-tier resource for those interested in all aspects of Mesoamerican archaeology. The Morley Diaries Project is–in my view–one of the finest and most readable additions to this website. Expertly edited, exhaustively researched, and extensively footnoted.

Rice, P. and C. Ward (Eds). 2022. The Archaeological Field Diaries of Sylvanus Griswold Morley: Excavations at Quirigua, 1912 and 1919. vi + 301 pp. https://www.mesoweb.com/publications/Morley/Morley_Diaries_Quirigua.pdf

Together with Matthew Looper’s Lightning Warrior, these diary entries and articles provide the deepest of dives into Morley’s fieldwork in Guatemala and elsewhere, as well as the ancient history of Quiriguá. Morley’s diaries from Quiriguá provide real insights into the challenges of staffing and managing a major archaeological dig in Mayaland back in the day.

Sands, W. F. 1913. Mysterious Temples of the Jungle: The Prehistoric Ruins of Guatemala. The National Geographic Magazine. March 1913. Volume XXIV, Number 3. 325-338.

Standley, P. C. and J. A. Steyermark. 1958. Flora of Guatemala. Volume 24, Part I. Chicago Natural History Museum. ix + 478 pp.

Stephens, J. L. 1858 (12th Edition). Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan. Harper & Brothers, Publishers. vii + 474.

United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 2024. Archaeological Park and Ruins of Quirigua. World Heritage Convention. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/149/

Vannini, J., T.B. Croat, and J. J. Castillo Mont. 2022. New species and a new combination of Anthurium (Araceae) from Central America. Aroideana Vol. 45, No. 2. 471-532.

Describes and discusses new microendemic plants from eastern Izabal Department, Guatemala with notes of regional floral diversity near Quiriguá.

Villela, K. 2015. Viajes Pintorescos y Archeológicos (sic): The case of the Quiriguá vase. Pasatiempo, Santa Fe New Mexican. 5 pp.

Weather api. 2024. Los Amates Historical Weather.

Zoomorph P with Edgar Hewett in 1910. Image by Jesse Nusbaum, School of American Archaeology, out of copyright.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Fred Muller for providing the photos of Stela A with a pair of reintroduced scarlet macaws as well as the ballcourt at Copán Ruinas in Honduras during the 2019 dry season.

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC®, ©Jay Vannini 2024, and ©Fred Muller 2024.

Follow us on: