Fred's Island

by Peter Rockstroh

The cast of “Gilligan’s Island in 1964, with Gilligan (Bob Denver) seated lower center. Image ©CBS Broadcasting Inc. Used under license.

If you are a Baby Boomer and grew up in the U.S. or Latin America, chances are that you are familiar with, and perhaps even a closet fan of, Gilligan’s Island. If you don’t have a clue what I’m talking about, you are either part of Gen Alpha or Z, belong to an obscure religious sect that doesn’t allow TV and magazine reading, or lived outside the range of U.S. sitcoms in a cave somewhere in northern Maine or Tierra del Fuego. To level the playing field cross-culturally a bit and make a long story short, Gilligan’s Island is the title of a U.S. sitcom that ran from 1964 through 1967 and that was heavy on the kind of slapstick humor guaranteed to keep young children rolling around on the floor in stitches in front of the TV. The plot revolves around the adventures and privations of seven very different and unlikely individuals who embark on a (supposedly) short pleasure cruise on the SS Minnow when a sudden typhoon sweeps them off course and they shipwreck on an unmapped and deserted tropical island, presumably somewhere just a bit west of Catalina off the coast of Los Angeles, California.

The party spends years on the island going coconuts and hoping for a rescue that never occurs during the original series. Among the positive messages of Gilligan’s Island, amidst all of its overacting, hair-brained antics and pratfalls, is that a good sense of humor is a very valuable attribute when faced by adversity and both hope and life always find a way.

Following a 10 day-long excursion with a companion to Amazonian Perú in late February and early March of 2020, a photographic contributor of ours, tropical nature guide and chef to the lost and isolated, Fred Muller, was stranded in country. Arriving at the international airport in Lima about 30 minutes too late to catch the last plane out to Panamá City, he was swept up in the vortex of Shitstorm/Huracacán COVID-19. His much luckier Gringo wingman abandoned him with a wave goodbye and a wish for good luck, and was just able to hop one of the final flights back to the ‘States right before the bell tolled at midnight and Perú entered a pandemic-prompted lockdown that continued through until October 2020.

Twenty-four hours later–dazed, bedraggled and dismayed, he was cast on the sunlit, sandy beaches of faraway Tingo Maria. Just the names of the exotic landmarks in the vicinity of this town–the Cave of the Owls and the Sleeping Beauty–make for a great story and a wonderful travel destination…

…unless you are forcibly stranded there for a a very long time.

¡Santo Cielo! But what big teeth you have, amiguito! Pallas’s mastiff bat or lookalike (Molossus cf. molossus) moments before slicing Fred’s thumb to pieces. Image ©F. Muller 2020.

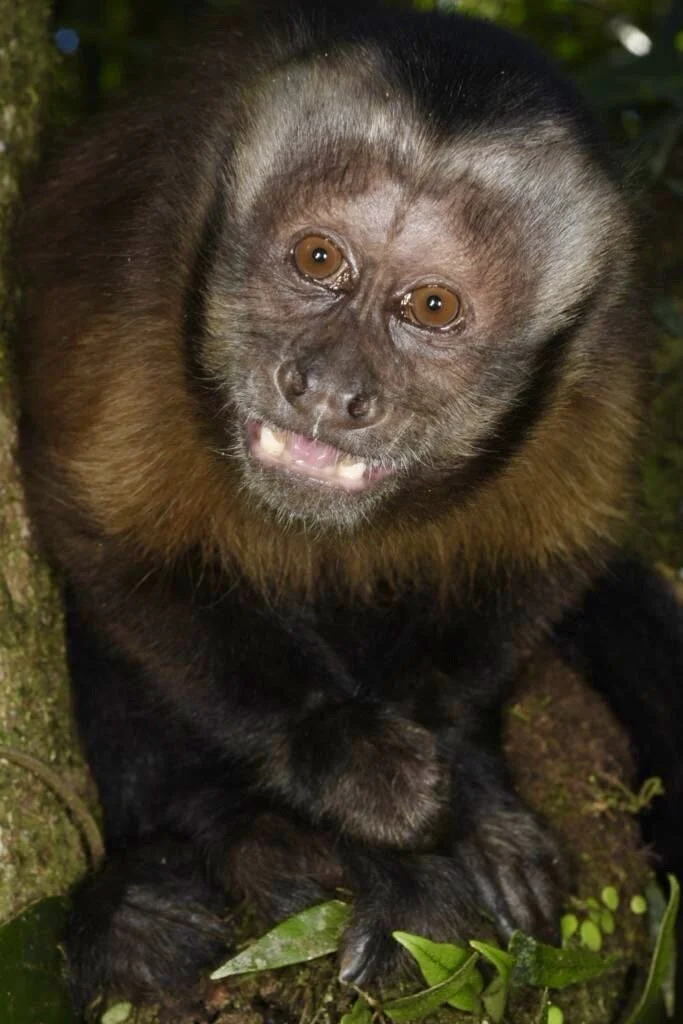

Roughly 47,000 people inhabit Tingo Maria, located in the upper Río Huallaga valley and capital of the Leoncio Prado Province in the central part of the country. It is the seat of two well-known Peruvian universities, the University of the Jungle and the University of Huánuco. Being the political, commercial and intellectual hub of the region, Fred was literally at the epicenter of all things jungle-y. In less than five months he was the recipient of a couple experimental medications of clearly dubious efficacy that were–naturally!–immediately followed by a nasty bout of COVID-19, multiple bee, wasp and ant stings, one dangerously venomous coral snake near miss, and a full series of rabies shots that were the byproduct of rather unwisely free-handling a mastiff bat in a very bad mood.

That poor animal has not yet recovered from the trauma of chipping a small piece of snow white enamel off a canine while reducing the base of Fred’s thumb to steak tartare in the blink of an eye.

As the only guest in the small hotel where he stayed, he delved deep into his Alsatian upbringing and introduced yet another fusion element to an already rich and celebrated Peruvian cuisine. Who knows? Perhaps years down the road the fantastic Chinese-Peruvian fusion called Chaufa will be displaced by delicacies such as Crêpe de Cassava avec Pirarocu and other dishes that will define Alsace en la Selva. And while Fred was transforming the palate of at least one lucky Peruvian family, even if only to fight off boredom and isolation, he surely developed an audience that will miss spaetzles, savory pies and other culinary goodies otherwise hard to come by while trapped in the middle of a global pandemic in a scenic Interandean valley.

A magical rainforest understory in Tingo María filled with the popular tropical foliage selection, seersucker plants (Geogenanthus poeppigii). Image: ©F. Muller 2020.

The travel ban ends when?

Tingo María is currently under very strict curfew and has been since mid-March, meaning that no civilians can move around the city or public roads without permission between 2000 hrs. to 0500 hrs. Fred, apparently with ice cold Pisco running through his veins, and having previously obtained authorization from a local university botany professor to document local flora and fauna through images, spent many of his nights wandering Tingo Maria’s several beautiful forest reserves during those hours, returning to sleep during the day. Local park guards spoke of hearing coyotes howling at night while Fred roamed these lonely forest paths with only his camera for company.

But there are no coyotes in Perú. It was just Fred.

He was well and truly homesick. And when he is especially homesick, he likes to sing.

In French.

Joking aside, among other pursuits Fred is an avid amateur herpetologist who loves to spend his long nights alone looking for rare reptiles and amphibians to photograph. But the Mother of all Nature, Gaia (occasionally referred to in less charitable terms by those caught under her oft-heavy foot), was not especially kind to him in Tingo María. Dishing up decidedly fewer herps than one would reasonably expect in a megadiversity locality like Tingo, she’s mainly served up insects and other arthropods for his viewing pleasure. Stoically, Fred decided that rather than getting upset, he would get even and rustle up a collection of closeup images of his new-found love: bichitos (a generic Spanish term for all manner of tiny critters).

He also planned a few nights off to cook up some new recipes at the hotel and maybe watch a little TV Channel 113, the Jungle Channel, that will be airing a brand-new sitcom called “Gilligan’s Island”.

It’s supposed to be a hoot.

Some notes on Fred’s technique

Having spent decades photographing plants and wildlife around the world, Fred Muller has reduced his gear to a lightweight minimum, something you learn to do after thousands of hours photographing natural history subjects in remote areas.

He uses a Nikon D750 with a 100 mm macro and ring mount around the lens that holds two small flash units with diffusers.

Like many other professional nature photographers, over time his equipment acquires the Bride-of-Frankenstein look, adorned with scars, stickers and reminders of field repair jobs and modifications (a.k.a. duct tape engineering) visible all over. This has allowed him to find a combination that produces very natural looking images, always slightly asymmetrically lit, with good color saturation. Learning flash photography normally progresses from rejection, based in ignorance - to euphoria, based on studio-like results - to moderation, based on experience. Fred’s images show the balance of long-time field experience. He also explores his subjects until exhausting all their visual possibilities. That´s how he has discovered some unexpected life forms in his collections.

Velvet ant (Hoplomutilla sp.), Tingo María, Perú. Image: F,. Muller.

One beauty was the native velvet ant (Mutillidae: Hoplomutilla species) shown right. Velvet ants are actually parasitoid wasps that are generally aposematically colored and may mimic ants as protection from predators. Females are wingless, solitary and conspicuous, but males are winged and less commonly observed. They deliver a wildly painful sting – they are sometimes known as “cow killers” in the ‘States and are known as “the ant that makes you cry” in Quechua - so this makes one wonder why they bother at all with ant mimicry?

In an even more mind-boggling example of the Triple-Dog-Dare of insect mimicry: there are winged spider wasps (Psorthaspis species) that mimic velvet ants, that are wasps that mimics ants. See image below. They can fly, they can bite and they can sting like a SOB.

While everyone can understand the frustration that Fred’s circumstances generates, there are infinitely worse places for a nature photographer to be stranded than Tingo Maria, Perú.

We believe that once the current Mayor finds his keychain, he will gladly hand the keys to the city to Fred. Then Fred will run for Mayor and win by a landslide under the “Alsace en la Selva” ticket.

Otherwise, we hope to Christ he can get home soon.

I have taken the liberty of choosing what I think are some of his nicer close up images of Tingo María’s amazing arthropod fauna. Please bear with me as I work through identifications of some of these rather poorly-known animals.

All images ©Fred Muller 2020.

May I suck your blood? A harmless - to humans - but forbidding-looking Peruvian shield mantis, Choeradodis rhombicollis. Image: ©F. Muller 2020.

Katydids or bush crickets (Tettigoniidae) are famed for their incredible leaf mimicry. This one has faux lichens stencilled on its wing cases. Image: ©F. Muller 2020.

A female bullet ant, Dinoponera gigantea, one of the world’s largest ant species to 1.6”/4 cm long. Known as Isula in Perú, this is one of the large Neotropical ants famed for the ferocity of their stings, which are ranked at the very top (4) of Schmidt’s scale for measuring the pain produced by different insect stings. Image: ©F. Muller 2020.

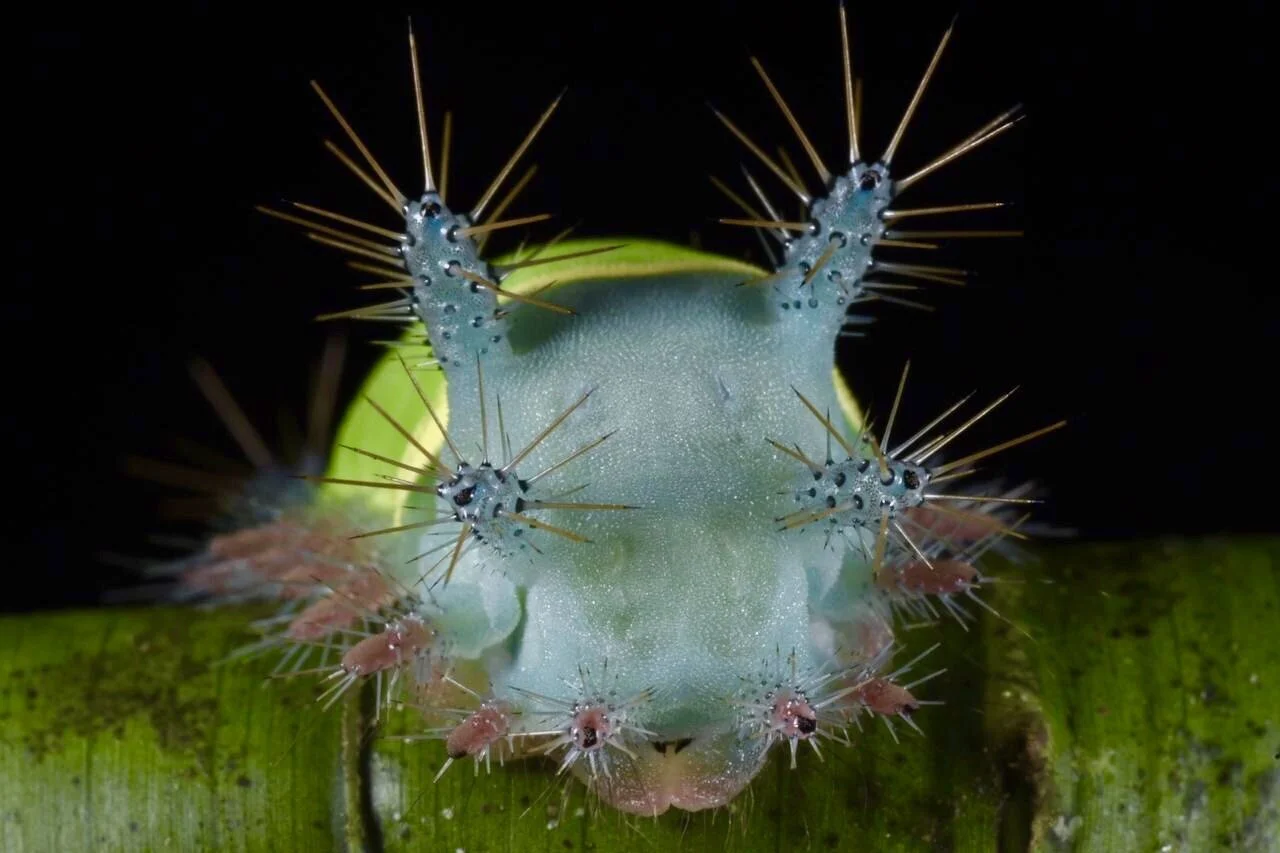

Fred has recently taken a particular interest in butterfly and moth larva with strange ornamentations and venomous spines. Below and right, a gallery of bizarre-looking and beautiful caterpillars found in his neighborhood that range from the alien to creatures that would seem more at home on a tropical coral reef.

By and large, anything shown here that is particularly thorny or hirsute will produce a painful sting or burning itch if touched.

Leafhoppers (Cicadellidae) are another very species diverse insect group (~20,000 described taxa worldwide) in the Tingo María area. The color schemes on some of these minute insects - which are generally 0.25”/6 mm or less in total length but do grow larger - are straight out of the Psychedelic Sixties.

¿Why would anyone be interested in an insect group as ubiquitous yet obscure as leafhoppers?

Well, for starters, this is one the largest families of true bugs (Hemiptera) with thousands of species that are not only important keystone “land plankton” in the trophic chain, but also significant agricultural crop pests and plant viral vectors in some cases.

Biologists from the Gilligan’s Island demo that took at least an introductory course of Entomology at school probably used Borror, DeLong & Triplehorn’s, “Introduction to the Study of Insects” (first edition 1954). This book is to insects what Peterson’s “A Field Guide to the Birds” (first edition 1934) is to U.S. avifauna.

Dwight DeLong passed away in 1984, leaving a legacy of nearly 400 peer-reviewed papers on leafhoppers. They come in all colors and patterns and flavors; it is fairly common in the American tropics to find a dozen or more species on a single host plant. When I read articles that attempt to quantify biodiversity based on biological inventories, they usually start with everything we think we know (e.g. large vertebrates, trees, orchids), move on to other life forms we admit we don’t know much about (e.g. slime molds, mycorrhizas, tardigrades), then conclude with creatures we’d rather not know at all (e.g. viruses, reggaeton singers, politicians, headlice).

Contemporary biological diversity researchers all come to the same conclusion: our living planet is far more biodiverse than we ever thought, and we are losing this diversity much faster than we ever thought possible.

Leafhoppers demonstrate this point in a small and often colorful way. And their allure, such as it is, is based not only on the wealth of patterns and shapes of these tiny invertebrates, but also on the fact that for such a diversity of species to coexist, the web of life must be a complex and wonderful thing.

Both of us (PR & JV) are of the school that taught us you best change human perceptions about snakes one person at a time. This Peruvian rainbow boa (Epicrates cenchria) was waylaid while wandering the hotel garden. After a brief tutorial on safe handling by Fred, this charming nine year-old Peruana discovered that most snakes–but especially Peruvian rainbow boas–are beautiful, fairly docile and retiring creatures.

Shown below after relocation to a slightly safer spot for snakes in the neighborhood.

Peruvian rainbow boa (Epicrates cenchria) in nature. Image: ©fred Muller 2020.

Extreme closeup of wing of the blue-banded Morpho butterfly, Morpho achilles, Image: F. Muller.

Collared tree runner (Plica plica). Image: ©F. Muller 2020.

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC® 2020-2025, ©Peter Rockstroh 2020, ©Fred Muller 2020, and ©CBS Broadcasting Inc.

Follow us on: