Ridley's Staghorn Fern - Platycerium ridleyi

by Jay Vannini

A beautifully-grown group of mature Platycerium ridleyi displayed as lateral mounts on treefern slabs at Purificación Orchids, Quezon City, Philippines. Image: R. Parsons.

Among the world's most spectacular epiphytes, this high canopy antfern is also an unmistakable standout in a genus known for its many attractive and striking species. On the Asian mainland Platycerium ridleyi is now reportedly of very localized distribution in the lowlands of southeastern Myanmar (Burma), Peninsular Malaysia and its associated archipelagos, as well as the Chumphon Province in southern Thailand. Beyond the now fragmented mainland populations, it is also reported at widely-separated localities from lowland tropical forests of Brunei, Sarawak and East Kalimantan in Borneo (Tawan et al., 2004) as well as Aceh and Jambi Provinces in Sumatra (Franken & Roos, 1982). This staghorn has been considered locally extirpated in Singapore for many decades (Wee, 1984). Populations across its range have reportedly declined substantially over the past ~40 years due to habitat loss and uncontrolled wild collection.

This extraordinary epiphytic fern was first “discovered” by George Frederick Hose, the Anglican Bishop of Labuan and Sarawak around the turn of the last century. Hose was also an amateur naturalist and founding member and later president of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Sometime in 1898 he showed it to Sir Henry Ridley, then director of the local botanical garden and zoo, in what is now the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve in Singapore. More than a decade after its discovery, Ridley wrote, “Bishop Hose first pointed out this plant to me some years ago on perfectly inaccessible boughs of a lofty Shorea tree, 100 feet or more above the ground. There are a number of plants on the bough, all quite similar and there are no typical specimens of Platycerium biforme (an unresolved name, but here = P. coronarium) on the tree, though it is abundant in surrounding forests. I have only been able to obtain fallen fronds…The plant is most closely allied to P. biforme but I hardly think it can be classed as a mere form or state of that plant…On the same trees, which bears this curious fern, grows also Lecanopteris carnosa, the only lowland locality I know for this plant.”

Despite his correct initial conclusion that it must be a new species, Ridley opted to follow Kew fern specialist Charles Wright’s rather peculiar conclusion that it was just a “full sun” variety of what is now called Platycerium coronarium. Ridley published this species as P. bifurcatum var. erecta in 1908, and assigned a personal accession number to a type specimen that apparently persists in the Singapore Herbarium (Ridley SF 10830 - SING).

After this collection, this species has a rather convoluted taxonomic history indicative of a race among fern specialists for naming rights. Again in 1908 it was simultaneously described as Platycerium coronarium var. cucullatum by Dutch botanist Cornelis van Alderwerelt van Rosenburgh in “Malayan Ferns”, but without a type specimen or collector’s number (fide Flora Malesiana), so this name is clearly invalid. It was again (incompletely) described by the famous Swiss fern authority Konrad Hermann Christ as P. ridleyi two years later (but in a paper submitted in 1909) in “Supplement 3, Partie 1 of the Annales du Jardin Botanique de Buitenzorg” (1910). Because of this sequence of events, but surprisingly nonetheless, the proper binomial for this amazing and popular staghorn fern is still unresolved; P. ridleyi appears to never have been validly published (Ridley, 1908; Christ, 1910; The Plant List 2019).

Presumably, prolonged use of Platycerium ridleyi Christ in horticulture and regional botanical texts will ultimately lead the IAPT to resolve in favor of the conserving this universally-used combination.

BUT…

..in my opinion, Platycerium erectum Ridley does seem to be the correct binomial. When the taxonomic dust finally settles, and even if it makes staghorn fern collectors cry out in anguish, this may be what we end up calling it. In either case, the common name, “Ridley’s staghorn fern” will likely prevail.

Together with another species that can be demanding in horticulture, Platycerium holltumii, this was the last staghorn fern species to be introduced to cultivation in the west. As recently as the mid-1970s, as knowledgeable an authority on cultivated tropical ornamental plants as Alfred Graf of “Exotica” fame referred to this species as P. “ridleyi” hort. and noted there were lingering questions as to the true identity of this species (Joe, 1964; Graf ,1974). Ironically, by that time P. ridleyi had found its way into limited cultivation in southern California, dispelling earlier concerns that it might be extinct (Hoshizaki, 1977).

Above, two nice frond forms of Platycerium ridleyi mounted on tree fern blocks being grown in California by the author (left) and Tom Perlite of Golden Gate Orchids (right). When established upright like this, these ferns will develop dramatic-looking, skirt-like shield fronds that drape down over the mount.

Despite its coveted status among rare plant collectors, Platycerium ridleyi remains somewhat uncommon in cultivation in the west, although imports have recently increased several-fold so availability (mostly in the form of small plants) is generally not an issue. Besides being a tad finicky in its needs, it does not offset and sporelings can be challenging to grow on from initial transplant. Some success has been achieved in both PTC and in vitro germination of spore in SE Asian laboratories over the past 20 years and increasing supplies of artificially-propagated young ferns are now entering the international market. Unfortunately, large numbers of wild-collected plants still find their way into both local and international trade, apparently from southern Myanmar and parts of Malaysia, even though consistent success re-establishing this material remains rather elusive.

Large numbers of recently-established Platycerium ridleyi, P. coronarium, P. elephantotis, P. stemaria and other staghorn ferns for sale at a nursery in Chiang Mai, Chiang Mai Province, northwestern Thailand during the winter of 2019. Note that most P. ridleyi here are mostly being grown upright in 10”/25 cm baskets, not as lateral mounts on cork or treefern slabs as shown in the opening image. Image: T. Nguyen.

A reporter writing in the Bangkok Post (“Orchids are born to be wild”, February 2012) following a visit to the Chatuchak Market in Bangkok observed:

“Many enthusiastic plant lovers travel the 300 km or so from Bangkok to Dan Singkhon to find rare plants brought into Thailand from Myanmar's Tanao Sri mountains. These include not only orchids but ferns like the Platycerium ridleyi, known in Thai as khao kwang bai tang, which used to be plentiful in Phang Nga but are now extinct in the wild.

Two young mature Platycerium ridleyi of a narrow lobed frond form reminiscent of Burmese origin material in a mixed planting on a cork tube with Paraphalaenopsis labukensis in the author’s California collection.

One of the most beautiful forms of staghorn ferns, distinguished by its slightly lobed shield fronds which are patterned by raised veins with sunken areas in between, and by its erect fertile fronds that fork many times, Platycerium ridleyi can be found on the Myanmar side of the border but relentless collecting could render it extinct there, too…”

The trade in wild Burmese staghorns is not a recent development. The late, well-regarded and very knowledgeable Thai rare plant grower Chanin Thorut uploaded an image taken in 2006 to an internet garden site of large, wild-collected Platycerium ridleyi and P. coronarium piled on the ground at the border crossing mentioned above. As of June 2018, wild-collected mature Burmese P. ridleyi were still being openly offered online in Japan and in December 2019, obviously wild collected ferns of recent vintage were seen for sale at Chatuchak Plant and Flower market in Bangkok, Thailand by an acquaintance (T. Nguyen, pers. comm.).

On the bright side, improved supply of spore-grown Asian plants now available in the US and EU over the past several years has translated into prices for smaller plants dropping to levels where they are generally more affordable to the average rare plant grower (~USD 50.00-100.00). Nonetheless, well-established specimen-sized plants remain quite costly in the horticultural trade, with prices commonly running into the hundreds of USD/EUR per plant at specialty nurseries in the EU and U.S.

Wherever possible, newly-minted staghorn growers in the U.S. and EU should try and purchase well-established plants of this species despite their higher price. Bare-root imports – while relatively inexpensive - may prove very difficult for novices to re-establish without bright, warm mist benches or high-humidity/well-ventilated tropical growing environments. They may also require frequent “touch-ups” with fungicides at the beginning to arrest localized leaf rot that is the byproduct of rough handling and dehydration during transit and inspection. My personal experience indicates that turnaround time from wilted young import to salable specimen plant in the U.S. is just over a year under near optimal conditions. Caveat emptor: for most amateur growers, this “turnaround” never occurs.

A pair of Platycerium ridleyi shown together with flowering Bulbophyllum medusae on a cork tube mount in the author’s California collection. Image: R. Parsons.

I have found that success with this species hinges largely on cultivation in an environment that provides constant warmth, consistently high light intensity coupled with excellent (gentle to moderate) ventilation at all times, good water quality and a steady feed of low-dose fertilizer with a skew towards higher N available in non-urea form. Please note that most knowledgeable growers emphasize the danger posed by keeping larger specimens permanently wet and the need for good air movement around them. Fully mature specimens MUST be allowed to dry out a bit from time to time and should be kept where air circulation is good. While this is a lowland tropical fern, I have observed that - once well-established - it also survived conservatory conditions in central Guatemala that regularly experienced brief night-time drops into the 48-50 F/9-10 C range, and in California to a few degrees F higher during the winter with no visible damage. In contrast to Platycerium madagascariense, P. ridleyi can tolerate fairly lengthy periods of its root ball drying to just barely moist, although some frond wilt and tip burn may be evident following a prolonged drought. Note that total desiccation for any period beyond a few hours may kill the plant outright. I prefer to keep them evenly moist while their fronds are developing, then letting them dry out to slightly moist to the touch between watering during the cooler months after the newest fronds have fully-expanded and hardened off. They can certainly take a lot of water in the summer when kept bright and airy. Needless to say, their preferred temperature and humidity ranges are both high and the finest specimens are grown in under those conditions in the well-illuminated upper parts of greenhouses.

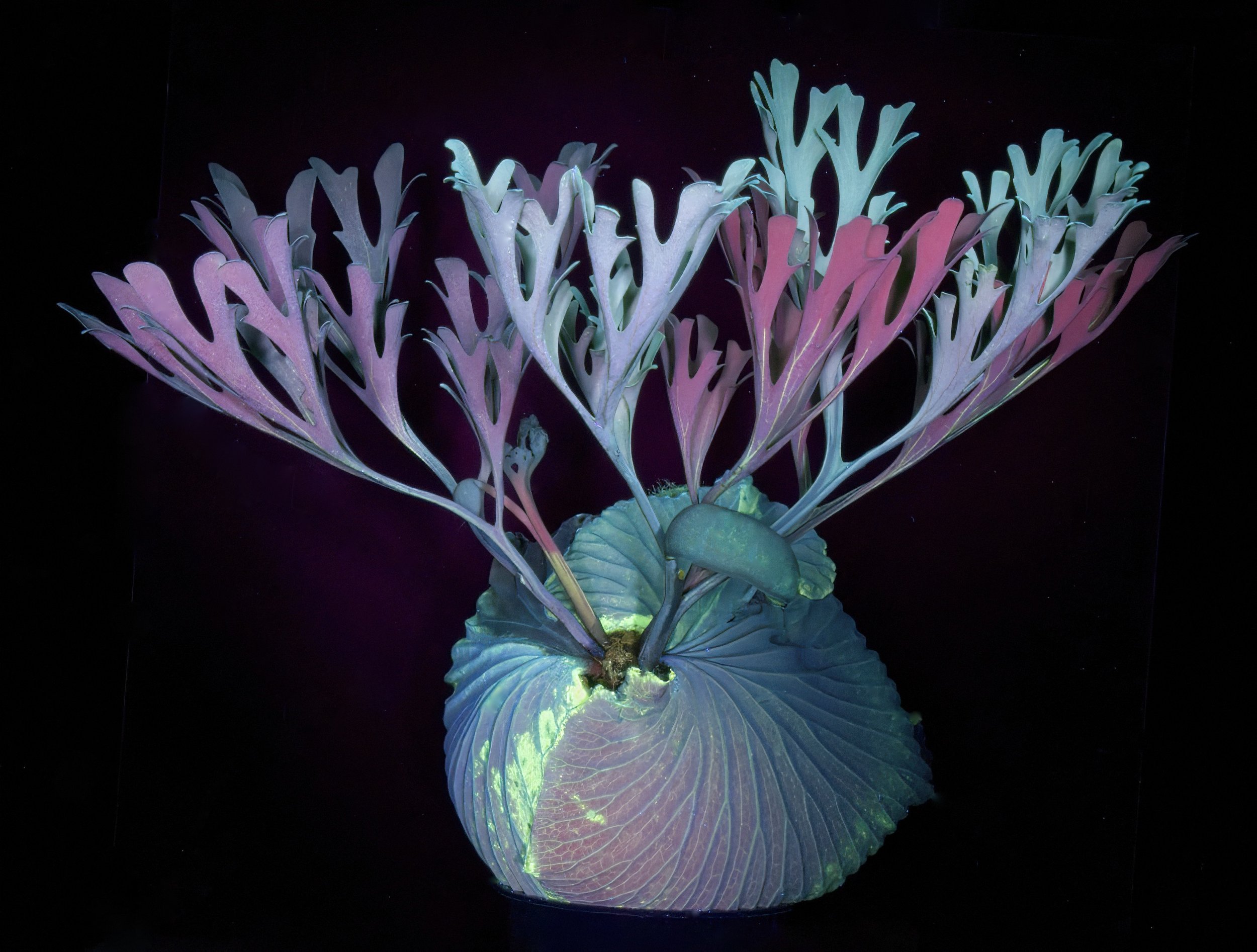

Like other tropical fern species popular in cultivation, Platycerium ridleyi exhibits showy, polychromatic fluorescence when illuminated with longwave ultraviolet light. The pale blue areas show where the fronds are partially shielded from excess sunlight by cuticular wax coatings. More information on UV fluorescence in ornamental plants may be found in another article on the website, here: https://www.exoticaesoterica.com/magazine/plantuvfluorescence

Author’s plant and image.

The plants shown here were mostly grown on from 10-12 cm diameter artificially-propagated plantlets acquired from a variety of sources (Singapore, the U.S., Thailand and Taiwan) from early 2009 in Guatemala and late 2017 onwards in California. For size reference, the fertile frond span in the larger of the two Guatemalan plants shown in 2012 is ~85 cm. This individual was very vigorous at this stage of its development and is pushing two new fertile fronds in this image. Despite some reports, I have not found this species to be slow-growing under warm, humid greenhouse conditions; quite the contrary.

Cutaway showing details of a young Platycerium ridleyi root system within nest fronds. Growing tip with new leaf forming visible upper left edge.

Suitable mounts include cork flats and tubes, treefern flats, rounds and log sections, as well as hardwood plaques with a hole cut in the back to permit root ball drying. Some growers have grown them successfully in large clay pots or bowls, where the effect can be especially dramatic when the shield fronds on mature plants sweep down over the edges of the pot like a ballroom gown. While into the recent past I preferred to use large cork plaques or tubes as mounts for my own plants, I now favor planting them on the tops of tree fern log sections, of 10-12”/25-30 cm in height and 9-10”/23-25 cm diameter. Based on recent experience with a fairly large group of medium-sized imports, it seems that plants establish far more rapidly and achieve more natural form when planted upright. I have also seen beautiful specimens cultivated essentially as twig epiphytes on narrow diameter cork tubes and grapewood. Over the past year I finished mounting several of these ferns on 20-24”/50-60 cm long cork tubes already colonized by the showy-flowered Malesian orchids, Bulbophyllum medusae and a small Paraphalaenopsis labukensis. Images of these large “epiphyte sticks” are shown here.

After a decade or more from spore these plants can attain impressive dimensions when well-grown in optimal environmental conditions. Reports and images indicate that the fertile fronds on some very large wild plants may exceed 3.5’/1.10 m in diameter.

The quality and vigor of cultivated plants, as evinced by images on the internet and recent purchases of fair number of artificially-propagated imports, has improved markedly over the past decade. As is the case with other sometimes ‘touchy” staghorn ferns such as Platycerium madagascariense, P. ellisii, P. quadridichotomum and P. wallichii, this improvement in plant material often marks the difference between success or failure with this plant.

It is interesting that two of the three Platycerium species that are myrmecophytic share similar nest/shield frond morphology despite not being very closely related. Both Platycerium ridleyi and P. madagascariense have handsome, fully enclosed, globular nest fronds that do not function as litter traps like their larger cogeners. The elevated main veins impart a distinctive scalloped or channeled aspect to these fronds, and their raised design is presumably to facilitate movement of ants throughout the root ball. This staghorn appears to be unique in the genus in having "pores" (see second image below) evident on larger nest fronds, perhaps to facilitate entry and egress of small ants to the root mass. Its very close relative, P. coronarium, is also commonly colonized by ants and termites. They share several characteristics, including uniquely-shaped sporal branches/spore-bearing fronds and a reduced number of spores (eight) within their relatively small sporangia (Kreier & Schneider, 2006).

The distinctive “scoop”-shaped sporophyll of a young mature Platycerium ridleyi branching from the base of a fertile frond. Author’s collection.

The sporangia of Platycerium ridleyi are located on specialized, spatulate-shaped extensions that are an appendage on the lower parts of larger fertile fronds. In some large specimens these can become hemispherical or near-globular in shape and resemble round ice cream scoops. Despite their size and lower spore count when compared to other members of the genus, this species can still produce copious amounts of spore when fully mature and well-grown. Unlike many other species in the genus, spore casings “froth” conspicuously when dried over a source of gentle warmth.

For many years it was rumored among fern growers that this species was almost impossible to grow from spore outside of the laboratory, and required very specific media to reproduce. Besides my own limited success propagating them from spore, a friend in Guatemala who ended up with my staghorn fern collection there was successful in producing very large numbers of small sporophytes of Platycerium ridleyi from spore sowed on sterilized, shredded tree fern fiber, but lost them at an early development stage to fungal blight due to overwatering. My first batch of well-developed sporelings were cooked to death when accidentally exposed to a few hours of sunlight in an enclosed plastic container. I currently have large numbers of spore sown material from late 2019 growing in California under sterile conditions. Other growers outside of Asia have successfully produced small numbers of plants from spore on media like sterilized coir, and it seems a given that more of these plants will appear on the market in the next few years.

In my experience, fresh spore from mature plants germinates readily on suitable - preferably sterile - substrates within 45 days under warm greenhouse conditions. Comments by the few fern growers who have succeeded in propagating this species from spore outside of Asia indicate that scrupulous hygiene and attention to detail is critical in taking this species from spore stage to fully exposed community trays of young ferns.

Ridley’s staghorn is reported to occur sympatrically with the widespread, giant Platycerium coronarium at many localities across its range although not known to occur on the same host trees. Platycerium ridleyi is reported as being restricted to the exposed branches of the brightly lit upper canopy of emergent trees, often in swamp or heath forest. It can be colonial and occur in groups of over a dozen mature individuals (Franken and Roos 1982). See this link to a stunning image captured by regional natural history photographer Ch’ien Lee in Sarawak for one illustrative example (clicking on this link will take you offsite - use your back button to return to this article): https://www.mindenpictures.com/search/preview/staghorn-fern-platycerium-ridleyi-group-on-tree-sarawak-borneo-malaysia/0_00559827.html .

In contrast, Platycerium coronarium usually occurs lower down in shadier conditions, often as a massive colony ringing the main trunk. Both species are known to host ants, and are often found in association with Lecanopteris crustacea, another regional antfern that is popular with tropical plant collectors together with the adder’s tongue fern, Ophioglossum pendulum. I have not been able to confirm the existence of wild hybrids between these two staghorn ferns where they occur together despite hybrids rather commonly surfacing in cultivation when they are grown together under fully tropical conditions.

Because of its strong visual appeal, this fern has been hybridized - both intentionally and by accident - in Asia and the U.S. by several fern enthusiasts and nursery owners. A few of the, especially the ones involving Platycerium coronarium, are very popular in horticulture. Besides the hybrids listed here, others are currently in the works.

A young mature Platycerium Mt. Kitshakood, narrow leaf form in the author’s California collection. This hybrid is extremely variable depending on influence of the parent ferns.

Platycerium ridleyi hybrids available in early 2020 include: Mount Kitshakood (= x coronarium), x kitshakoodiense (same cross, better documented provenance), ‘Ployratana’ (F2 kitshakoodiense selfings), ‘Charles Alford’ (wandae x ridleyi), x stemaria, x alcicorne, x grande (“Grandeer”) and x quadridichotomum.

Khao Khitchakut (Anglicized = “Kitshakood”) a site in central Chanthaburi Province, Thailand is the locality alluded to by the hybrid name Platycerium Mt. Kitshakood. It is located in the District of the same name and houses a national park and is the area where many very well-known Thai fern growers and nurseries are located. Thai sources now offer a wide variety of Kitshakood leaf forms, with the “narrow form” and its spidery fertile fronds being one of the most attractive and unusual-looking as shown above.

Young mature Platycerium x kitshakoodiense ‘Ployratana F2’ in the author’s collection, measuring 42”/1.08 m across and flanked by young P. ridleyi mounts in the background. Note the upright shield fronds that this hybrid inherits from P. coronarium. Fully mature examples of the better Ployratana clones can span 6’/1.85 m across and are one of the most attractive hybrid staghorns. As is evident in this image, they require fairly high light levels and a well-ventilated environment to thrive.

Besides primary hybrids, there appear to be specific ecotypes from different parts of its range that are recognized by Thai and other southeast Asian growers, as well as induced mutations and artificial selection for certain frond types, particularly extremely narrow or very wide forms. Some particularly attractive forms that I grow have thin frond bases and upright, repeatedly-forked fertile fronds. Others have broad, bluntly-lobed fertile fronds resembling large elkhorn corals (Acropora palmata). Some of the more unusual forms offered by Thai and Taiwanese nurseries (current January 2020), with most names more or less self-explanatory, include: “Long frond”, “Wide frond”, “Crest”, “Round frond”, “Special frond”, “Sweet heart”, “Cloud” and “Narrow stem Myanmar”. Many of these select forms are now in PTC in Asia as well as from spore grown series.

Variant frond forms of two young Platycerium ridleyi “Cloud”, an unusual Taiwanese selection imported by a friend. Photographed at Golden Gate Orchids.

U.S. and EU fern collectors should note that some of the younger so-called “wide leaf” forms sold by domestic nurseries can be very different looking creatures as adults than those being cultivated and sold in tropical Asia.

A young leaf on the wide form of Platycerium ridleyi.

New growth is very attractive to snails and slugs. Safeguard accordingly. Mealybugs and aphids are annoyingly frequent and persistent pests of all staghorn ferns but respond well to treatments with most “soft” insecticides. Note: do not allow the growing tip on this fern succumb to rot or pest damage - you will lose the plant in short order if you do.

High magnification image of mixed prothalli and young sporophytes (note tiny fronds) of Platycerium ridleyi grown on an organic substrate by the author in California.

Due to the ongoing efforts being made by some Thai and Taiwanese nurseries to substitute wild-collected Platycerium ridleyi for propagated material of easier-grown, selected forms, as well as a few very attractive hybrids being made with it as a parent, I highly recommend that anyone who can avail themselves of the right conditions to try their hand at growing these very rewarding antferns. There are also U.S. nurseries that have produced limited numbers of spore grown plants in the past, with significantly higher numbers of domestically produced staghorn ferns of all species expected to become available in coming years.

Tom Perlite’s magnificent young Platycerium ridleyi “Cloud” growing in his San Francisco nursery, Golden Gate Orchids. This very unusual leaf form can produce very desirable specimen plants when grown upright like this. Together with the very elegant-looking spidery-frond wild varieties purportedly originating from eastern Myanmar, this is the leaf form I find most attractive.

Acknowledgements

A special thanks to Tom Perlite of Golden Gate Orchids for graciously helping me access a number of the newer plants shown here, as well as permission to photograph several of the exceptional plants in his personal collection. I’d also like to thank two anonymous acquaintances who shared their recent experiences and looks at many copyrighted images of this species being cultivated at tropical Asian nurseries. I am also grateful to Tuan Nguyen for his valuable observations on both the species in nature in Sarawak and on Wardian case cultivation of a mature specimen in California, as well the image of the Thai fern shop shown here. As always, I’m indebted to Ron Parsons for sharing his fantastic group portrait of Platycerium ridleyi at Purificación Orchids in the Philippines that is shown at the top of this article as well as the image above of my Bulbophyllum medusae mount taken last fall.

A bench of young mature imported Platycerium ridleyi mounted on treefern blocks being acclimated at Golden Gate Orchids, San Francisco, California. Several distinctive leaf forms are represented. Near optimal conditions are required to succeed with imported P. ridleyi and total losses by novices are the general rule.

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC® 2020-2025 and ©Ron Parsons 2020

Follow us on: