Stained Glass Palms

If you’re a rare palm aficionado, an invitation to a hot date with the divas

by Jay Vannini

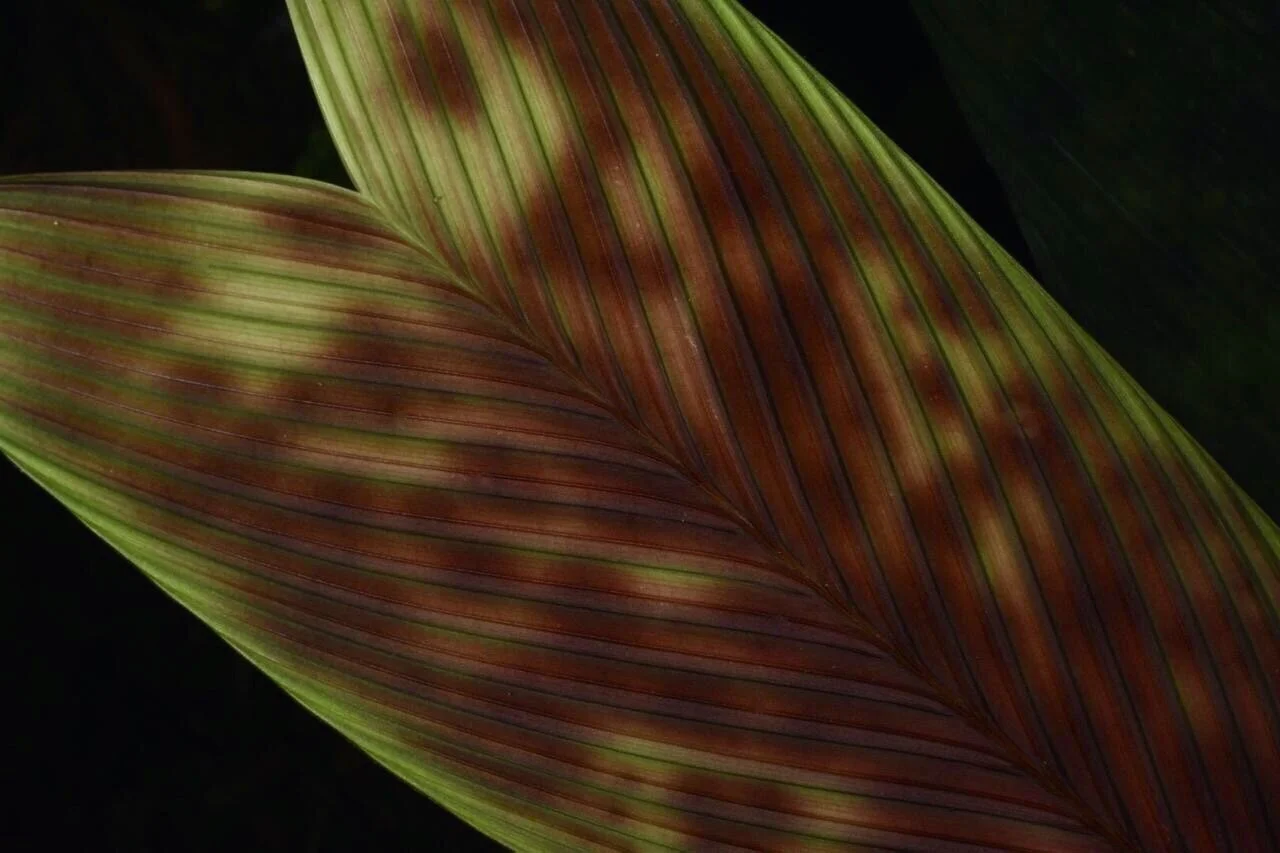

Newly expanded leaf on an eastern Panamanian Geonoma epetiolata in nature. Image: F. Muller.

Palms with red emergent and/or strongly mottled green and black leaves are prized by ornamental plant collectors because of the bold and colorful impression that these plants make in tropical gardens and greenhouses. Several species of uncommon to very rare shade dependent palms are especially remarkable and desirable due to their very strikingly patterned new frond flushes which, when backlit, are reminiscent of stained glass windows.

Above left, backlit mature leaf detail (lower leaf surface) on a cultivated Calyptrocalyx leptostachys, author’s collection and image. Right, backlit emerging leaf detail (upper leaf surface) on a wild Costa Rican Geonoma epetiolata. Image F. Muller.

The miniature, simple leaf form of Geonoma monospatha occurs in sympatry with G. epetiolata in Veraguas Province, Panamá and is closely related to both that species and G. hugonis. This, like its sibling species from premontane and lower montane forests, is challenging and rare in cultivation. Image: F. Muller.

Few palm species exhibit these attractive qualities quite like several species of fairly small sized understory Neotropical and New Guinea palms of the genera Geonoma and Calyptrocalyx. First introduced to horticulture at the beginning of the last century, they remained mostly a mystery to foreign botanists and palm growers until the 2000s. Starting in the 1980s in New Guinea and again around 2000 in Costa Rica and Panamá, collectors began to transport small amounts of live plant material and seed to palm growers in the U.S., Australia and Asia. Despite offerings by specialty seed vendors over the past decade, and with two exceptions, these palms remain extremely rare in collections and have largely defied most growers’ attempts at successful cultivation.

I am fortunate in having had fairly steady access to freshly harvested, artificially propagated seed of a number of these species starting around 2005. After years of experimenting with different cultivation regimens in Central America and the U.S., I have been able to build a small collection of all of the palms shown in this article in California as well as having successfully flowered four of them in a greenhouse here.

A lightly mottled form of the widespread and extremely variable Geonoma cuneata in western Colombian lowland pluvial forest. This rather confusing species has several subspecies and local ecotypes that vary markedly in size, leaf morphology, inflorescence structure and preferred habitat. Image: F. Muller.

I’ll start with a caveat to most would-be collectors who seek bragging rights; unless you are experienced in successfully growing finicky Neotropical and Malesian undercanopy palms, have pure irrigation water and a shady, environmentally controlled growing space, these plants are not good subjects for cultivation. None of these palms are really suitable for tyros. As far as I am aware, almost every attempt to establish Geonoma epetiolata and G. hugonis over the past ~20 years by growers located outside of Hawaii, Guatemala and Queensland, Australia have almost all failed. Seedling plants are particularly prone to declining practically overnight for no apparent reason, so particular care should be exercised with them until they are at least three years old. The Calyptrocalyx species discussed here are generally far more amenable to cultivation and are also much easier to obtain than the southern Central American species but two can also be a bit quirky and rather slow growing in captivity. The best option among them for those who haven’t grown dwarf palms before are standard color phase C. pachystachys, which has the added benefit of being the most commonly available and least expensive species of this group.

An excellent option for collectors interested in trying their hand at undercanopy Geonoma species is G. atrovirens from southwestern Colombia and northern Ecuador This, one of the world’s most beautiful small palms and also among the darkest colored, is now well-established in cultivation with artificially propagated seedlings available from several commercial sources around the world. While by no means an easy to grow palm, it is a useful species to introduce interested growers to some of the quirks of other dwarf geonomas. There remains a question as to its correct binomial; while palm collectors have ignored this determination for the most part, Andrew Henderson (2011) and Plants of the World Online–formerly The Plant List–consider this a morphotype/synonym of the widespread G. macrostachys.

Above, two fairly easily-grown lowland tropical palms that offer unusual leaf colors and shapes to the collector. Left, high color variant of Pinanga disticha. Image: C. Hall & A. Dearden. Right, a seed grown, newly mature Geonoma atrovirens in the author’s collection in California.

Newly emerged leaf on a nice form of Calyptrocalyx pachystachys in a private collection in Queensland, Australia. Image: C. Hall & A. Dearden.

Another great choice for those interested in growing a fairly easy mottled leaf palm are the high color clones of Pinanga disticha from Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia and Sumatra. The beautiful, very boldly marked examples from eastern Malaysia are also referred to as the “stained glass” form. These high color ecotypes are available in small quantities on a sporadic basis from nurseries specializing in rare palms. Pinanga disticha begins to cluster in youth and can be reasonably fast-growing under fully tropical cond

The five species discussed below have red, pink or orange emergent leaves with varying degrees of darker colored mottling evident as the leaves expand. Most retain some evidence of mottling on foliage throughout their lives, albeit in the form of very fine reticulation on the leaves of two of the Calyptrocalyx species.

The current general consensus appears to be that mottled leaf palms probably benefit both from reduced herbivory due to camouflage and that the darker leaf colors facilitate the capture of certain light spectra in their very shady forest floor habitats. No matter what individual genus or species you favor, they are all exceptionally attractive plants.

All images shown here and not attributed to specific photographers are protected under the author’s copyright. Other images shown here that were provided by Fred Muller and Chris Hall & Arden Dearden of Equatorial Exotics are covered under Exotica Esoterica LLC® and their copyright protections. Do not reproduce images shown here without their owners’ authorization.

And so, to the divas…

Geonoma epetiolata H.E. Moore 1980. Undoubtedly the most beautiful of all small palms, this species is generally encountered with a thin, solitary stem to ~3’/1 m although occasionally offsetting and to >10’/3.10 m tall. Occurring at ~325’/100 m to over 3,900’/1,200 masl in shady habitats in lowland tropical to foothill rainforests discontinuously throughout its range from the Caribbean versant in northeastern Costa Rica to low Continental Divide and Caribbean versant wet forests in central Panamá. The type material was discovered at Dos Bocas del Río Calovébora (now known as Río Dos Bocas) northwest of Santa Fé, Veraguas in western Panamá at ~1,600’/500 masl and collected by (who else?) indefatigable botanist Robert Dressler in 1974.

Secondary forest along a light gap in the Río Dos Bocas ravine in Veraguas, Panamá in October 2007. Areas adjacent to this type locality sheltered relict populations of Geonoma epetiolata when the photograph was taken by the author.

Over the past 15 years I have observed that some armchair/online “taxonomists” and palm collectors – many of whom have never seen the species in nature - have made a number of sweeping, incorrect generalizations about the ecology and cultivation of Geonoma epetiolata. One recurring but imprecise claim is that Costa Rica and Panamanian populations are readily distinguished by leaf color alone.

Above, two very large and very old Geonoma epetiolata in lowland Caribbean versant rainforest of central Costa Rica. Both palms shown are carrying immature fruits. Exceptionally large examples in this area may exceed the height of the palms shown here. Images: F. Muller.

A heavily-mottled mature example of Veraguan Geonoma epetiolata showing a backlit new leaf. Image: F. Muller.

A very dark leaf form of Geonoma epetiolata from the eastern extreme of its range in Panamá exhibiting only trace amounts of mottling. Image: F. Muller.

New York Botanical Garden-based palm specialist Andrew Henderson wrote in 2011 that four disjunct populations of Geonoma epetiolata show more or less consistent variation in floral characters and gross morphology. These are: (1) the Caribbean foothill Costa Rican (Heredia, Cartago and Limón Provinces) ecotype; (2) the El Copé, Coclé ecotype from PN Omar Torrijos and environs; (3) the Llano Grande, Coclé ecotype (presumably including those relict populations near El Valle de Antón and Cerro Campana) and; (4) the Colón Province and Guna Yala Comarca ecotypes from lower and middle elevations below and on Cerro Bruja and Cerro Brewster. Careful examination of live palms and images of living material from all of these localities indicates that this species can also show a surprising degree of variation within any given population. Generally speaking, the western populations in Costa Rican foothill rainforest tend to have much darker, often deep violet colored, concolorous leaves than palms from most the eastern localities. However, this is not entirely a reliable key character to distinguish cultivated plants of unknown origin, since some Veraguan and Guna Yala material can also have extremely dark colored foliage while the odd Costa Rican examples will have “blonde” new leaves. As far as I am aware, only the population occurring above Penonomé and El Copé, Coclé Province in central Panamá produces palms that will reliably flush ivory white and red-mottled emergent leaves. What the images included here do show is that this palm can be very variable in terms of leaf shape, color and pattern and, individual clones aside, these forms do suggest some correlation to specific origins or ecotypes as proposed by Henderson.

Above, from left to right and corresponding to western, central and eastern upland populations of Geonoma epetiolata in Veraguas and Coclé Provinces as well as Guna Yala Comarca showing color and leaf form variation in mature palms across key Panamanian populations occuring in protected areas. Images: (L and R): F. Muller, 2018-2019 and (C), 2005, the author.

The type of image that launched a thousand seed collecting trips to Costa Rica. Newly emerged leaf of a lowland Caribbean versant rainforest Geonoma epetiolata. Image: F. Muller.

This highly coveted palm has been subject to intense extraction pressure at known localities for almost two decades. Like another ornamental regional endemic palm, Chamaedorea sullivaniorum, Geonoma epetiolata was nearly extirpated near El Valle de Antón, Coclé Province by both U.S. “tourist” collectors in the early and mid-2000s and the Panamanians contracted by them who gathered them by the sack loads (M. Pérez pers. comm.; pers. obs.). Tragically but predictably, none of these many hundreds of illegally harvested plants survived outside of local hands for long. Accounts from correspondents in Panamá and the U.S. indicate that a fair number made it (barely) alive to Florida and California collectors and nurseries only to perish there shortly after import. The famous Costa Rican private ecolodge and forest reserve Rara Avis, located in Heredia Province, has reportedly suffered near constant pilferage of seed and plants ever since visiting nature photographers and birders posted images taken there of this palm online (IPS Palmtalk, 2009).

A very attractive example of the “white emergent” Copé form of Geonoma epetiolata growing trailside in Omar Torrijos National Park, Coclé Province, central Panamá in 2005. This individual palm, together with many others visible from public trails, were extracted between 2007 and 2008, presumably by poachers. This population has longer and far more glossy leaves than other well known populations in Panamá (see tryptych above).

In one of the first summaries of field studies of Geonoma epetiolata in Panamá, “The Stained Glass Palm”, Mario Blanco & Silvana Martén-Rodríguez (2007) noted unverified reports that the population around the type locality in Veraguas, Panamá had been extirpated. Subsequent observations by the author and others revealed this claim to be erroneous, although certainly the species is now very hard to find in that area. Ironically, promptly following their own publication in the journal “Palms” the conspicuous trailside plants in Omar Torrijos (also known as El Copé) National Park–a very vulnerable site revealed by Blanco & Martén-Rodríguez in their paper–were removed by poachers (pers. obs.). Further contributing to collecting pressure on the El Copé population, the Palmpedia website shows images of wild palms that were taken last decade, attributed to an EU based seed vendor and labelled, “Omar Torrijos National Park in Panama”. The sad reality is that, although this palm is incredibly challenging to grow and propagate and that the vast majority of wild collected material fails at germination level or promptly in cultivation as origin-source seedlings, visitors continue to extract wild seed and plants.

Despite concerns by conservation authorities that habitat loss and localized poaching may represent an short-term threat to the survival of wild populations of Geonoma epetiolata, this species is present in a number of parks and reserves in Costa Rica and Panamá. Recent observations at several populations across its range indicate that it remains locally common at remote, undisturbed sites that have not been publicized by botanists or visiting naturalists (F. Muller, pers. comm.).

Geonoma hugonis Grayum & de Nevers. This very small cloud forest species, a true elfin palm, grows mostly to about 24”/60 cm tall but exceptionally to almost 5’/1.50 m tall. It has a fairly narrow elevational distribution from ~3,600-5,200’/1,100-1,600 masl. Closely related to both G. epetiolata and rather less so to local populations of G. monospatha and G. cuneata, as well as G. brenesii from central Costa Rica, it possesses diagnostic reddish-brown scales on internodes and elongated petioles. Endemic and local at middle to upper elevations in Chiriquí and Bocas del Toro Provinces, Panamá, where it often occurs alongside the also rare and showy dwarf palm, Chamaedorea verecunda. The type material was collected by Hugh and Audrey Churchill near the Fortuna Dam in 1984. This is, by a wide margin, the rarest and smallest Geonoma species in cultivation and exists only in tiny numbers in a few collections worldwide. My limited personal experience growing it from seed indicates that plants cultivated under lights and mist in tall, ventilated terraria develop very short petioles and vivid leaf mottling and can strongly resemble G. epetiolata in youth. Unlike that species, which apparently offsets rarely and only after trunking, G. hugonis can begin offsetting when only three years-old and 12”/30 cm tall.

A fully mature Geonoma hugonis (R) alongside an adult Chamaedorea verecunda (L) in undisturbed cloud forest in the Fortuna reserve. Image: F. Muller.

A newly emerged leaf on a Geonoma hugonis on a misty day in Chiriquí wilderness. Cultivated plants tend to show very distinct leaf mottling when grown bright. Image: F. Muller.

A six year-old , seed grown Calyptrocalyx leptostachys from artificially propagated Australian stock in the author’s California collection.

Calyptrocalyx leptostachys Becc. 1905. This handsome palm species was first collected by Italian naturalist and ethnographer Lamberto Loria in 1890. To ~6.5’/2.0 m tall, it normally has simple then sometimes irregularly pinnate leaves when it develops a trunk. It has been erroneously (?) reported from the uplands of Central Province in southeastern Papua New Guinea. First collected in route “towards Mt. Yule”, an almost 8,800’/2,700 masl high forested peak, it almost certainly does not originate on the upper slopes of that mountain since it responds to cultivation as a tropical lowland, warm-growing palm. Despite its somewhat enigmatic origin, it has proven to be one of the easiest and rewarding Calyptrocalyx species to grow and propagate. There is quite a bit of individual variation evident in this species in cultivation, with some plants showing very deep orange or red emergent leaf color. This species is suitable for warm sunrooms and conservatories in temperate climates, but excels as a garden or shadehouse plant in the tropics.

A new leaf on a mature Calyptrocalyx leptostachys growing ina shadehouse in a private collection in Queensland, Australia. Image: C. Hall & A. Dearden.

Six year-old seed grown Calyptrocalyx micholitzii flowering in the author’s collection in California.

Calyptrocalyx micholitzii (Ridl.) Dowe & M.D. Ferrero. Another beautiful miniature New Guinea palm, mostly to ~3’/1.0 m tall. It was published in 1895 as a Linospadix species. Known from tropical rainforests at 975-2,600’/300-800 masl from northwestern Indonesia Papua in Fakfak, Paniai and Jayapura Divisions. This palm was first collected in 1891 by Wilhelm Micholitz, a German orchid collector employed by the English nursery Sander & Sons. Calyptrocalyx micholitzii was described by Singapore-based British naturalist Sir Henry Ridley Ridley from a specimen collected by Micholitz and given to him at an undisclosed date prior to its publication. Seeds were sent to Sander’s Nursery sometime after 1891, where a presumably seedling plant obtained by the Royal Botanical Garden at Kew in 1896 flowered in 1905. This was the first stained glass palm grown in cultivation and has been a coveted species for conservatories and warm interiors ever since. There is a particularly attractive form in cultivation known as “var. wilsonii”, first collected during an environmental impact study downstream of the Grasberg copper mine, located approxinately 60 miles/95 km NW of the coastal city of Timika. This improved form was then artificially propagated and distributed to Australian palm collectors by Greg Hambali a well-known Bogor, Indonesian plantsman. Plants now in cultivation have been line bred for several generations and can be quite distinctive. This selection generally has more intensely colored new leaves than the standard form occasionally offered by specialty U.S., and EU palm nurseries.

New leaf color on a mature, fruiting Calyptrocalyx micholitzii “var. wilsonii” in a private collection in Queensland, Australia. Image: C. Hall & A. Dearden.

Calyptrocalyx pachystachys Becc. This is mostly a small to medium sized palm to 5’/1.55 m, exceptionally to ~16’/5 m tall, and is widespread in both Indonesian Papua and Papua New Guinea across a wide variety of rainforest and cloud forest habitats from near sea level to ~4,900’/1,500 masl. The high color, mottled leaf forms, often with violet colored fruits, are Indonesian ecotypes and known by collectors there as Benang Daun Noda Noda (fide M. Pascall). Comments made by informed Australian palm growers indicate that this population may be elevated to full species status sometime in the near future. Originally collected by Friedrich Schlechter in 1902 in the Bismark Mountains of Madang Province, Papua New Guinea at ~4,900’/1,500 masl. Standard color forms of this species are occasionally offered as seedlings by specialty palm nurseries. While these forms will flush reddish new leaves, they will not exhibit anywhere near the degree of mottling shown here.

A very strikingly-colored new leaf on a young mature Calyptrocalyx pachystachys in a private garden in Queensland, Australia. Image: C. Hall & A. Dearden.

CULTIVATION

It should be fairly clear at this point that these are not particularly easy palms for most collectors to grow.

None of these species are suitable for long spells in warm, dry interior plantings. However, my experience over the past eight years indicates that all of them can be successfully grown until about 24”/60 cm tall by experts in high-tech, tall terraria/Wardian Case settings.

Optimal temperature and humidity ranges are more critical for success in Geonoma epetiolata and G. hugonis than for the Calyptrocalyx species. The oldest G. epetiolata seed accessions, both legal and a few that “fell into backpacks”, originated from the lowlands of central Costa Rica. These plants have proven to be far more warmth tolerant than the seed source populations that were available commercially for the past decade, all of which apparently originated from two cooler locations in central Panamá. These particular plants seem to do better under intermediate conditions with a nighttime temperature drop than those originating in the tropical rainforests below Braulio Carillo NP in Costa Rica. Geonoma hugonis is strictly a cloud forest palmlet and requires frequent watering or mist, high relative humidity and protection from prolonged exposure to daytime highs much above 80 F/27 C and nocturnal temps too much higher than 60 F/16 C. All three Calyptrocalyx species are fairly temperature tolerant in my experience but prefer warm, humid conditions between 80 and 92 F/27-33 C during the day with nighttime temps in the low to mid-60s F/17-18 C. They are also somewhat tolerant of short spells of dry conditions, although they may brown-tip if relative humidity is too low.

A pair of three year-old, seed grown Geonoma hugonis staged in 6”/15 cm plastic net baskets and cultivated in a cool greenhouse in the author’s collection in California. Their strong superficial resemblance to G. epetiolata when young is particularly evident here.

Undercanopy Geonoma species, especially those from cloud forests, are infamous for dying in captivity for no apparent reason after years of successful cultivation. And G. epetiolata is the undisputed Grand Champion of Sudden Death in this regard. Even very experienced growers have lost specimen sized examples of this species to fungal or bacterial infections over the course of their careers, so it is imperative to try and produce seed as soon as the plants are capable of carrying it to have backup stocks in case of catastrophic loss of founders.

Inflorescence emerging on an eight year-ol, artificially propagated Geonoma epetiolata in the author’s collection in California. A leaf has been removed to expose the spadix.

In the mid 1990s Silvana Martén and Mauricio Quesada conducted field research on the phenology and pollination biology of of Geonoma epetiolata in Braulio Carrillo National Park and the Rara Avis reserve in central Costa Rica (Martén & Quesada 2001). During the course of their work, they successfully hand pollinated flowers on a dozen individual palms to test and prove self compatability. Their published work contains a number of interesting conclusions - although they mistakenly concluded this species is incapable of asexual reproduction - and is definitely worth a read. Beside this successful human pollination of wild palms, as far as I can ascertain the first Geonoma epetiolata seed obtained from cultivated plants were produced in a private garden in the outskirts of El Valle de Antón, Panamá around 2004. Subsequently, very limited numbers of seed have been produced in a handful of private collections and commercial nurseries in Queensland, Australia and on the island of Hawaii. Very few private collectors and botanical gardens anywhere have grown G. epetiolata for any length of time, much less from seedling to maturity. One frequently mentioned is the Atlanta Botanical Garden which grew one during the 2000s. Cairns BG in Queensland, Australia briefly displayed a couple examples of this species about four or five years ago (where the display both mis-spelt “epitiolata” and gave an incorrect regional origin). Despite claims to the contrary by older palm nursery owners in south Florida, seed grown examples of this species from lowland Costa Rican ecotypes can – with proper care - succeed there in shade houses under mist with pure water and TLC.

My own experience is that cultivated Geonoma epetiolata begin flowering when eight or nine years old. This supports Blanco & Martén-Rodríguez’s statement that wild plants start flowering at about 10 years of age. Based on a very small sample size, G. hugonis begins flowering much earlier, apparently around four or five years of age. Flowers must be hand pollinated outside of their range states.

In contrast to the scarcity of reports of successful artificial production in the two Geonoma species, all three Calyptrocalyx species flower and fruit regularly in gardens and nurseries in Queensland, Australia, southeast Asia and Hawaii. Second and third generation seedlings are now available from all three sources.

Fresh seeds of all five species germinate promptly and seedlings can usually be transplanted between six and nine months after seed sow.

Above left, seven month-old artificially propagated Calyptrocalyx micholitzii recent transplants and right, one year-old seedlings of Geonoma epetiolata planted in 3.5”/9 cm pots in the author’s California collection.

With the possible exception of Calyptrocalyx leptostachys, all of these species – while usually considered solitary palms - are now known to offset or cluster; very rarely in the case of the two geonomas but rather commonly in older C. micholitzii and C. pachystachys. Care and planning are required when removing and attempting to re-establish offsets.

Two year-old seed grown, artificially propagated F1 Geonoma epetiolata from the Valle de Antón, Coclé, Panamá ecotype in the author’s collection in Guatemala.

Seedling Geonoma epetiolata shown above at four years in author’s collection in Guatemala.

Because of my overall collection’s high water requirements I favor sharply drained growing media for all of my palms. Because they are under mist as seedlings or subjected to almost daily overhead watering when on the bench, I also prefer hydro or net baskets to closed pots for species that resent perpetually saturated roots. Given their propensity for developing rots, I also have switched from pasteurized oak leaf mulch and pumice mixes that I used in Guatemala to fine NZ conifer bark and pumice + fluorite-based media in California. I incorporate generous amounts of balanced nutricote time release fertilizers, encapsulated gypsum and a very small amount of dolomite to these blends to compensate for the mineral free water that I use for irrigation in both terraria and greenhouse. While all of these palms resent excess fertilization, they will also decline rapidly when key elements, comprising both macro and micronutrients, are lacking. The best growing media will have a slight acid reaction and will last in good condition for years since all of these species resent root disturbance. Visitors to Hawaiian nurseries where several of these palm species are successfully grown and propagated will note that they are rooted into volcanic scoria and heavily top-dressed with prilled, time release fertilizers. As in almost all plants, focus on growing healthy root systems and the foliage will follow.

Supplemental iron, in small amounts and in chelated form, is useful to enhance the leaf color and mottling intensity of these palms. I have in the past relied on monthly drenches of water-soluble chelated iron derived from iron sulphate but have recently switched over to top dressing Ironite 1-0-1 due to its more convenient application. Do not over apply or problems will surely follow.

A pair of five year-old+, healthy F1 Geonoma epetiolata from the seedling batch shown above growing in a sheltered location of the author’s garden in Guatemala.

Prophylactic use of systemic fungicides to limit losses in these palms is a somewhat fraught subject these days, and the products that are most effective may be very difficult to obtain in some regions. I do employ them at concentrations and frequencies recommended on their labels but am sympathetic to growers who, knowing the risks to their plants, prefer to forego their use.

To those interested in other members of the palm genera discussed here I strongly recommend reading Henderson - “A revision of Geonoma (Arecaceae)” in Phytotaxa 17 (2011), which is an excellent and fairly current monograph, and Dowe & Ferrero, “Revision of Calyptrocalyx and the New Guinea species of Linospadix (Linopsadicinae: Arecoideae: Arecaceae)” in Blumea 46 (2001). Unfortunately, I can’t endorse any of the better-known books on ornamental palm horticulture since they mostly lack detailed information on these species.

Geonoma epetiolata from Veraguas Province, Panamá at sites located somewhat higher in elevation than the type locality often have very narrow-triangular leaves. Many plants in this region are also very vividly marked throughout their lives. Image: F. Muller.

Many thanks to my friends Fred Muller, Chris Hall and Arden Dearden for providing a large number of beautiful photographs for this article as well as their extremely valuable insights into the distributions, locations and variations of different populations of these rare palms. Chris and Arden are fortunate in having observed both of the Geonoma and some of the Calyptrocalyx species in nature in Costa Rica, Panamá and Papua New Guinea. They also sell artificially propagated stock of several palms shown here at their Redlynch, Queensland, Australia rare plant nursery, Equatorial Exotics. Interested buyers can reach them at: chris@equatorialexotics.com

Another very dark individual of Geonoma epetiolata shown in nature in central Panamá. Image: F. Muller.

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC® 2020, ©Fred Muller 2020, and ©Arden Dearden 2020

Follow us on: