El Manchón

by Jay Vannini

I awaken somewhere between whisky six and coffee one with the loud drone of twin Lycomings filtering through my window from out on the black sand runway behind the house. I slowly realize that one of those fast satellites that sometimes blink over the ocean has fallen from the night sky and materialized as an outlaw aircraft somewhere back in the mesquite after a ground-hugging, detection-free flight up from somewhere west of Cali, Colombia. The offload and refuel takes about fifteen minutes. There's a brief surge of engine noise, fading voices, and then it was probably never there at all. I close my eyes again and suspect that out near the five thousand-meter marker a pin-striped quarter ton of leatherback turtle has crawled from the surf to excavate a nest pit big enough to drop any random skanky politician into. I know that about twenty kilometers north of me a DEA Black Hawk loaded with some pretty sophisticated night vision gear and a few muscular but very quiet men is quartering the area between the volcanic piedmont and a tropical marsh like a high-tech predator in search of its psychoactive quarry. But I don't particularly worry too much about any of these things because in a few hours I will be mist-netting, leg-banding, and super-gluing micro transmitters on the carefully-plucked backs of painted buntings and yellow warblers down from the suburbs of Colorado and California, who have stumbled, quite literally, into our "tourist trap".

Then again, there's a fainter recollection of a real life that helps pay for all this: Twelve-month LIBOR is at six percent, local repos are near thirty, and regional Forex traders are taking the country's currency south faster than you can say, "hyperinflation". An old girlfriend seems to have lost an unhealthy amount of weight recently, my teenaged daughter is dating yet another obnoxious weirdo whose name I can't remember, and a new U.S. president is busy partying with Chuck Berry and Fleetwood Mac while parts of Baghdad burn.

The ghost of old man tiger pads warily to the edge of a Zapotón and palm hammock way back on the marsh, eyes the moonlit water around him for a moment with a cat’s fleeting interest, then dematerializes into darkness.

Camera-trapped Guatemalan wet forest jaguar out for a nocturnal ramble in the early 1990s. ©Peter Rockstroh 2020

While I wrestle with the need to disentangle myself from the mosquito netting and go take a piss.

°

There is this one locale where I once worked with a dusty obsidian mirror of an estuary hidden under old growth red mangrove canopy that towers a swear-to-Christ honest twenty-three meters over its surface. It is very still most times, broken only by the slow rolls of hungry gar that ease, like switchblades through molasses, from their submerged lairs to sip four-eyed fish from the many schools that mindlessly patrol the backwaters. There is a resident pair of ospreys tending a massive stick nest back in the storm-battered strand who stared haughtily down their beaks at me when I passed underneath them in a dugout, bound for the flooded pampas. Much like young media stars that have been lured by fawning critics into believing that they have talent, and ergo, are entitled to a surly attitude, these ospreys appear to shun paparazzi. For, when you stop and attempt to Kodachrome them, they will shout abuse at you and flee rapidly down the channel. They share the area with another nesting pair and thirty or forty migrant cousins that come for the winter sun.

They all appear to favor catfish for breakfast.

We had a wary adolescent spiny-tailed iguana who resided in the roof that was never quite certain as to our intentions towards him. A trio of witless blonde fox geckos hid behind my pictures on the wall, whose grandparents most probably hitched a ride to this sand-spit on a Taiwanese freighter.

They all somehow managed to survive our frequent use of residual pesticides around the house.

At dawn, we breakfasted alongside the yelping cries of yellow-naped parrots ransacking the tropical almond tree in the yard and dined in the evening with screeches of white-fronted parrots squabbling in the black mangrove on the channel.

The locals poach their chicks for commerce.

Should you care to look closer at this place, you may observe ghost crabs and frigate birds snatch clockwork toy olive ridley hatchlings from the hard black beach, just like in the late-night documentaries on the nature channels, or thin lines of blackskimmers in formal attire elegantly skive the surf with neatly lacquered beaks.

There are trophy class snook that glide silently past the bar around about when the high tide mark on mangrove prop roots back in the estuary is girdled by a restless sea. You can almost convince yourself that you really do see the silver dollar eyes of these phantoms from the end of the beach when the tidal stream runs gin clear at the height of the dry season. When it's not, their presence is betrayed by nervous schools of baby mullet that fling themselves into the sky in an attempt to evade capture. These savvy old hunters scorned what I tried to believe were expertly presented Deceivers on a nine-weight fly rod but would chase a stainless-steel spoon flung lazily off the end of a battered old bait caster with the rabid zeal of greyhounds after a crippled rabbit. On the frequent occasions that we did not manage to hoodwink them, when bought from local fishermen they tasted best grilled over not-quite-dry mesquite branches, basted with virgin olive oil, the juice from yellow limes, and brined green peppercorns.

The black crab gumbos tasted even better still.

Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) surveys tropical flood forest. Image: J. Vannini @2021.

I have watched ospreys dive after smaller snook, ladyfish, and seabass on many occasions here, but they never seemed to have any more success than my five-dollar tarpon flies and me. The visible failures by full-time professional fisherman did a lot to salve a wounded ego.

°

Later, should you choose to thread your way through the legs of those granddaddy mangroves that stockade the back of the beach–but give yourself a couple of hours if you chose to paddle instead of outboard it–the estuary opens up on a shallow lagoon covering about three hundred hectares. There are several picturesque small lakes down here, and I think that this particular one is the most scenic of them all. Admittedly, if you time your arrival to low tide in summer you will probably think this an odd judgement on my part, for this lagoon will be a small lake no more. Indeed, if you rented a motorized dugout back in town and time your arrival to low tide, you will probably be rather cross with me for telling you that there was a body of water here at all. Trust me. In a few hours, due to lunar magnetism, hydromechanics, and a lot of other things we like to pretend to understand, the lagoon comes home from the sea. In the meantime, jump out and help your boatman portage your dugout up towards the north end of the channel. While you mutter softly and sweat, then curse loudly and sweat, consider those three islands standing out in the middle of all that stinking mud and imagine them drop-clothed with about fifty thousand ibis, wood storks, snowy egrets and immature little blue herons. Too bad it's not July or August, because you would only see this scene in July or August. Set against a backdrop of rose quartz sky and the two tallest volcanoes on the Middle American Sierra Madre. That's when the water birds are here in a big way from the rookeries on Isla Puntachal, up the coast a ways on the south side of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Oaxaca. And only after six in the evening. True, the good birds do start arriving around five-thirty, but it only gets really "Woof!" after six.

If it were a clear August evening after six and I were with you, stinking of pure DEET, I might point out that there were but a handful of cattle egrets out in that squawking snowfield that had just fallen on the mangroves. In fact, you would notice so few that you might wonder why I mention them at all. I wouldn't except that the presence of these few crass, Old World commensals mars an otherwise perfect scene composed of tens of thousands of carefully executed white daubs representing our most elegant native waders. Not enough to ruin it mind you, just enough to rattle the sensibilities of a purist.

But I know that you now look at these small islets capped by young mangrove, reeds, and and swamp fern, seemingly barren of avian life, take a sip from your warm water bottle, think me quite the liar.

°

Close to our house above the estuary is a well-scorched clearing amidst a climax stand of red mangroves provoked by a smuggler's Beechcraft that missed the runway last year in a very definitive manner. This miscalculation caused local residents to climb from their beds at two in morning, pile into small craft, and see for themselves what had caused all the commotion. There wasn't much left of the plane or the pilot, but the body of the copilot and a representative sample of the cargo, somewhat singed and otherwise heat-volatized to be sure, were recovered from the channel after having been thrown free when the aircraft's fuselage shattered on impact. The army showed up a few hours later to retrieve what was left of the perico. They said there was still something like forty or fifty kilos of it. The soldiers left after a thorough reccy of the swamp to assure themselves that none was left behind that might wire the local shrimp population.

While almost certainly none was, and with the clarification that I would never impugn the honesty of my slightly sketchy but mostly friendly neighbors, there did appear to be a remarkable number of people wandering aimlessly down the beach until well past midnight for the next several weeks.

°

Bare-throated tiger heron (Tigrisoma mexicanum), Manchón-Guamuchal, Guatemala. ©Peter Rockstroh 2020.

Just past the northern end of the prettiest of lagoons down at this spot, the freshwater marsh creeps up on the white mangroves and buttonwoods and overwhelms them with an almost audible suddenness. Here you are in the sunlight again, under a wide sky of a tropical blue Pacific hue that seems to inspire cold climate writers to breathless superlatives, so we'll leave it at that for now. The first tiger herons flush–cwawk, cwawk, CWOK!–from just behind the cattails and spider lilies that fringe the channel. Sungrebes cannonball from the banks, red-winged blackbirds, and ruddy seedeaters swarm over the heads of limpkins and purple gallinules, while a juvenile snail kite teeters uncertainly on the breeze. As a family of chachalacas glides across the channel, you begin to notice the first handfuls of jacanas skittering from one side of the channel to the other while spoonbill couples stream by like errant Japanese kites.

Way, way out on the northern end of the marsh, a few kilometers past the last of the Sabal palm hammocks that dot the landscape, there are a series of shallow, red sand-bottomed puddles. These fill yearly with white pelicans down from reservoirs and ponds on the Great Plains, and dabbling ducks bred in seasonal western prairie potholes. The migrant pelicans arrive pretty much all at once, and late November or the first week of December is a good time to see them parachute in by the hundreds. At first glance, they will probably remind you of wood storks when they're soaring, but, after a few moments inspection with decent optics, you'll notice the head and neck aren't quite right. The mallards, scaup, ringnecks, shovelers, redheads, widgeon, and pintails just seem to materialize one clear December morning, and there they are, tipping and preening alongside the blue-winged teal that are the first arrivals in the early fall. Once we were even scoped out by an errant whistling swan down, no doubt, on a congressional fact-finding tour. During the first couple of weeks of their stay, these waterfowl are shy to a fault, and will flush well outside of shotgun range. I suspect that somewhere between being fêted by kindly retirees on water traps at country clubs in Colorado and Arizona and sneaking into this jungle marsh under cover of darkness, first year birds discover religion in the form of hordes of Mexican gunners that assemble every year on the marshes from Culiacán to Salina Cruz. So they arrive, wildly spooked, man and boat-shy, and rocket off the surface when you appear on the horizon. The benign climate and relative scarcity of brother sportsmen appears to work wonders on their frayed nerves, for a month later these same Gringo ducks will permit close approaches while they're feeding on what looks suspiciously like garden variety evil green slime.

Entonces, Danilo, our local boatman, and me are standing in water up to our thighs early one morning, watching a cloud of a couple thousand native black-bellied whistling ducks disperse over the marsh after an impressive first flush. There's a black-collared hawk and a gathering of yellow-headed turkey vultures rocking back and forth overhead. My young companion asks what black-collared hawks eat, and I give him a quick review of the different specializations of the region's raptors. In closing, I mention that there are some of them in the area that hunt other birds.

He looks somewhat skeptical, asks, "Does that include ducks as well?” and I respond, "Yeah, sometimes."

A small flock of blue-winged teal that had popped up out of a creek just in front of us was about to settle in the rushes further out.

Right on cue–and you can’t really make this up–a passage peregrine falcon so big and dark that she must have hatched out at a twenty-story aerie in the Canadian Maritimes rows determinedly over our heads obviously looking for a mid-morning snack. The bird has shoulders like an Olympic swimmer and a chest like...well, you know. What I know is that I have falconer buddies in the 'States who would sell their wives and daughters into slavery for a chance to point a bird like this at lesser prairie chickens or sharp-tailed grouse. All the Gringo ducks in sight head instantly for open water. Foxy Miss Peregrine seems unfazed at having lost the element of surprise–no big deal, right?–opens her sails over a weak thermal and rings up quickly to slum with the vultures way overhead. Several minutes later, when she seems to be heading for deep space, we begin to drag our skiff up a set of sleek rapids formed by the river running over a waist-high hard pan ridge. This is the highest point for kilometers around.

The blue-wings we had flushed earlier jump close in again in unison, bank, and head east at very high speed towards a broken line of willows in the distance.

From force of habit I glance up. Much to my surprise the falcon, a mote high on the skyfield moments earlier, is already arcing towards the flock at something like two hundred clicks an hour, now fully on the gas, her wings pumping hard all the way down while I briefly try and locate her with the glasses. The teal are only ten or fifteen meters over the marsh, so I know from past experience that they're going to veer and ditch before she intercepts and, ‘mano, you could kiss the book on that fact. There are four of them flying all bunched together, a slate-headed drake with half moon war paint on his face spinning a little off to one side, and they're about eighty meters out from us now, racing for safety.

Surprise.

I drop my binoculars just in time to see the falcon bust the momentarily isolated drake all the way up to puddle duck heaven. A nanosecond later, she's poised, proud and Valentine heart-shaped, presumably looking pretty pleased with things in general over her left shoulder from thirty or thirty five meters above the spot where she had ricocheted off his back. The handsome little drake is a limp rag, crumpled up and free falling, as dead as charity by the time he vanishes into the tall grass.

A friend’s trained, captive-bred juvenile peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) having a snack after a short flight in northern Wyoming. ©J. Vannini 2020

The kid seemed impressed. Hell, I'd seen all sorts of variations of it before hawking up north and I was impressed. The falcon's out of sight now, having alighted alongside her breakfast somewhere back there, and I'm thinking that great peregrines are surely the reincarnated, cavalier spirits of twenty year-old Mustang and Thunderbolt pilots whose lives ended with abrupt suddenness, but who refuse to fade away.

Anyway, there was something immensely satisfying in having witnessed this encounter between two very fast tourists who had come to duel on our wetland from separate points a few thousand kilometers from here. Danilo is thumping the side of the skiff in glee, shouting, “¡A la Gran Puta! ¡A la Gran Puta!”.

A la Gran Puta, indeed. I fish for a couple cans of locally smuggled Tecate in the cooler, iced just so, and we toast our sleek young visitor's coup.

And somewhere very near us, the ghost of old man tiger lifted his head from the ground at the ruckus, squinted back the blackflies in the shade of a Palo Blanco, yawned roll-tongued and long-canined, then continued his siesta.

°

Down the beach a way lived our token Peace Corps volunteer. Like many Peace Corps volunteers I've met over the years, he is pretty idealistic. Unlike most Peace Corps volunteers I've met he was also quite effective at getting his job done.

Our Peace Corps volunteer was involved in a mangrove reforestation initiative and was charged with managing the town's sea turtle and green iguana hatchery. My neighbors appeared to like him a lot. He's blonde, amiable, and surfed stylishly. The teenagers in town still idolize him. He taught a few of them to shred, then craftily bartered access to the half dozen boards that lined the front of his hut for their labor in community projects. Over time, he molded some impressionable young minds and attitudes around here. We missed him when he departed. Nevertheless, he left behind a hybrid surf and natural resources conservation club that call themselves, “Los Homeboys" that seems lazily interested in saving the estuary.

Like, they be pretty damned stoked, bro’.

°

There are several large boat-billed heron rookeries down at this site. Boat-billeds are shy, nocturnal creatures that prowl the warm backwaters from dusk to early morning in search of crayfish, frogs and baby turtles in Guatemala’s Pacific coastal marshes. I suppose that I'm obligated to mention here that their numbers are dwindling across the northern American tropics. Anyway, as is the case in most herons when they hatch, their kids look uglier than an arrest warrant served on Christmas Eve. But in contrast to most herons, a week later and they're impossibly Daffy Duck-with-a-mohawk cute. It pains me enough to see a few dozen nestlings flopping helplessly in the mud when the riparian scrub these colonies are located in gets felled and fired every year during the early dry season. From their hysterical reaction, I gather that the parents seem to detest this event even more than I do.

But it's corn planting time on high ground on the south coast and, after all, folks down there have to eat.

Boat-billed herons are not beautiful birds in the lovely cotinga, Wilson’s bird of paradise, nor violet touraco sort of sense. Nevertheless, I find them irresistible because they remind me of those very smartly-dressed, quietly aristocratic Tuscan girls whose noses might be considered a bit too prominent to those who favor petite, surgeon-altered models. But believe me fratello, some of those doe-eyed Italian regazzas are potential heartache material, prominent beaks notwithstanding.

°

Olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) entering the surf after laying eggs. ©Fred Muller 2020.

At dawn, if you take a walk down the glittering black beach, with whimbrels down from the high Arctic hop-scotching down the surfline and ethereal-looking guardian angel tropicbirds from the mid-Pacific coasting past on set wings and streamer tails, you should take the time to look for tracks of nesting sea turtles. Olive ridley and leatherbacks, mostly.

Hawksbills, every now and again.

You don't often see turtle tracks anymore because that's the way things are, but you should look for them anyway because that's the way things should be. If you're lucky, you'll have a few spotted dolphins that race parallel to the yellowfin tuna packs coursing baitfish just the other side of the crash and boom to keep you company, and they're certainly pleasant enough company.

Personally, I've given up looking for turtle tracks when I see human footprints on the beach, because I know what I'll find when they converge. This piece of shore used to be a big black turtle rookery at the beginning of the 20th century. Then the locals found a lucrative market in turtle eggs and calipee. Too many paths converged, so we don't see any black turtles at all these days.

The trick here, the real trick here, is to find old man tiger's prints, ostensibly a few years' gone from this particular beach. Not that you can see them, mind you. But I would swear I have felt them twice on solitary evening walks down the sand, splayed deep under my bare feet, phantom tracks recalling the passage of the last Guatemalan Pacific coast jaguars who ambled over from their mangrove sanctuary to hunt sea turtles in the moonlight.

Then, one day, just a few too many paths converged.

°

Camera-trapped northwestern Costa Rican Pacific coast mangrove jaguar feeding on an olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) kill. Image courtesy of and ©Luis Diego Torres.

Later in the morning, after boatloads of hapless Chinese immigrants looking for work have swarmed furtively in, and boatloads of hapless Highland Mayans looking for work have swarmed furtively out, you should stop near the tidal channel and examine the catch bottles of the people netting post-larval shrimp for the farms back behind you. The pulguilleros, as these salt-cured individuals are called on the Pacific coast of Central America, strain the surf with plankton nets for a few hours a day. If it’s a very good day, when the post-larvae are flocking into the estuary, they make enough to keep them from having to chop mangroves for sale as firewood to the trucks that wait as patiently as death in town.

If the surf is high and clean that day, the collecting jars will pulse with translucent baby shrimp, together with tiny eastern Pacific reef fish caught up in the benthic migration. Hold one close; take a deep breath so you don't fog the glass, and look. Sometimes you'll see half-inch canary yellow trumpetfish and platinum threadfins, or wasp-banded Moorish idols and Cortez's angelfish fry mixing with microdot ocellated boxfish so very blue that they would intimidate any self-respecting piece of lapis lazuli. You carefully place the jar back in the shade of a coco frond lean-to that shades the catch, then the pulguillero is back with another net full of p-l's. Emptying the contents into the bottle, he looks up, smiles broadly at you, and then turns to check on his inventory. Another plankton net is fixed over a plastic bucket, contents of collecting jars poured over the mesh, tiny fish plucked expertly from a madly hopping mass of p-l's, tiny fish gasping on the sand.

By tomorrow their gorgeous miniscule corpses will have withered to nothing and been blown down the beach to return to the sea, nothing to remember, nothing to mourn.

°

If you're like a good friend of mine, who prides his talent for nature photography, you might decide to walk down the beach late in the afternoon hoping to find a big log rolling on the tideline. Thinking, like my friend, that storm-tossed saltwater logs often harbor interesting life forms that are worth taking pictures of, you might spy one. And then be very surprised when the log turns and displays its toothy irritation at having been swept down the Río Naranjo and shunted through Waimea-like surf. Stepping back very quickly, I hope that you might be pleased that we still have very large American crocodiles washing up on this black sand beach.

Large adult American crocodile (Crocodilus acutus), Costa Rica. Image ©W. W. Lamar

Based on the available evidence, I suppose that big crocs are present in acceptable numbers at this spot. I came across wide belly drags out on the floating meadows every now and then, leading to inaccessible ponds back on the flooded grasslands. With some regularity, the field biologists who worked with me reported twin eyeshines that were too far apart to be caiman when they were out on the marsh at night on the way to blinds that they use for surveying waterfowl. Also early on in our work there, a croc measuring almost four meters effortlessly dispatched a would-be hunter who harassed it; another three meter long acutus wandered out of the swamp and into the town of Las Murenas. Both these animals, in addition to the one mentioned above, ended up as smelly, crudely tanned hides.

So that was how that year ended. Final score: Los Pescadores Locales, tres - Club Cocodrilo, uno.

°

With a ripple and a swirl that could be a big fish, but with a gestalt that you are familiar enough with to know that it is not, a young otter vanishes into a deep channel up on the marsh.

Anyone who has had the opportunity to make the acquaintance of an imprinted, housebroken otter knows that mankind missed a great opportunity to domesticate this animal back in the late nineteenth century when British sportsman-scrivener Osbert Salvin, Esq. was pushing the limits of human interaction with wild critters by training cormorants, booted eagles, cheetah, and otters for the chase. Sadly, the leisure pursuits of monied gentlemen have passed from vogue and instead, no doubt driven by our baser instincts, we chose to share our lives with that most vulgar of all mustelids, the ferret.

Having not been partial to ferrets since I observed a startled “tame” one latch on to the eyelid of a very surprised schoolmate in England, and being extremely partial to otters of all kinds, I think it is worth noting here that we appear to have made a terrible mistake.

The downside to house-trained otters is that they are curious and hyperactive enough to–after a few days close association–drive even the most serene person to pound on the gates of the nearest mental hospital, begging opiates and admission. Trust me on this. I’ve been on close terms with more than a few very affectionate pet otters in both my own and friends’ homes. These minor flaws are, however, offset by engaging personalities, songbird voices and a truly remarkable degree of intelligence and “altruism” for a small carnivore.

I still don't understand our failure to see the added value that otters bring to our existence. Instead of elevating them to the cult status of Pooh and Bambi, we have opted to harass a number of species to the brink of extinction. And all this while the lowly ferret has managed, well, to ferret its way into the hearts and homes of snarling adolescents with far too many tattoos, "Fuck you" haircuts, and rings in their noses.

The otters down here are southern river otters, and pelt hunters have persecuted them to a point where they have been listed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species/CITES. Appendix I of CITES is where we remit all of the flora and fauna whose parts and wholes we are currently in the process of loving to death. For any plant or animal unlucky enough to have been provided with a ticket, Appendix I of CITES is the last station on a one-way trip to the boneyard.

All aboard?

°

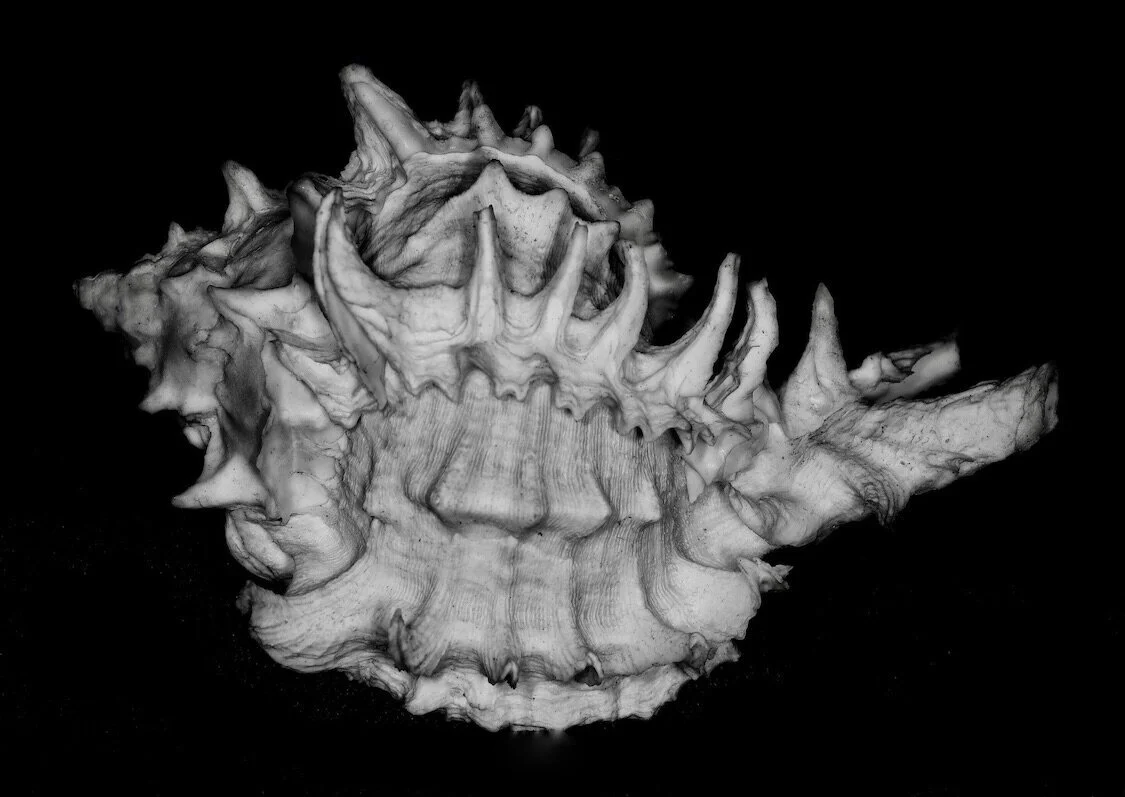

Pink-mouthed murex (Hexaplex eurythrostomus), fairly shallow coastal waters from Baja California Sur to Perú. ©Ron Parsons 2020.

And, well, that was the Manchón-Guamuchal in southwestern Guatemala when I finally thought I knew it well enough to try to put it down on paper. There were a few things I that would have liked to see that I never got to see before they vanished. I wandered onto the scene far late to see the last Rodinesque silhouettes of jabiru storks brooding on eel shortages out on the marsh (circa 1930); a few decades too late to see the last Baird's tapirs nibbling on heliconias in river forest (circa 1960); just a wee bit too late to see an area rancher shoot the last jaguar and her yearling cubs on a backwater hammock (circa 1990).

For a while I thought that we could save it, perhaps a rather conceited and ingenuous view, considering present circumstances in the American tropics. I once believed that there were a lot more people in this country that understood the need for places like this to regain one's perspective and to retain one's sanity. Since its obituary has yet to be written, some friends are still down there, "working with the community".

Sure.

Nevertheless, like almost all of the last relics of wilderness left in Central America, the die appears to have been cast by the local populace.

After all, folks down there have to eat.

Now I sit and muse on how things down at El Manchón must change for the worse much too soon for all of us. I am very pleased to have had the incredible good fortune to see it like this still, and saddened at knowing that it will be vandalized beyond recognition within my lifetime.

And somewhere far distant from where I now sit, the ghost of old man tiger seeks a place where men and big cats can somehow get through this awkward relationship that we began way back in the Late Pleistocene.

°

Then one day it's a perfect sunlit afternoon in late March and a half-kilometer square of blue-winged teal lift simultaneously from an exposed tidal flat. They are instantly and cleanly aloft, tens of thousands of wings precision-clipping the sky, wheeling once undecided before racing north.

Seeing them head home, my heart breaks for a moment, and then I too want so much to be far away from this insane country, from this cradle of vampires, from this maldita pesadilla. I try and shake the feeling. Turning towards the strand, I fire up a pretty good box-pressed Padrón, stare up at the palm crowns through broken skeins of cigar smoke and listen to the royal terns cry for the Manchón and all the other battered wild places in Central America.

It is nothing, really. But you had best leave before the black flies start biting.

And me? I suppose I'll stay a while longer, try to forget about the rest of a very screwed up world just for today. Maybe snag a pocket flask of 18 year-old liquid feelgood from the field station and wander this glittering black beach for a few hours, one last time.

In the end I suppose all I can hope for is that, rather like those of that last Guatemalan mangrove jaguar, someday my footprints will remember I was here.

°

Hatchling olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea), almost home, Guatemalan Pacific coast. ©Fred Muller 2020.

°

Afterword: Like almost everything of mine (JV) on this site, I wrote this piece as an exercise, more or less in present form (albeit with a lot more bad language), as “colored” field observations 27 years ago. In the interval between my fieldwork doing floral and faunal inventories while drafting a protected area feasibility study for Guatemala’s conservation authorities (CONAP) at the Manchón-Guamuchal with the Fundación Interamericana de Investigación Tropical (FIIT), mostly under grants from World Wildlife Fund-U.S. and the U.S. National Fish & Wildlife Foundation, and now, things have gone rapidly downhill for this Ramsar-designated wetland of international importance. A huge upsurge in narcotics and human trafficking from the already alarming levels referred to above, mangrove deforestation, land grabs, beach erosion, unregulated expansion of shrimp farms, subsistence hunting, plummeting regional and long-distance migrant bird numbers, horrific volumes of plastics in the ocean, ad nauseum have conspired to wreck yet another of the world’s amazing, unique, and fragile natural treasures. There are a couple Guatemalan conservation NGOs still working in and around the Manchón, but–seriously–good luck with that. Just as it did in the early and mid-20th century with the export-oriented trade in turtle calipee, heron and egret plumes, and crocodile, otter, and spotted cat hides as well as live parrots and macaws, the insatiable current demand for cocaine, synthetic opioids, palm oil, cheap shrimp, and even cheaper labor by clueless and selfish consumers in northern economies further fuels environmental destruction throughout tropical America in once-magical places like the Manchón.

Now, I can never really go back again because, as we all know, humans always “win”.

°

In memory of my friend, fellow naturalist, and godson Patrick.

©Exotica Esoterica LLC 2020-2025®, ©Jay Vannini 2020, ©Peter Rockstroh, ©Fred Muller, ©W. W. Lamar, ©Ron Parsons, and ©Luis D. Torres.

Follow us on: