Fer-de-lance

“Nemo me impune lacessit ”

by Jay Vannini

Hell’s Hole Punch. The sharp end of a live Guatemalan barba amarilla (Bothrops asper) shown in situ in lowland tropical rainforest. This large, irascible, and highly toxic pit viper species is responsible for the majority of snakebite fatalities in the Western Hemisphere. Image: ©F. Muller 2020.

King cobra, black mamba, taipan, habu, diamondback, bushmaster, fer-de-lance…

…are all venomous snake names that bring gleams to eyes in the marketing departments of armament and tactical gear manufacturers, not to mention those of “extreme” nature documentary filmmakers. For the rest of us, they evoke images of the defensive postures of some of tropical wilderness’ most lethal residents as they rear up to confront threats.

I’ll start this off by saying that, despite contemporary interest associated with this storied name, it seems nowadays no-one other than some ecotour guides, online journalists, and hidebound Gringo reptile collectors call Central American viperid snakes “fer-de-lance”. This is a Creole-French term coined by naturalist Bernard-Germaine de Lacépède following a visit to the southeastern Caribbean in the late 18th century and means spear- or lancehead, an allusion to these snakes’ crown shape when viewed from above. While it is still mentioned in the herpetological literature in association with Martinican and St. Lucian lanceheads (Bothrops lanceolatus and B. caribbaeus), it is not used on the islands where these snakes occur and apparently never has been (Campbell and Lamar, 1989; 2004; W. Lamar, pers. comm.)! Some make the case that this is a good optional common name for the very widespread South American lancehead (B. atrox) but, other than in Guyane/French Guiana, I disagree. Why fer-de-lance would be an appropriate name for two snake species whose ranges are otherwise restricted to countries where indigenous languages, Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese, and English are spoken–but not French–is a bit of a mystery to me.

But it certainly caught your attention, didn’t it?

Head detail of a large adult St. Lucian lancehead or fer-de-lance (Bothrops caribbaeus) in the author’s collection in Guatemala during the late 1980s. Based on admittedly limited experience with a trio of these rather nondescript insular pitvipers, I came away with the impression that they were consistently more “touchy” than most B. asper that I’ve worked with. Author’s image from 35 mm slide.

Ainsi, les fer-de-lance ensuite!

In 1934, American crime fiction writer Rex Stout published the classic Nero Wolfe murder mystery “Fer-de-Lance” in an obvious nod to both an earlier tale of his own, “The Last Drive” (1916), and Arthur Conan Doyle’s famous Sherlock Holmes short story, “The Adventure of the Speckled Band” (1892). Both works of suspense employ improbably compliant exotic venomous snakes and elaborate mechanical devices to assist the murderers in dispatching their victims.

Detective fiction author, screenwriter, and literary legend Raymond Chandler, of “The Big Sleep” (1939) and “The Long Goodbye” (1953) fame, who was also a discerning and respected critic of crime stories, shook his head and chuckled at these types of farcically complex murder plots, evoking, “…hand-wrought dueling pistols, curare and tropical fish…” in “The Simple Art of Murder” (1950).

In one devastating passage, Chandler managed to run a double-decker bus over not only Conan Doyle and Stout, but also the popular 20th century suspense writers Agatha Christie and Sax Rohmer.

Thus ended the hopes of future starring roles for tropical vipers in highbrow crime fiction.

Among the larger and more notorious venomous, (or “hot”) snake species around the world that inspire anxiety in people who coexist with them in nature, the reality is that most are fairly rare, retiring, and non-confrontational animals when encountered in the field. Nonetheless, accidental or intentional close contact with any of them can be a hair-raising and life-threatening experience when an alarmed, highly venomous snake opts for “fight” rather than “flight”.

The species I will discuss here is Bothrops asper (Garman, 1883), a very formidable animal in every way, whose Latin binomial’s free translation is “the pit-faced rough one”. This snake’s scientific name has traveled a rather meandering taxonomic path since its first description in 1868 and is once again the subject of debate, which I will now sidestep and forget about for the rest of this article.

In actuality, the names used by rural people for this species are myriad across the northern American tropics and a small sample include: nauyaca/nauyaca real (México), cantíl cola de hueso or nauyaca cola de hueso (Guatemala and México), tamagás (Guatemala), devanador (Guatemala), barba amarilla (Guatemala, Belize, Honduras and western Nicaragua), Ik’bolay (Guatemala), tommygoff/yellowjaw tommygoff (Belize), terciopelo and toboba (Costa Rica, southeastern Nicaragua, and western Panamá), equis (Panamá), boquidorá (Caribbean Colombia), mapaná/mapanare (Colombia), and Central American lancehead (U.S.). Many American and British herpetologists, reptile collectors, and regional ecotourists seem to have adopted the rather sexy Costa Rican designation “terciopelo” for common name usage in English, which is also fine by me.

A portrait of a Costa Rican eyelash palm-pitviper (Bothriechis nigroadspersus, but formerly known as B. schlegelii) in nature. The deep loreal pit housing infrared receptors is clearly shown here between the small nostril and large eye and gives crotaline snakes their common name “pitviper”. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2022.

The southern U.S., México, Central, and South America house a remarkable diversity of often beautifully colored viperid snakes of the subfamily Crotalinae, commonly called “pitvipers”. All are moderately to dangerously venomous terrestrial and arboreal snakes easily identified by the conspicuous thermoreceptive pits located between their nostrils and cats’ eyes, not to mention their big front teeth.

New World pitvipers that combine very large adult sizes, potent venoms produced in sizable quantities and sometimes truculent or otherwise unpredictable personalities are fortunately few. Nonetheless, unexpected up close and personal run-ins in nature with large diamondback rattlesnakes (Crotalus adamanteus and C. atrox), Mojave rattlesnakes (C. scutulatus), Mexican West coast rattlesnakes (C. basiliscus), Neotropical cascabel rattlesnakes (C. simus, C. tzabcan, and C. durissus), the different bushmaster species (Lachesis muta, L. stenophrys, L. melanocephala, and L. acrochorda), as well as any sizeable examples of all Neotropical lanceheads (Bothrops and Bothriopsis species) may certainly prove fatal or limb-threatening.

A young adult captive-hatched Central American bushmaster (Lachesis stenophrys) flattening its neck and giving me the evil eye to indicate that it had quite enough of this particular photography session. Shown in my personal collection in Guatemala, late 1980s. Despite their apparent docility at times, captive-raised bushmasters often have very strong opinions on handling that are ignored at one’s peril. Called matabuey (ox-killer) in Costa Rica, and la verrugosa (the warty one) in Panamá, this is among the New World’s largest venomous snake species. Contemporary record lengths are around 8’ (2.45 m), but they probably attained much larger sizes prior to the widespread persecution they’ve suffered over the past ~150 years (W. Lamar, pers. comm.). Its South American close relative (L. muta) can still reach almost 12’/3.70 m in length in exceptional cases. All four bushmaster species, especially L. melanocephala and L. muta, are bold, intelligent, and formidable snakes in nature and in captivity. Their frequent fearlessness, very large mature size, exceptionally long fangs, and potent venom make them dangerous snakes to wrestle with when they’ve had a bad day. The genus’ Latin name was inspired by Lachesis, the Fate who measures the thread of human life, daughter of Darkness (Erebus) and Night (Nyx). ©Author’s image scanned from 35 mm slide.

In a 1994 article published in Biotropica on Bothrops asper bites in field researchers working in Mesoamerica, Arizona physician and New World venomous snake expert David Hardy called this snake, the “ultimate pit viper”. It is certainly an apt description and over the past 25+ years the phrase has become sure-fire clickbait. The few remaining Lacandón Maya forest communities in eastern Chiapas, México call this species Hach Kan, the “true snake”, just as they refer to themselves as Hach Winik, the “true people” (Nations, 2006). It seems the lowland Maya figured out the whole “ultimate pit viper” thing a few thousand years before we did.

Really? The “ultimate pitviper”? The “true snake”?

For millions of rural people in Mesoamerica, Bothrops asper is, indeed, the only snake worth talking about.

Above, images of two superb Mayan polychrome ceramics dating from the latter part of the Late Classic Period with creation scenes depicting the lightning god K’awiil (God K), shown standing on the left in both pieces, with its characteristic snake right leg enveloping the reclining and partially nude women in its coils. This lengthy appendage ends with what is believed to be an ancestor figure or deity emerging from the elaborate foot of the lightning God in both cases - although not entirely evident in the cropped rollout image on the right. The skin pattern on the god’s long, slender, serpentine legs are perfect matches for Bothrops asper, which is a common large snake in the Mayan lowlands. Compare image details above with dorsal markings on the live snake shown below. Image left: ©Jay Vannini 2024. Image on the right in the public domain.

The three names that I have heard most commonly employed in different parts of the region are nauyaca (= four noses in Nahuatl, pronounced “NOW-oo-yah-kah”, southern México), barba amarilla (= yellow beard in Spanish, pronounced “BAR-bah AHM-ah-REE-yah”, northern Central America), and terciopelo (= velvet in Spanish, pronounced “TARE-see-oh-pello, southern Central America and Panamá). From decades of use in-country, I favor the Guatemalan and Honduran name barba amarilla and will use either this, the commonly used nickname barba, or its Latin binomial Bothrops asper throughout the rest of this article.

Adult barba amarilla (Bothrops asper) in nature in eastern Guatemalan lowland tropical forest. This animal clearly illustrates the origins of the Central American Spanish names “yellow beard” and “velvet”. Image ©F. Muller 2020.

After my wife heard a native Arabic-speaking friend who very occasionally but always comically mangled local Spanish terms refer to them as, “Tus malditas Barbaras amarillas” (“Your damned yellow Barbaras”) in Guatemala in the early 1980s, they’ve been “Las Barbaras” (The Barbaras) around my house ever since.

Why these snakes are called lanceheads. A map of the cosmos printed on the crown of a central Peruvian speckled forest-pitviper (Bothrops [Bothriopsis] taeniata). Image: ©F. Muller 2020.

Despite being unrelated and quite different in their respective ecologies, in terms of medical importance and ability to sustain viable populations near human habitation in rural areas despite constant persecution, barba amarilla appears to have parallels throughout much of Africa with puff adders (Bitis arietans) and in tropical Asia with Russell’s vipers (Daboia russelii; Conan Doyle’s infamous “Speckled Band” mentioned above). At maturity all are large, heavy bodied viperids with long fangs, sizeable venom glands, highly toxic venoms, large litter sizes and–often it seems–hair triggers when closely approached by humans or livestock.

Envenomation by Near Eastern, Asian, and American pitvipers can be extremely serious and life-changing events even if the snake is one of the smaller species or a juvenile. I have had healthy adult male friends hospitalized for days following bites by captive neonate Neotropical pitvipers. While a surprisingly high percentage of pitviper bites appear to be “dry” (i.e., little or no detectable venom is injected during the bite), a small but significant percentage can involve unnerving instances where the snake may even sink its teeth into its victims’ extremities, hang on bulldog tight, and deliberately pump large amounts of venom into the musculature of its antagonist. This type of bite always has serious, and sometimes permanent, consequences for the victims. Given the complexity of venom chemistry across populations of even the same pitviper species that sometimes include neurotoxins, snakes’ lethality can vary enormously from one region to the next. This is (in)famously the case in Mojave rattlesnakes (Crotalus s. scutulatus) in the southwestern U.S. and northern México and cascabels (C. durissus, most subspecies) in South America. Venom from specific populations of C. scutulatus (so-called “venom A secretors”), have been shown to be >10X more toxic than snakes that lack this enzyme subunit.

You definitely don’t really want to find out whether the pitviper that might bite you has an obscure active neurotoxic component to its venom or not.

“A severe Bothrops asper envenomation can produce horrific effects on those unfortunate enough to get chomped, and falls firmly into the, “No thanks, none for me today!” category.”

So what happens when it catches the truck? Image: ©F. Muller 2020.

Venomous snakebite is considered a rare accident even in the wet tropical lowlands, but it is not altogether that rare in some regions of the world. A fairly recent study based on careful analysis of public health records across the American tropics suggests ~60,000 bites annually, with approximately 370 victims dying every year from bites (Chippaux, 2017). Data is known to be both incomplete and usually very retrospective. It is widely accepted that significant undercounting occurs since a high number of cases, particularly in remote areas, never reach treatment centers (Gutiérrez, 2014). In 2017 it was recategorized as a neglected tropical disease by the World Health Organization (WHO) following its removal in 2013 after only four years (Tumang Frare et al., 2017). For what it’s worth, the WHO’s current estimates for snakebite fatalities in the Neotropics are much, much higher than those documented in the recent Chippaux survey (Chippaux, 2017; WHO, 2019). Morbidity and mortalities have no doubt been greatly reduced since the advent of antivenin in the early 20th century and its improved efficacy dating from recent decades. The vast majority of both envenomations and fatalities in the Neotropics involve Bothrops species and among these the lion’s share are attributed to our star actor, B. asper, and its slightly smaller but equally short-tempered sibling species, B. atrox.

A villainous-looking female Venezuelan lancehead or Tigra Mariposa, Bothrops venezuelensis, shown in nature. This is a medium-sized but nonetheless highly toxic pitviper species. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2022.

A severe Bothrops asper envenomation can produce horrific effects on those unfortunate enough to get chomped, and falls firmly into the, “No thanks, none for me today!” category. I’ll forego the usual X-rated clinical shots of bitten extremities, but curious or morbid readers can easily find cringe-inducing examples online. Suffice to say that common early effects include sustained and stabbing pain, major edema caused by an impeded lymph flow, bleeding from gums, upper respiratory tract tissue, tear ducts, ears and other orifices, partial blindness, rapid fleshy tissue discoloration, and resultant necrosis. Later effects of even moderate envenomations include dermal tissue sloughing and blistering around the bite marks in a high percentage of cases. All this as well as troublesome secondary infections associated with these exposed lesions. Anything other than an obviously dry or very mild bite requires prompt antivenin and other support therapy to neutralize the venom’s effects and save a victim’s limb or life.

Despite outsized media attention paid to the infinitesimal number of snake-related accidents U.S. and European tourists suffer in Costa Rica, it is actually Panamá that has the highest per capita incidence of snakebite both in the region (~1,800-2,800 reported annually depending on the author/s) and in Latin America as a whole (Gutiérrez, 2014; Pecchio et al., 2018). Notwithstanding this relatively high number of envenomations for the country’s size, fatalities are surprisingly low (~20-30 a year) and a tribute to antivenin therapy. Panamanian snakebite numbers are very likely linked to the low elevations that prevail throughout much of the country, together with lightly to moderately disturbed habitats and high rainfall that favors high population densities of Bothrops asper. This snake is responsible for approximately 45% of all documented bites and almost all of the fatalities there (Pecchio et al., 2018).

A threat display by a mature yellow-blotched palm-pitviper (Bothriechis aurifer) in central Guatemalan cloud forest. Note the flattened neck, distended scales on the anterior part of the body, “S”-shaped defensive loop and (most importantly!) open mouth. A pitviper with the trigger fully cocked like this is likely to strike at any stimulus, however small. Image: ©F. Muller 2020.

Defensive responses by many large New World pitviper species include inflating the body to appear even larger (see images throughout this article of different Mesoamerican and South American pitvipers with distended upper body scales showing that they’re puffed up and pissed off), flattening the neck to draw attention to the head, open mouth gaping, “grimacing” by repeatedly flexing muscles on the head, leaving the tongue hanging out and static or in very slow movement (especially in mature rattlesnakes), elevating the anterior portion of the body well off the surface in a loose “S” shape in order to strike higher and faster that is sometimes combined with tail drumming or rattling to further indicate extreme alarm or displeasure.

Care to dance? Early stage threat stance of an alarmed Middle American rattlesnake (Crotalus simus) in Tropical Dry Forest of central Guatemala. This species, together with its close relatives C. tzabcan and C. durissus can exhibit the most extreme defensive displays of any rattlesnake species when fully on the loud pedal. I have observed very large examples elevate such that only a three-quarter coil remains on the ground and the head and anterior portion of the body are raised almost straight up to ~30”/75 cm off the ground. As is also the case in other large Crotalus species, particularly irate C. simus may leave their tongues supended in the air for minutes at a time, often laying it forked and flat on their heads to get a constant data feed from the immediate environs. Despite some reports that they are reluctant to buzz, I have found that mature examples of this species rattle on a consistent basis when closely approached. Image: ©F. Muller 2020.

Fully agitated, large adult barba amarilla confronted at close quarters have been called, “…a redoubtable adversary and must be regarded as extremely dangerous” by two recognized authorities on regional venomous reptiles, Jonathan Campbell and William Lamar (1989).

I heartily agree.

A large adult eastern Guatemalan rainforest barba amarilla (Bothrops asper) after dark - vigilant, poised, and ready for a knife fight. Image: ©F. Muller 2020.

While some mature individuals found prowling about at night on the forest floor or streamside can be shadowed cautiously at a distance with a headlight fully on them for several minutes before they decide to disappear under a log, glide down a hole, swim away or–in a trick guaranteed to get your attention–simply vanish into darkness, others instantly fall back into a fighting coil, raise their heads, and rapidly beat their tails on the ground in warning. A thoroughly annoyed barba amarilla will not hesitate to make long, lightning fast, multiple strikes towards anyone who chooses to press forward in unambiguous, “GO AWAY!!” messaging. I have never had one turn fully offensive and start moving towards me in an overt manner, but they will certainly fire both barrels at you even while semi-extended and in rapid movement if you’re along or astride their escape route. This sometimes erratic “slide-stop-strike” flight behavior is likely the source of widespread reports in rural northern Latin America that these snakes will not hesitate to attack when closely approached. Their speed over very short distances and unnerving habit of abruptly switching direction requires extreme care when within a few feet/meters of one that’s so angered or fearful it’s bumping against the rev limiter in terms of a defensive response. A recent, well-documented regional study showed that foot and lower leg bites represent ~75% of all cases (Laínez-Mejía et al., 2017) so calf high rubber boots are certainly very useful for protection. Light hiking boots are not. Bites on hands and forearms are also a real risk. I shudder when I think of the horrendous effects and almost certain fatal consequences that getting bitten on the face or neck by a big one would result in; both a close friend and an acquaintance have miraculously escaped this type of accident while in the field in Costa Rica.

¡Jueputa, maestro! A very irate adult Yucatán Peninsula Bothrops asper gaping angrily after failing to deliver a knockout blow to the photographer during a round of defensive strikes. This photo clearly indicates that it was game for Round Two. Barba amarilla from this region sometimes display unusual color patterns that resemble those of a few South American Bothrops species. Image: ©F. Muller 2020.

Under exceptional circumstances and when particularly infuriated, several large Bothrops species are now known to gape and eject venom for short distances at antagonists. This apparently rare, disconcerting/alarming and poorly documented behavior has been observed in wild B. asper in Costa Rica and B. atrox in Perú (W. Lamar, pers. comm. and filmed for a documentary) as well as in a captive adult Brazilian yarará (B. neuwiedi) in Guatemala by me. These events, together with an avalanche of well-documented reports of “dry “bites by large Bothrops, evidence the very precise muscular control these animals have over their venom glands.

Aberrant pattern subadult male Bothrops asper shown in nature, Limón Province, Costa Rica. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2020.

Neotropical venomous snake researcher Bill Lamar, in what I find a particularly good insight, has called this species “inscrutable” in that it seems as if they themselves don’t really know how they are going to react until they actually flip the switch. As evidence he recently wrote me that, ”…I have had them lie motionless, even when stepped upon; I've had them coil into a defensive ball; one shot between my legs as it fled; I've had one run up me better than halfway before abruptly turning around; and one that I will never forget…”

You get the point.

Unpredictable.

Barba amarilla alarm responses to potential human threats are the byproduct of a defensive arsenal refined over millions, not thousands, of years. It is highly likely that the impressive counter threat behaviors that many larger New World pitvipers employ have evolved entirely to impress and deter mammalian predators such as the tropical forest peccary species (Pecari tajacu and Tayassu pecari) and large opossums (Didelphis marsupialis), all of which are known to show resistance to crotaline venoms and occasionally feed on Bothrops, Crotalus and Lachesis species (Almeida-Santos et al., 2000; Sasa, Wasko and Lamar, 2009; W. Lamar, pers. comm.).

“Are they evolving to someday be able to swallow naughty children who stay up past their bedtimes? Who knows?”

Detail of dorsal pattern on an extremely dark colored adult specimen of Bothrops asper from Atlántida Department, northwestern Honduras. Note the bold white X markings on the back that are the source of one common name further south, “equis”. This one is from early 20th century snakeman Douglas March’s old haunts - see text below. Image: ©F. Muller 2020.

This species occurs along the Gulf coast of México from the El Cielo Biosphere Reserve in southwestern Tamaulipas state (located ~200 miles/320 km south of McAllen, Texas) throughout the southeast to the Caribbean coastal areas of the southern Yucatán Peninsula, Belize, the Pacific slope of the Sierra Madre of Chiapas, México and the volcanic piedmont of western and central Guatemala, throughout the Caribbean and Gulf slopes of Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua, both slopes in Costa Rica, Panamá, and Caribbean Venezuela, both slopes in Colombia as well as the upper Amazon basin, the Pacific slopes of Ecuador and into northern Perú. While irregularly distributed from sea level to middle elevation cloud forests throughout much of its range, it is usually much more common in lowland tropical rainforest or disturbed lowland habitats than at higher elevational levels (Campbell and Lamar, 1989; pers. obs.).

Barba amarilla are extremely variable in terms of pattern and color, both ontogenetically as well as across populations. Generally speaking, the ecotypes in southeastern México and northern Guatemala tend to towards gray, buff to reddish brown colors with chalk, cream or clear white cross marks on their backs, while Costa Rican and western Panamanian Bothrops asper can have very bold chocolate brown, dark gray or black ground colors with pure white, yellow or pale pink cross marking. Northern South American examples of this species may bear little resemblance to most of their Mesoamerican cousins (Campbell and Lamar, 1989; 2004).

Besides the considerable dorsal color and design changes evident across its range, at some localities barbas that have disproportionately large heads in relation to their body mass represent a small but conspicuous percentage of those encountered in the field (see image below and M. Fogden’s photograph of another in Savage, 2002). At one time I believed this might just another uncommonly expressed manifestation of sexual dimorphism in this species, but I have since realized that it does not appear to be correlated to the gender of the snake and is just an unusual individual trait. Presumably these “big-headed” snakes are able to feed on larger prey items due to their ability to distend their jaws wider than the average example they coexist with. What’s going on with this peculiar morphological variant? Are they evolving to someday be able to swallow naughty children who stay up past their bedtimes?

Who knows?

Large adult black and gold color variant of Bothrops asper from the Caribbean lowlands of Costa Rica. Note the very bright colors of Caribbean versant B. asper from Costa Rica compared to the Guatemalan animals shown here. Image scanned from a 35 mm slide: ©W. W. Lamar 2020.

It has long been suspected that isolated populations of Bothrops asper occurring on the Pacific slopes of Chiapas, México south to central Guatemala, as well as southeastern Costa Rica and western Panamá might warrant elevation to subspecies or even full species status Aragón and Gubensek, 1981; Saldarriaga-Córdoba et al., 2017; pers. obs.). In particular, the northern Mesoamerican populations along the Pacific coast and piedmont are completely isolated from their Caribbean slope cousins by the Volcanic Cordillera and presumably have been for more than a million years.

Phenotypic variation among Bothrops asper populations across its range was evaluated via DNA sequencing and discussed in Saldarriaga-Córdoba et al. (2017). In the concluding remarks, this paper includes mention of the earlier Aragón and Gubensek study comparing venoms from Caribbean and Pacific versant populations in Costa Rica that concluded a thorough taxonomic revision of Bothrops asper was warranted. For a variety of reasons other than sheer bloody-mindedness, I favor the theory that B. asper as currently defined includes several closely related, similar looking, but still undescribed species that will probably be resolved as such fairly soon.

A mature Caribbean coastal barba amarilla (Bothrops asper) in Guatemala with a particularly large head. The distended venom glands located behind the eyes are worth noting. Image: © F. Muller 2020.

In the forested tropical lowlands of eastern Guatemala, like other areas on the Caribbean coast of Central America and Colombia, barba amarilla are likely to be the most conspicuous snake seen by nightwalkers and can be especially abundant in some very productive secondary forest localities. In a 1920’s study conducted just east of Guatemala’s Izabal Department in the vicinity of Lancetilla, in Honduras’ Atlántida Department, one out of every 10 snakes brought into the old Serpentarium and venom extraction lab for identification were Bothrops asper.

These snakes are commonly found near permanent water such as rivers, streams, and swamps, as well as the aguadas that dot the lower Yucatán Peninsula. In my experience in Guatemala and from comments made by Costa Rican and Panamanian friends, the highest population densities in Central America occur in or adjacent to the interface of mature primary forest and pastures or recently planted tree crops. They can be particularly abundant in old growth African oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) plantations in Central America (C. Moya, pers. comm.; A. Solorzano, pers. comm.; pers. obs.). They may also be commonly encountered in the vicinity of rural refuse tips in the lowlands due to the presence of increased rodent populations. Juveniles and smaller adults may be arboreal, and fatal bites have been reported from young snakes encountered in trees.

Home ranges for both sexes in lightly disturbed lowland rainforest in northern Costa Rica range from 9.25 acres/3.7 ha. to 15 acres/~6 ha. Daily movements typically are less than 35’/10 m from daytime refuge to ambush site followed by less frequent longer distance movements when prey is depleted in any given area (Sasa, Wasko & Lamar, 2009).

Images: ©F. Muller 2020.

Juvenile barba amarilla are sexually dichromatic with males having white or pale-yellow tails (shown above left in a richly-colored eastern Panamanian snake), while females have pale-pink or pinkish brown tails (shown above right in a northwestern Guatemalan example). The conspicuous pale tail color in young males is the origin of the “cola de hueso” (bone tail) and “rabo amarillo” (yellow tail) suffixed names across its range (e.g., toboba rabo amarillo in some parts of Costa Rica). I have observed young examples of both sexes employ them in caudal luring to attract small lizards introduced to their enclosures as food items, as was also the case for many other young Neotropical pitviper species I have kept. When small they feed largely on a variety of arthropods, small lizards and frogs, then shift to small and mid-sized rodents as they mature. Sizeable adult females are capable of dispatching and consuming mammals as large as medium-sized opposums (Didelphis, Caluromys, and Philander species), young agouti (Dasyprocta species), probably juvenile coatis (Nasua species) and hog-nosed skunks (Conepatus species). Although I have not seen evidence of bird remains in fresh feces of large wild collected Bothrops asper held in captivity, they do feed opportunistically on any suitably sized birds such as ground thrushes (Turdidae) and tinamou (Tinamidae) together with others they may encounter (Sasa, Waska and Lamar, 2009). The hunt for arboreal frogs and small, sleeping perched birds may explain the presence of young adults in trees (Vega-Coto et al., 2015). Mature examples can shift back to feeding on large frogs in the absence of suitably sized mammalian prey (Wasko & Sasa, 2009; Sasa, Wasko and Lamar, 2009).

Ten newborn “Barbaras” (Bothrops asper), delivered days earlier by a wild-caught gravid snake from the Caribbean lowlands and shown in my Guatemalan collection in the late 1980s. Note pale tail tips on the neonate males visible here. Despite their small size at birth (~10”/25 cm), baby B. asper are quite capable of inflicting very serious or even fatal bites on adult humans. Author’s image scanned from 35 mm slide.

This species is, conversely, consumed by a wide variety of terrestrial spider and vertebrate predators when young, including large anurans as well as other snakes (both in cannibalistic events and by the larger Clelia species) and when mature by some bird of prey species, crocodylians, and peccary (Sasa, Wasko and Lamar, 2009; pers. obs.).

Barbas are sexually dimorphic when mature and individuals at or over 5’/1.55 m with any girth are almost invariably females. They are live bearing snakes (technically ovoviparous), that can produce very large litters in healthy mature females. I have had drops of just under 50 babies from large, gravid, wild collected snakes that gave birth in my collection in Guatemala, but there are documented reports of litters of over 70 in Honduras (March, 1928; Ditmars, 1931) and rumors of even higher numbers elsewhere. Neonates range from 7-11”/18-23 cm at birth and, as is shown here, easily sexed at this stage.

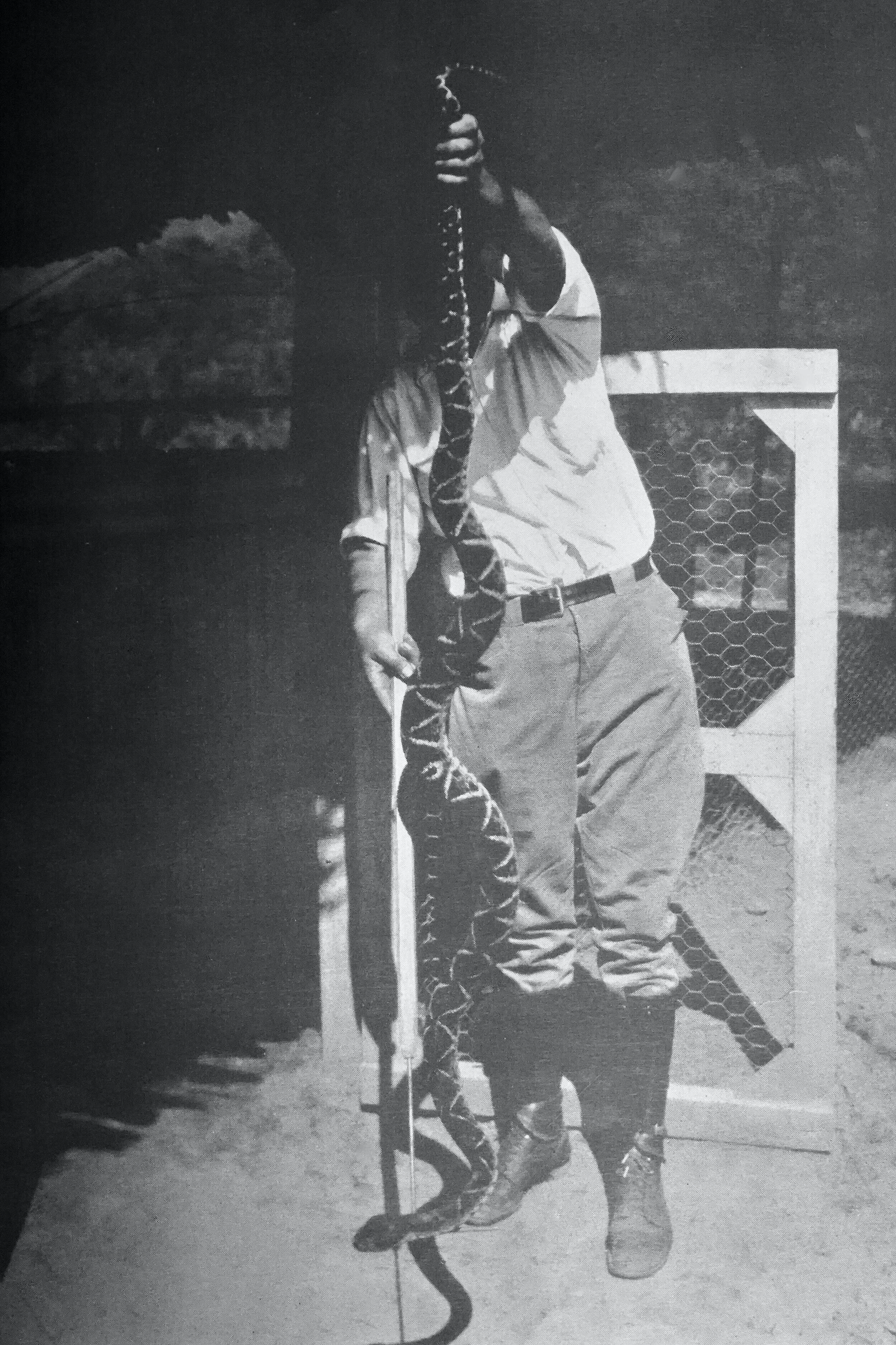

Douglas March (?) displaying a large adult female barba amarilla (Bothrops asper) at the Antivenin Institute of America’s Serpentarium in Lancetilla (Tela), Atlántida Department, Honduras in 1927 or early 1928. This animal was reportedly 8’/2.45 m in length but a cursory analysis of both the snake’s morphology and image perspective supports a measurement closer to 6’/1.85 m. March was said to be 6’/1.85 m tall and invariably wore a tie in other surviving photos. His Honduran assistants also dressed exactly like this, sans necktie, so there is some question as to both the true identity of the person holding the snake, and their height. Image slightly enhanced from Ditmars (1931).

There is some controversy over the maximum size this species can achieve. The apparent record length for this species in Costa Rica and Panamá exceeds 7’/2.15 m (Solorzano, 2004; see below). Despite unconfirmed published reports indicating lengths over 8’/2.50 m that have become gospel among snake collectors for almost 100 years (see Ditmars, 1931; Ripa, 2002; and Savage, 2002 for three examples), a recent quick canvassing of a trio of New World herpetologists who are experts on this species and that included a review by one of them of almost 350 preserved specimens held in American museums revealed no Bothrops asper exceeding 6.70’/2.06 m in length (Lamar, pers. comm.). The largest female that I ever handled was just over 6.5’/2 m long and was collected in low elevation cloud forest at Finca Rosario Vista Hermosa on the Pacific slope of Guatemala’s Volcán de Agua in the Department of Escuintla. This locality also yielded several other very large female B. asper over the years. She fed well from the start, was fairly heavy bodied throughout and probably weighed in excess of 10 lbs/4.5 kg during much of her stay with me. I kept her in my study collection for several years before donating as a live specimen to a local university. The largest live animal I’ve ever seen was another huge female from Limón Province at the Universidad de Costa Rica’s venom lab, the Instituto Clodomiro Picado. Costa Rican herpetologist and author Alejandro Solorzano showed me this enormous if light bodied snake in the late 1980s. Because it fed indifferently at the time it was rather slender when I saw it, but the head was certainly the size of my fully outstretched palm. Alejandro subsequently put a tape measure on this exceptional individual towards the end of its life, and it measured 7.25’/2.23 m (Lamar, pers. comm.). This is, as far as I am aware, the longest B. asper reported by an unimpeachable source.

The classic grainy image, purportedly of Douglas March, taken in Lancetilla, Honduras in the late-1920s with what is claimed to be an eight-footer/2.45 m that is shown here in Ditmars (1931) is likely an intentional exaggeration and the relative size of the barba amarilla in the photo an artifice of foreshortened perspective. In my opinion, shared by others I know who have handled and photographed dozens of very large Bothrops asper, based on the snake’s rather small head size coupled with its girth, as well as compared with other images taken contemporaneously of different individuals posing with large B. asper at the same gate to the snake pit at the Serpentarium in Lancetilla (Balloffet, 2020), it is highly unlikely that this animal is much more than 6’/1.85 m long.

A recently-described pitviper species (Dal Vechio et al., 2021) from northern South America, a specimen of Bothrops oligobalius shown from Apoera, Suriname. This species is part of the widespread B. jararacussu complex and is very closely related to B. brazilii, which is shown lower in this article. In Amazonian Colombia, the Barasana people’s very apt name for this snake translates as “pile of ornate hawk-eagle feathers”. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2022.

Surprisingly, both my very large barba amarilla from Guatemala’s Pacific slope and the Instituto Clodomiro Picado’s enormous specimen from the Costa Rican Caribbean lowlands were both unflappable, non-confrontational and rather easy to handle for such a large and active venomous snake species. I cannot recall mine ever striking at me, even when taken outside in the sunlight and manipulated with a snake hook for photography and measurement. According to his comments, Alejandro Solorzano noted the same relatively calm behavior with the huge terciopelo he worked with for several years at the venom lab in Costa Rica.

Juvenile examples of this species may occasionally either gape with a half-opened mouth or coil and hide their heads when touched, two defensive behaviors also seen in other Mesoamerican crotaline snakes.

Shown above, two very distinctive color forms of the wide ranging and variable South American lancehead, common lancehead or Jergón (Bothrops atrox) from the Upper Amazon. This is the “other” pitviper species often called fer-de-lance. Snakes are shown in nature in the general vicinity of Iquitos, Maynas Province, Perú. Images: ©W. W. Lamar 2020.

Barba amarilla usually reach sexual maturity after about three years in captivity and very fortunate individuals may live 20 years or more in nature (Sasa, Wasko and Lamar, 2009). “Treadmill” fed captive female snakes can achieve imposing lengths in even shorter time spans, albeit accompanied by unnatural girths and overall appearances (Ripa, 2002).

A large South Brazilian lancehead or Jararaca-do-Cerrado (Bothrops moojeni) in nature, Goiás State, Brazil. This formidable pitviper species from central and southern Brazil together with adjacent regions of Paraguay and Argentina attains mature dimensions comparable to those of B. asper. Like other “fer-de-lance” it is easily provoked, highly venomous, and dangerous in close quarters. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2022.

Immobility is probably the least reported defensive response in crotalines when facing mammalian threats, but was reportedly the most common defensive behavior shown by South American rattlesnakes, Crotalus durissus facing predation in one study at the Instituto Butantan in São Paolo, Brazil (Almeida-Santos et al., 2000). I have two firsthand experiences where apparently healthy adult Bothrops asper have feigned death (thanatosis or tonic immobility) when confronted by humans.

On the first occasion, I was walking on a gravel railroad embankment at midday near Puerto Barrios, Izabal Department, Guatemala when I detected slight movement alongside the rails far ahead. I continued walking and finally came across a barba amarilla about 40”/1.0 m long, motionless and partially rolled on its side. I paused for a fairly close but superficial examination of the snake and, despite no sign of external injuries, it seemed quite dead. I assumed that it had been struck a glancing blow by a passing freight train or killed by some other shock earlier in the day. Without actually touching it with my sneaker shod foot or doing anything else rash, I started walking again. Continuing on for about 30’/9 m, I turned to glance back at it. To my astonishment the snake was slowly crossing the tracks with normal motion and no evidence of having been wounded, then sped up and fast disappeared over the side of the embankment and into the weeds as I returned. Perhaps it was just stunned when I found it and recovered immediately afterwards, but in light of the following event I don’t really think so.

The second case of one playing ‘possum involved a freshly captured captive Caribbean coast barba in my personal collection that was determined to have died overnight during the course of a routine late morning inspection by Haroldo García, my animal keeper. Haroldo had a great deal of experience manipulating both captive and wild native venomous reptiles, as well as exotic venomous snakes of many genera. He was, if such a thing is possible, generally overcautious in the way he handled hot snakes. He later swore up and down that he was extremely careful to ascertain that it was absolutely dead by shifting the Neodesha case it was in back and forth several times and seeing it flip upside down, limp and motionless. Haroldo then slid the door back, reached inside to remove it bare-handed and instantly received a full bite from the now obviously live and fully alert snake. He communicated all this to me in slow, painfully measured detail during an emergency call interrupting a heated business meeting I was in that then had me racing to a nearby private hospital to meet up with him and the 20 ampoules of Costa Rican polyvalent crotaline antivenin he had brought from the house. By the great grace of God, despite having received a full tag with both fangs on the base of his thumb by a ~4.5’/1.50 m newly caught Bothrops asper, it was a dry bite. My thoroughly chastened employee was discharged from hospital after eight hours of observation, a tetanus shot and bandaged thumb with nothing really wounded but his pride and my credit card.

The snake was, somewhat surprisingly to me, perfectly fine when I checked on it the next day and lived for more than a year afterwards.

A mature Bothrops asper lying in wait after dark in lowland rainforest at Finca La Selva, Heredia Province, Costa Rica. If I were asked to conjure up an image that embodied my encounters with this species in nature, this would be it. Hell’s Hole Punch, indeed! Mature terciopelos/barba amarillas and bushmasters at La Selva were the subject of a multi-year radio-tracking study in the late 1980s. Image transferred from 35 mm slide. ©W. W. Lamar 2021.

So, are barbas really as crazy cantankerous as many regional campesinos and some naturalists would have us believe?

Most times, probably not, since they’d be easy targets for avian predators or a machete if they lashed out madly at everything that passed by. Given their relative abundance in some areas, cryptic coloration and small size when coiled, it seems pretty obvious to me that many hundreds of thousands of rural people in northern Latin America must walk right by one every day without even seeing them, much less getting struck at. While I would say that those that I have come across during the day were generally, but not always, given to gliding quickly away when discovered, most large adults I have encountered after dark are altogether different creatures and whenever approached became–take your pick–a). visibly nervous, b). obviously testy, or c). borderline hysterical. In defense of these pitvipers’ responses, being suddenly confronted and confused with blinding light, strange tastes and smells in addition to the kind of vibrations that may herald the appearance of a large predator or other dangerous creature is enough to ruin anyone’s evening.

Cue main theme to “Close Encounters of the Third Kind”.

A large Bothrops asper from Panamá Province, Panamá. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2024.

Bill Lamar provides an anecdote on a face-to-face meeting with a big barba amarilla on the Colombian border with Panamá’s Darién Province that illustrates the danger these snakes can pose when feeling cornered and combative:

“…I was seated at water level near the stern in a long, extremely narrow motorized dugout with a small group of Emberá headed for their Resguardo Indígena to attend a meeting. We had left the Río Valle to ascend a small tributary, the Río Boroboro in the Chocó Department of Colombia. The forest was magnificent. It was dusk and almost too dark to see when we had to swerve hard to the border of the left bank in order to negotiate a narrow pass.

Abruptly the Emberá, one after another, leaned far to one side, away from the steep riverbank as the boat fought the current. Thinking perhaps there was a wasp nest there, I stared intently at the shore but saw nothing. Still, when my turn came, I leaned to the right just as they had.

This proved to be a very wise decision.

Suddenly a massive, beautifully patterned Bothrops asper, coiling and uncoiling, agitated and with head held high, materialized right in front of me. The pale markings stood out like a skeleton suit dancing in the gloom. And the snake didn’t just appear; it dominated the entire scene, as they tend to do. The lone Emberá behind me, operating the outboard, nearly capsized us as he dodged the irate pitviper. The looming canoe was a provocation, and a defensive strike would have hit home; fortunately, we passed it before that happened. Large lanceheads are prone to hang out along waterways and over the years I have found them commonly in such situations. But this encounter was invigorating, to say the least. I picked an excellent time to be a conformist.”

So just how fast can these snakes strike when they’re motivated? On many late afternoons I have watched relaxed subadult captive-raised bushmasters (Lachesis stenophrys and L. muta) softly twitch their heads in my direction when their enclosures were approached and, after I opened the doors, effortlessly snag dead rat pups I tossed to them off long forceps in mid-air. However, like a keyed up batter facing a set pose, these snakes knew the pitch was imminent so these aerial pickups, while quick and beautifully executed, were hardly remarkable.

A large South American bushmaster (Lachesis muta) in nature on the Río Nanay, northern Perú. This snake was estimated to be between 8-9’/2.5-2.8 m in length by the photographer, who has seen and handled many examples of all the bushmaster species under field conditions. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2022.

Personally, I consider bushmasters a bit slow when compared to the average healthy and alert adult barba amarilla.

Bill Lamar and Alejandro Solorzano were working one night in Piedras Blancas National Park in the Golfo Dulce region of southeastern Costa Rica when they head-lamped a mature Bothrops asper waiting by the trail with its head well raised and in full ambush pose. Bill had just picked up a large thin-toed frog (Leptodactylus savagei) and, with the snake fully illuminated and the men cloaked in darkness behind the lights, tossed it towards the snake.

To their complete shock, as the frog sailed into the pool of light, the terciopelo struck out instantly and caught it while it was still in the air.

Silence ensued (W. Lamar, pers. comm.).

A large, defiant and very alert Costa Rican terciopelo (Bothrops asper) in nature in Caribbean foothill forest, Limón Province. Image transferred from a 35 mm slide. ©W. W. Lamar 2021.

That, mae, is a hot snake that can strike both fast and accurately. Pray you never meet it when you’re wearing short pants and flip-flops on a dark and stormy night while on summer vacay in Costa Rica.

On the flip side of the realities of close association with these animals: I lived at an 800 acre/320 ha mostly forested site on the Caribbean coast of Guatemala in the Department of Izabal for about 18 months during the mid 1970s in an area that harbored fairly high numbers of Bothrops asper. Despite the abundance of this species on the property and snakebite from several venomous species being a quite common occurrence in the region–which was dominated by swamps, ranches, secondary forest and banana plantations–we never had an accident involving farm staff there although we did lose some very valuable livestock to bites by pitvipers, presumably barbas.

The short video clip shown below, filmed by nature guide Fred Muller in eastern Guatemalan lowland rainforest in 2019 and linked from my Vimeo account, shows two distinctive physical characters and one behavioral trait that illustrate the origins of three Spanish common names for this snake in Central America. First, the very conspicuous “yellow beard” (barba amarilla) when spotlit; second, the very deliberate “spooling” (devanador) reaction into a defensive coil against a buttressed tree and; third, the distinctly velvet (terciopelo) dorsal aspect of the snake evident when fully coiled at the end. The video also shows how, after having been first encountered out in the open on the forest floor, this individual deliberately retreated to a spot between two buttress roots of a canopy tree to make its stand. Sit and wait predators of all kinds often show clear and intimate familiarity with both favored ambush spots and refuges on their home range. This particular snake is obviously alert and situationally aware throughout the clip but the absence of non-stop tongue flicking and tail drumming shows that it is not overly alarmed despite both the spotlight fully on it and close proximity to Fred and companions.

Click to play.

The 25 plus year-old trend on television that has popularized supposedly telegenic jackasses showboaters free-handling dangerously venomous snakes in the field (usually in canned “capture” scenes staged beforehand by experienced animal wranglers for the camera) is, frankly, an irresponsible practice and has–no doubt–resulted in more than one amateur reptile buff and ecotourist getting tagged by a hot snake while emulating these buffoonish performances. This is all just sensationalist “reality nature TV” and there is nothing conservation-related about these scenes, despite marketing claims otherwise. Any interaction with venomous reptiles, even by very experienced field biologists and reptile keepers should, in my view, always call for: 1). real-time game theorizing the outcome of an animal’s probable behavior when facing capture, 2). one’s full attention at all times, and 3). possession of superb reflexes. I suppose it’s also worth noting here that–beyond frequent instances of hubris and idiocy–excess alcohol, recreational drugs and collections of captive venomous snakes are, in my past personal experience and current anecdotal accounts, a frequent and sometime tragic combination.

An Amazonian toad-headed pitviper, Bothrocophias hyoprora, along the Río Sucusari in northern Perú. A small, lowland species found in the Upper Amazonian rainforests of eastern Ecuador and Perú as well as western Brazil. Even small pitvipers are capable of inflicting fatal bites on humans. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2022.

Like contemporary nature TV heroes who have met unpleasant ends while engaged in foolhardy behaviors for the camera or on their day off, previous generations also lost their share of reckless snake handlers and zoo keepers who were likewise wildlife media darlings of their era. See Murphy & Jacques (2006) for an excellent profile of two well known “herpetologists”* from the 1950s and 1960s who both resulted with unexpected and acute cases of death after seriously pressing their luck with hot snakes for decades.

Among reptile collectors, it has long been known that inexpert pinning of large, heavy bodied but thin-necked snakes including adult examples of the larger pitviper species shown here can result in injury or death for the animal during the act or after the fact. Even when they do not suffer cervical vertebrae dislocations, it is always wildly stressful for these animals to be manipulated just to show off for companions or the camera. For us it’s just a casual thrill, but for them it’s very likely perceived as a life-threatening event and absolutely no fun at all. Although I am well aware and somewhat begrudgingly accept that reptiles and amphibia usually must be captured and posed to stage the “Dairy Queen” menu, “Vogue” cover, or “Indiana Jones” poster-style images sought by all, fieldworkers and photographers should exercise extreme caution when closely interacting with any venomous snake that has the size, personality, and toxicity to send you home in a casket à la Cal Academy of Sciences researcher Joseph Slowinski (Oliver/LA Times, 2001).

Just as foolish and slow self-styled “Elephant Whisperers” and other incautious on-holiday Bwanas sometimes become the pink stuff between the toes of short-tempered African elephants or in the teeth of lions who didn’t read the script, reckless and slow amateur venomous snake fanciers sometimes find out just how incredibly painful, debilitating, expensive or lethal a seriously hot snakebite can be today.

Better lucky than smart, I always say.

After working with well over a thousand dangerously venomous reptiles from around the world over a time frame spanning my early teens well into adulthood and having had at one time in the mid and late 1980s, one of the largest and most species diverse research collections of Neotropical pitvipers, coralsnakes, and venomous lizards anywhere (Slavens 1987-1989; Wille, 1992), I was never bitten by a venomous reptile.

A large adult pure yellow morph eyelash palm-pitviper (Bothriechis nigroadspersus) in the author’s collection in Guatemala, late 1980s. This particular color form of what is normally a greenish patterned snake species (see image of one at beginning of this article) pops up in lowland populations from southeastern Nicaragua, Limón Province in Costa Rica through to Bocas del Toro Province in western Panamá and is apparently unknown elsewhere. Eyelash palm-pitvipers are the world’s most variably colored snakes, ranging from creamy white to almost entirely black, with some individuals having rings, broad bands or partial stripes of contrasting colors (Arteaga et al., 2024; Reyes-Velasco, 2024; pers. obs.). This particular color phase is known in Costa Rica as the oropel (Fools’ Gold). It is a fairly small arboreal pitviper species mostly to around 24”/60m cm at maturity, although I kept an exceptionally large 40”/1.03 m specimen collected near Mariscos, Izabal Department, Guatemala for many years. Bites by this arboreal species, commonly made to the hands, forearms or faces of agricultural laborers in Costa Rica and Panamá, while only occasionally fatal, often result in loss of fingers or muscle tissue from necrosis or contracture. ©Author’s image scanned from a 35 mm slide.

A Brazil’s lancehead, Bothrops brazili, Junín Province, Perú. This medium-sized pitviper has a very wide distribution across northern South America. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2022.

Full disclosure, I once impaled my right index finger on a single extended fang of a young yellow eyelash palm-pitviper (Bothriechis nigroadspersus) while administering anti-parasitic medication via catheter. Fortunately, this accident produced no symptoms other than a brief bout of anxiety and rather free bleeding from the puncture site. I attribute my near perfect score over more than 20 years to having always believed facing these snakes required intense focus at all times, that they are best manipulated with instruments like aluminum hooks, softly-employed grabsticks, endoscopic forceps or clear plastic control tubes whenever feasible and NEVER left to roam free on the floor while you work around them. Luck certainly plays a huge role in terms of final score. Every single friend and acquaintance I have that has worked with hot snakes, some far more skilled than me, has experienced a moderate to severe bite, always while handling them. This includes some very famous and respected herpetologists, reptile dealers, zoo employees, venom lab workers and wildlife photographers as well as garden variety bozos who interact/ed with venomous reptiles. Unsurprisingly (to me, at least), despite all of us having spent a combined hundreds of thousands of man hours in the field searching for reptiles around the world, off the top of my head, no-one that I know personally has ever been bitten by an unrestrained wild front-fanged snake.

Proper safe handling of venomous reptiles on a regular basis is a technique that takes time to perfect and is often developed the hard way**. Certainly, I’ve had my share of very close calls both trying to capture wild snakes in nature and handling fast, flighty captives during medical evaluations or cage maintenance so, again, better lucky than smart.

“As a professional venomous snake handler, the other extreme was Douglas March.”

Did I say “big front teeth”? Where the rubber hits the road for many unlucky rural people in lowland Mesoamerica, Colombia, and Ecuador as well as for a few careless herpetologists working with Bothrops asper. Image: © F. Muller 2020.

One of the people who generally impressed me as a very careful venomous snake handler during the time I interacted with him is Alejandro Solorzano of San José, Costa Rica. When I first met Alejandro during the mid 1980s, he was an assistant researcher and lab technician in charge of extracting venom from live native snakes held at the Universidad de Costa Rica’s facility in Coronado that produced antivenin for regional crotaline and coral snakes. At that time, during any given active month he probably manipulated more dangerously venomous snakes with his bare hands than most major zoo reptile keepers do in a decade.

While we were friends, he had his first and hopefully last (?) envenomation involving a medium-sized Bothrops asper that, while thrashing about while being milked, squirmed partially free from his grip then stabbed him deep in a finger before he could get it free from his hands. Probably because the fang was bathed with fresh venom along its entire length this was, for all intents and purposes, probably equivalent to a moderate bite by a young snake. Despite being in excellent physical condition and having freshly prepared, refrigerated polyvalent antivenin at hand, during the relatively short interlude between the envenomation and emergency medical care counteracting its effect, he described the pain as being both almost unbearable and physically devastating. Notwithstanding his best efforts to tough it out in front of both his doctors and his father, who arrived on the scene shortly following notification his son had been bitten, Alejandro told me that tears of indescribable pain streamed down his face constantly for more than half an hour.

Far from “Familiarity breeds contempt”, in my opinion close daily interaction with venomous snakes should inspire ever increased caution and respect for both their capacity to inflict a serious or fatal injury and the growing odds against you avoiding a costly slipup as time goes by.

As a professional venomous snake handler, the other extreme was Douglas March. March was a U.S. amateur reptile collector that embarked New Jersey for northern Central America at the beginning of the 1920s. His name emerges frequently in early 20th century Central American herpetological accounts, largely due to his connections with friends Raymond Ditmars of the Bronx Zoo and Dr. Thomas Barbour of Harvard University. Both well-respected scientists championed his management of the Serpentarium and venom extraction facility run by United Fruit’s Tela Railroad Company and Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology at Lancetilla, Honduras. Douglas March was by all accounts more a thrill-seeker and foolhardy adventurer than serious herpetologist, but he certainly did enjoy interacting with hot snakes. Ditmars, hardly a shrinking violet when it came to handling venomous reptiles, was reportedly a bit shaken after seeing him at work:

“The Tela serpentarium’s young manager regularly descended by ladder into his serpent pit to collect venom from the dreaded barba amarilla vipers, a duty he relished. Clad in high leggings, the fearless Pennsylvanian would descend into the pits among a hundred or more venomous serpents, brazenly free handling them to extract their venom. A recent accident with a barba amarilla, leaving March partially blind until serum could be administered, failed to temper his reckless behaviour.” (Eatherley, 2015).

When a snake handler’s luck finally runs out and Atropos snips the thread. Courtesy of Bothrops asper, a copy of Douglas March’s death certificate issued by the U.S. Consul in Panamá in 1939. Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2022.

Some of March’s more noteworthy claims have not stood the test of time, to say the least. In a short paper drawn from field notes and published in 1928, March wrote that the barba amarilla’s reputation was “somewhat exaggerated”. He moved to the Canal Zone in Panamá in 1933, apparently assumed the title “Doctor” and started his own serpentarium in what is now the Casco Viejo in Panamá City. It is reported that he was bitten 17 times by venomous New World snakes prior to his final accident. He misjudged the lethality of his subject matter on one too many occasions and ultimately died in 1939 at age 52 from a Bothrops asper bite in Panamá.

Yet another Gringo who had to find out the hard way.

A warning note on the two open mouth Bothrops asper photos shown up top. It can be tricky to restrain some species of slender, long-fanged vipers with a three-fingered hold on the head in a natural setting if they are thrashing around and constant attention is not paid to correct finger placement while proper pressure maintained throughout. Plenty of very experienced reptile handlers around the world have been finger stabbed and envenomated by frightened or enraged vipers doing just this. While the photographs shown are, in my opinion, well composed and of great visual impact, it would be incredibly foolhardy for almost anyone to attempt to duplicate them - so please don’t.

Additional Disclaimer: After having interacted for decades on a personal basis with research taxonomists, museum herpetologists, zookeepers, venom lab workers, field biologists, and private collectors who kept captive venomous snakes in their homes and places of employment, and after seeing how some handled and cared for their animals, I am now firmly opposed to unregulated private ownership of venomous snakes as “pets”. These animals are all potential “widow-makers” in the truest sense. I particularly dislike the notion that flighty, hard-to-handle, extremely toxic large elapids and exotic crotalines are legally available for purchase by almost any halfwit in some areas. In the U.S. and the EU, one would think that the potentially catastrophic legal liability alone would curb people’s appetites to own them, but no. If one escapes and kills a neighbor’s child, the guilty collector will likely be both emotionally and financially bankrupted for life. Indeed, in today’s crazed media environment and the prosecutorial zeal it whips up, they may even end up in jail for a prolonged stint for criminal negligence.

This article in no way promotes nor endorses private ownership nor free-handling of venomous snakes anywhere in the world.

An Incan forest-pitviper (Bothrops [Bothriopsis] chloromelas). Image: ©W. W. Lamar 2022.

Acknowledgements

Thanks again to ecotour guide and photographer Fred Muller for capturing many beautiful images of Bothrops asper and other venomous snake species in nature across México, Central America, Panamá, and Perú, sometimes at considerable personal risk. Renowned herpetologist, natural history guide, author, photographer, fellow Esotérico, and all-round “complex guy” William Lamar graciously consented to read parts of this article in late draft form, added many great photos of Lachesis muta together with unusually colored Bothrops, Bothriopsis and Bothrocophias species, as well as providing the copy of Douglas March’s death certificate shown above. Bill also shared a number of his own observations and thoughts on Bothrops asper behavior in the field across northern tropical America and canvassed his colleagues in Costa Rica for their opinions on this snake’s true maximum length.

*Rather curiously, somewhere along the line reptile keepers with no scientific training became “herpetologists” to journalists, while canary keepers never became “ornithologists”, nor goldfish keepers “ichthyologists”.

**In 2015, Fred Muller opted for “the hard way”. This is a link that summarizes his experience after briefly touching a (very) live and short-tempered Eastern variable coral snake (Micrurus apiatus) in northern Guatemala, and posted on his Flickr page just afterwards: https://www.flickr.com/photos/fredmullerpix/20525430326/

Eastern Guatemalan barba amarilla (Bothrops asper) showing cryptic dorsal coloration on the forest floor. Image: ©F. Muller 2020.

References Cited

Almeida-Santos, S. M., M. M. Antoniazzi, O. A. Sant’Anna and C. Jared. 2000. Predation by the opossum Didelphis marsupialis on the Rattlesnake Crotalus durissus. Current Herpetology 19 (1): 1-9.

Aragón, F. and Gubensek, F. 1981. Bothrops asper Venom from the Atlantic and Pacific Zones of Costa Rica. Toxicon 19 (6): 797-805.

Arteaga, A., A. Pyron, A. Batista, J. Vieira, E. Meneses Pelayo, E. N. Smith, C. L. Barrio Amorós, C. Koch, S. Agne, J. Valencia, L. Bustamante and K. Harris. 2024. Systematic Revision of the Eyelash Pitviper Bothriechis schlegelii (Serpentes: Viperidae), with the description of five new species the revalidation of three. Evolutionary Systematics 8 (1): 15-64.

Balloffet, L. P. 2020. Venomous Company: Snakes and Agribusiness in Honduras. Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2020), No .19.

Campbell, J. A. and W. W. Lamar. 1989.The Venomous Reptiles of Latin America. Comstock, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY. 425 pp.

Campbell, J. A. and W. W. Lamar. 2004. The Venomous Reptiles of the Western Hemisphere. Two Volumes. Comstock, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY. 774 pp.

Chandler, R. 1939. The Big Sleep. Alfred A. Knopf. 277 pp.

Chandler, R. 1950. The Simple Art of Murder. Houghton Mifflin Co. 384 pp.

Chandler, R. 1953. The Long Goodbye. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 320 pp.

Chippaux, J-P. 2017. Incidence and mortality due to snakebite in the Americas. PloS Negl. Trop. Dis. 11 (6).

Conan Doyle, A. 1892. A. The Adventure of the Speckled Band. Strand Magazine, George Newnes Ltd, London.

D’Amelio, F., H. Vigerelli, A. R. de Brandão Prieto da Silva and I. Kirkis. 2021. Bothrops moojeni venom and its components - an overview. J. Venom Res. Vol. 11, 26-33.

Dal Vechio, F., I. Prates, F. G. Grazziotin, R. Grabowski and M. T. Trefaut. 2021. Molecular and phenotypic data reveal a new Amazonian pit vipers (Serpentes: Viperidae: Bothrops). J. Natural Hist. 54 (37-38): 2415-2437

Ditmars, R. L. 1931. Snakes of the World. The MacMillan Co., NY. 207 pp. + 84 plates.

Eatherley, D. 2015. Bushmaster: Raymond Ditmars and the Hunt for the World’s Largest Viper. Arcade. 320 pp.

Gutiérrez, J. M. 2014. Current challenges for confronting the public health problem of snakebite envenoming in Central America. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 20, 7.

Hardy, D. L. 1994. Bothrops asper (Viperidae) Snakebite and Field Researchers in Middle America. Biotropica, Vol. 26 (2): 198-207.

Laínez-Mejía, J.L., Barahona-López, D. M., Sánchez-Sierra, L. E. Matute-Martínez, C.F., Cordova-Avila, C.N. and Perdomo-Vaquero, R. 2017. Caracterización de Pacientes con Mordedura de Serpiente Atendidos en Hospital Tela, Atlántida. Rev. Fac. Cienc. Méd. Honduras, Enero-Junio 2017. 9-17.

March, D. D. H. 1928. Field Notes on the Barba Amarilla (Bothrops atrox). Bulletin, Antivenin Institute of the Americas. I:92-97.

Murphy, J. B. and D.E. Jacques. 2006. Death from Snakebite: The Intertwined Histories of Grace Olive Wiley and Wesley H. Dickinson. Bull. Chicago Herp. Soc., Special Supplement. 1-20.

Nations, J. D. 2006. The Maya tropical forest: People, parks and ancient cities. University of Austin Press, Austin, TX. 368 pp.

Oliver, M. 2001. J. Slowinski, 38; Snake Expert is Bitten, Dies. Los Angeles Times. September 20, 2001.

Pecchio, M., Suárez, J. A., Hesse, S., Hersch, A. M. and Gundacker N. D. 2018. Descriptive epidemiology of snakebites in the Veraguas province of Panama, 2007-2008. Trans. Royal Society of Trop. Med. And Hygiene. Vol. 112 (10): 463-466.

Reyes-Velasco, J. 2024. A revision of recent taxonomic changes to the eyelash palm-pitviper (Serpentes, Viperidae, Bothriechis schlegelii). Herpetozoa. 305-318.

Ripa, D. 2002. The Bushmasters (Genus Lachesis Daudin, 1803). Morphology in Evolution and Behavior. Second Edition. Cape Fear Serpentarium, Wilmington, NC. 358 pp.

Saldarriaga-Córdoba, M., Parkinson, C. L., Daza, J. M., Wüster and Sasa, M. 2017. Phylogeography of the Central American lancehead Bothrops asper (Serpentes: Viperidae). PloS ONE 12 (11)

Sasa, M., Wasko D. K. and Lamar, W. W. 2009. Natural history of the terciopelo Bothrops asper (Serpientes: Viperidae) in Costa Rica. Toxicon 54, 904-922.

Savage, J. M. 2002. The Amphibians and Reptiles of Costa Rica: A Herpetofauna Between Two Continents, Between Two Seas. University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London. 934 pp + 516 plates.

Slavens, F. L. 1987, 1988, 1989. Inventory of Live Reptiles and Amphibians in Captivity. Frank L. Slavens, Seattle, Wa.

Solorzano, A. 2004. Snakes of Costa Rica: Distribution, Taxonomy, and Natural History. INBio., Costa Rica. 792 pp.

Stout, R. 1916. The Last Drive. Golfers Magazine (serialized). 104 pp.

Stout, R. 1934. Fer-de-lance. Farrar & Rinehart. New York. 313 pp.

Tumang-Frare, B., Silva Resende, Y.K, de Carvalho Dornelas, B., Jorge, M. T., Souza Ricarte, V. A., Alves, L.M. and Moreira Izidorom L.F. 2019. Clinical, Laboratory and Therapeutic Aspects of Crotalus durissus (South American Rattlesnake) Victims: A Literature Review. Biomed. Res. Int. (2019).

Vega-Coto, J., D. Ramírez-Arce, W. Baaijen, A. Artavia-León and A. Zuñiga. 2015. Bothrops asper. Arboreal Behavior. Mesoamerican Herpetology. Volume 2. Number 2. Pp. 199-201.

Wasko, D. K. and Sasa, M. 2009. Activity patterns of a Neotropical ambush predator: spatial ecology of the fer-de-lance (Bothrops asper, Serpentes: Viperidae) in Costa Rica. Biotropica 41, 241-249.

World Health Organization (WHO). 2019. Snakebite Envenoming. Health Topics.

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC® 2020-2025, ©Fred Muller 2020, and ©William W. Lamar 2020.

A regional Bothrops asper mimic, the false fer-de-lance (Xenododon rabdocephalus). It is a wide ranging, small to medium-sized (<32”/80 cm) rear-fanged snake species whose bite may occasionally cause localized discomfort and swelling. This otherwise inoffensive frog and toad-eating colubrid is doing its very best here to look like an angry barba amarilla. Image: ©F. Muller 2020.