Ozempic® Nation

Among the Nose Bros of Año Nuevo: Slim Seals Fast

By Jay Vannini

A study in gray on a foggy morning. Subadult male northern elephant seals, Mirounga angustirostris, looking trim at Bight Beach while fasting during the mid-summer molt at Año Nuevo State Park, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024

Backyard wildlife, Esotérico-style

Both of my fellow contributors to this website are smart and fortunate enough to live adjacent to areas of serious interest to biologists, nature photographers, and ecotourists. Peter Rockstroh resides in Bogotá, Colombia flanked by two of the largest páramos in the world (Chingaza and Sumapaz), with montane cloud forest nearby and surprisingly good birding to be had from the comfort of his terrace. William Lamar has a home in rural northeast Texas as well as in Iquitos, Perú, so is also out exploring and photographing some mighty fine and diverse ecosystems most of the time.

Because of the tropical bias of Exotica Esoterica I have given admittedly short shrift to the wildlife and wildlands in my area. For reference, after almost 40 years residence in Central America I currently live midway down the San Francisco Peninsula, and have a large, protected salt marsh and estuary located about a 15 minute stroll up the street. During the fall and winter migrations this area is visited by large numbers of seabirds, shorebirds, wading birds, and waterfowl, as well as noteworthy avian predators such as resident and tundra peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus anatum and F. p. tundrius), as well as the occasional merlin (F. columbarius), and northern bald eagle (Haliaeetus l. leucocephalus). Green herons (Butorides virescens), Cooper’s hawks (Accipiter cooperi), and a couple owl species breed in the older trees around my home and nearby park. Despite considerable fragmentation and contamination of natural ecosystems clearly evident throughout the San Francisco Bay area, its wildlife is surprisingly varied and conspicuous if you pay even the slightest attention to the world around you.

A small sample of migrant duck diversity at low tide along a slough on the salt marsh located less than half mile/800 m from my front door. Canvasbacks Aythya valisineria; pintails, Anas acuta; shovellers, Spatula clypeata; and ruddy ducks, Oxyura jamaicensis, are visible in this image, taken while on a walk late one December afternoon a couple years back. Not shown in the image are another three migrant duck species that were paddling the slough 50 yards/m away. Peak waterfowl diversity on this marsh during the fall migration is definitely impressive, numbering many thousands of aquatic birds at a single spot that occasionally includes an Old World vagrant (pers. obs.). Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

The previous article posted here, with Bill Lamar’s observations on a backyard western ribbonsnake (Thamnophis proximus) – a mature gravid female – offered promising evidence of a nascent recovery of a population of this species on his property. It touches on hands-on wildlife management if only at a micro level (i.e., fire ant eradication on his property; a link to the article is provided below). This thoughtful essay set the wheels in motion for me to get off my duff and take a closer look at some of my wildlife neighbors that have likewise benefited from active conservation/preservation and management measures.

With plenty of interesting subjects to choose from and having been born in Texas, I immediately gravitated towards the largest and the loudest.

Les presento al elefante marino norteño (Mirounga angustirostris).

Mature bull northern elephant seals seeking to intimidate each other prior to a skirmish at Año Nuevo State Park. Note the heavily scarred neck “bibs” that build up with age and over the course of fierce territorial fights with rivals. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

A bit of relevant 19th century history

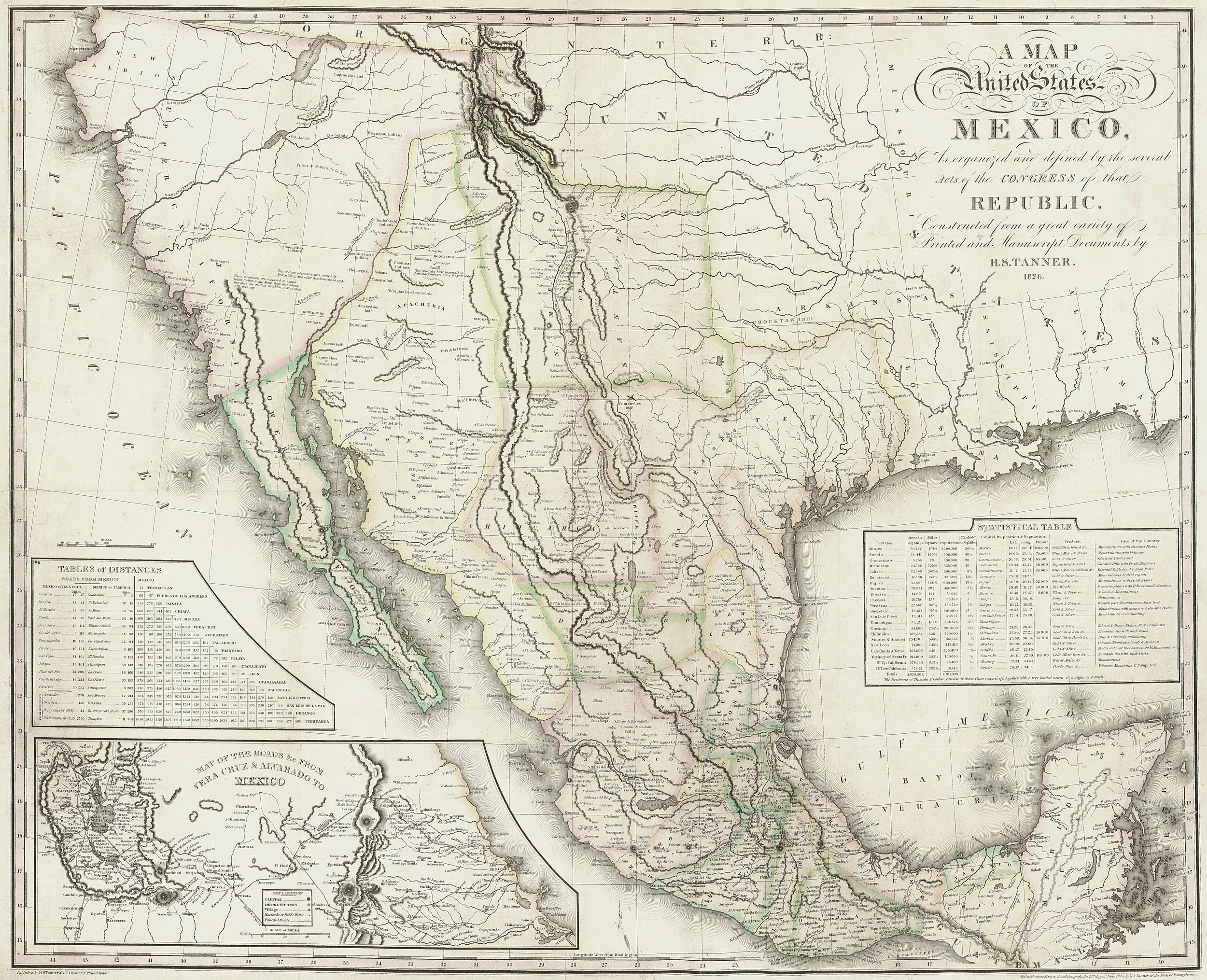

One enormous but often overlooked benefit of the United States of America’s victory in the Mexican-American War and the resulting Guadalupe-Hidalgo Treaty of 1848 wherein México was obliged to cede more than half of its land mass, was the staggering increase in biological diversity and other valuable natural resources* that the U.S.A. accrued to its benefit. Aside from subtropical Florida, biodiversity in the temperate terrestrial ecosystems that comprised the U.S.A. in 1847 may – broadly speaking – be compared with that of contemporary western Europe.

So, while hardly a turnip patch by any stretch, prior to the territorial gains extracted from the ratification of Guadalupe-Hidalgo and the subsequent Gadsden Purchase of 1854, the United States of America of that time was not exactly Borneo nor Brazil in terms of biodiversity.

The annexation of Alta California and territories further east added the vast scenic landscapes now part of the U.S.A.’s West, their associated Native American cultures, together with rich biotas that are interwoven into its citizens’ national identity, appreciation of Big Sky wilderness (in word, if not in deed), and widespread worship of frontier mystique and mythology.

A map of the United States of México in 1826, prior to annexation of Soconusco in the southeast in 1842, and loss of all territories in the north a few years later to the United States of America during the Mexican-American War and the Gadsden Purchase. The present-day U.S.A. states of Texas and California marked the northern, eastern, and western boundaries of México in North America until 1848. This map is of particular interest since it shows, in detail, the geographical location of the different native communities populating México at the time. Point Año Nuevo is identified along the coast just southwest of San Francisco on the upper left of the map, with Guadalupe (Island) shown lower down and well offshore. Non-copyrighted image credit: Digital Commons. Pre-1846 Maps, Map 10. digitalcommons.csumb.edu.

Needless to say, reality clashed with romantic notions of wilderness exploration and preservation from the git-go. Ever since the rich windfall reaped from Guadalupe-Hidalgo landed in its lap, U.S.A. political and commercial interests have waged almost continuous war on the original ecosystems of what became its western states, their native human inhabitants, and the remarkable species of plants and animals that lived there.

One of the many mammalian victims of 175 years of constant drive-by shootings that subsequently ensued was the northern elephant seal. This outsized pinniped was hunted relentlessly for its blubber to produce high quality seal oil and extirpated as a U.S.A. breeding species on southern California’s Channel Islands by sealers and whalers during the 1850s. For the next 70+ years the few remaining offshore colonies in Baja California in northwestern México remained under constant pressure by both sealers and museum collectors, each apparently Hell-bent on getting “that last one”.

Rather surprisingly given that fact, this particular story has a happy ending.

At least for now.

Flowering Yadon’s rein orchid, Platanthera yadonii, an endangered microendemic terrestrial orchid species that is restricted to coastal forests of northern Monterey County, California. Many populations of California plants with restricted distributions are threatened by development and changing climate patterns. Image: ©Ron Parsons 2024.

The Promised Land

Among the most arresting panoramas of the North American West are those located along U.S.A. California’s 840 miles/1,350 km of coastline. The formidable geographical relief, rich littoral and offshore ecosystems that are the product of regional biogeography, warm inland climates much of the year, and the cold water, nutrient rich California Current flowing offshore showcase a numerous and complex set of communities of flora and fauna. Many species in this region, but especially plants, are narrow endemics.

Marine mammal colonies are a conspicuous feature of many scenic California coastal areas. Preservation efforts implemented over the past century by state, Federal, and Mexican authorities have led to a resurgence in breeding numbers of seals (two species), sea lions (two species), fur seals (two species), and southern sea otters (Enhydra lutris nereis – although recent population trends are uneven).

Numbers of California sea lions (Zalophus c. californianus), Steller’s sea lions (Eumetopius jubatus), and Pacific harbor seals (Phoca vitulina richardsii) have, in fact, increased to levels where human-pinniped conflicts have become commonplace. Predictably, this has led for calls by indigenous people, commercial interests, fishery managers, and some recreational anglers to permit culls/euthanasia of nuisance individuals or populations, especially where spawning salmon, steelhead, and sturgeon are involved. Changes to the Marine Mammal Protection Act in 1994 (under Section 120 [f]) permit lethal removal of “problem” sea lions of both native species in Washington and Oregon (NOAA, 2024a).

Among some conservationists and animal rights groups these measures are controversial, to say the least.

Adult harbor seals, Phoca vitulina richardsii, resting on offshore rocks at Pescadero State Park, San Mateo County. Image: ©Ron Parsons 2024.

Even the most cursory examination of the history of human exploitation of sea otter, pinniped (walruses, earless seals, and eared seals), and cetacean (whales and dolphins) populations on the west coast of North America will reveal repetitive and depressing preambles such as, “Hunted almost to extinction…”, or “Once believed extinct due to overhunting…”, etc. Despite this, the recoveries of many populations of marine mammals since their nadirs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries are nothing short of miraculous. They are a tribute to boots & guns preservation measures first implemented by the Mexican government on Guadalupe Island, Baja California Norte in 1922, followed by the U.S.A. in the following decades.

Northern elephant seals

One of the most famous cases of one of these stick saves in final play is that of the northern elephant seal. Genetic models suggest that it was likely reduced to as few as 10-20 individuals in México by the 1890s (Hoelzel et al. 1993; Le Boeuf et al., 2011). The population began recovery early on and has shown a steady upward trendline to a current population of ca. 220,000 individuals at 21 active breeding sites in Baja California and the U.S.A. state of California, coupled with fairly recent reports of sporadic breeding events at Shell Island, Oregon, an offshore site distant from the northernmost mainland rookery at Point Reyes National Seashore (Hodder et al., 1998; Le Boeuf et al., 2011; Le Boeuf et al., 2019; NOAA, 2021 [2022]; Hoelzel et al., 2024; anon. pers. comm.).

There is a colossal (intimidating, even?) amount of interesting, extensively-researched, peer-reviewed publications available online via simple search that discuss the population growth, morphology, and ecology of northern elephant seal populations. Some of it is listed in the reference section below. I’ll forego lip-synching the content of these articles and give the executive summary from Le Boeuf et al. (2011), Torben et al. (2011), and others (NOAA, 2024b).

Substantially outclassed in overall size by their southern cousins (Mirounga leonina), northern elephant seals are still noticeably bigger than a breadbox. Mature males can exceed 15’/4.6 m in length and 5,000 lb./2,250 kg in weight. Besides the signature floppy schnozzes carried by adult males, they are equipped with a serious set of long, if blunt, choppers. Watching a pair of large bulls going at it hammer and tongs in territorial disputes close-up is a memorable experience (pers. obs.).

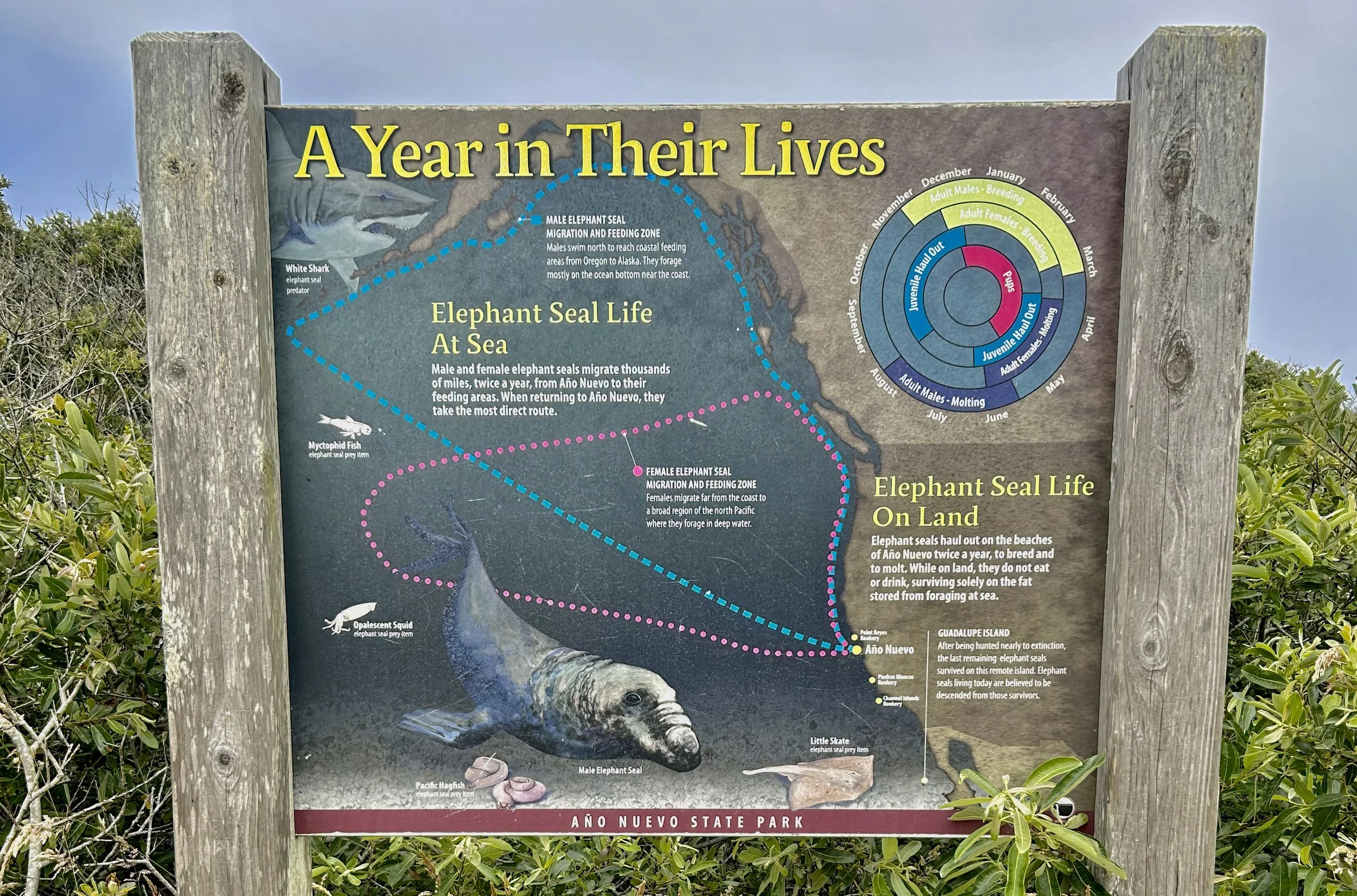

Mature northern elephant seals effect long distance migrations four times annually; once from breeding beaches in winter to feeding grounds further north and west, back to home beaches to molt in late spring and summer, then a return to their feeding grounds, followed by their return to main rookeries in winter to complete the cycle.

The annual molt involves different sexes and age classes arriving on the beaches at Año Nuevo at different times. Mature females arrive in late April and May, followed by subadult males in June, which overlap with the arrival of mature bulls in early and mid-July. Juveniles are on the beach at Año Nuevo together with mature females.

All of the animals I photographed for this article during two visits in July 2024 are young to fully mature males, so the beach parties were definitely stag events. The image of a female haul out shown immediately below was taken by Ron Parsons a few years back at a different rookery located further south. The images of marine mammals shown in this article were taken with long telephoto lenses from permitted viewing areas and no close approaches to the animals occurred.

Adult female elephant seals on the beach in early June during the molt at San Simeon, San Luis Obispo County. Image: ©Ron Parsons 2024.

Two subadult male elephant seals sparring on the beach in early July at North Point, Año Nuevo. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Large bull elephant seals sleeping on Bight Beach, Año Nuevo during late July. Crows in the background are scavenging a seal carcass. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

For a mammal, among the many extraordinary feats that mature elephant seals are capable of include record-breaking deep dives into the abyss, periodic long distance migrations from coast to open ocean and back, serious breath-holding abilities while submerged, and adaptations that allow for extremely loud vocalizations. One of the more interesting aspects of their natural history is the huge weight loss that occurs while fasting during time on land molting and breeding. While on the beach during breeding aggregations as well as while molting the coats, the seals obtain nutrition and water via metabolizing their blubber reserves. Elephant seals can lose more than one-third of their arrival weights during these extended fasts (NOAA, 2024b).

Below, a sequence of images showing a serious skirmish between two bull elephant seals at Año Nuevo in late July. Fights among males during the molting season are rare (anon., pers. comm.) and this one began out of the blue, instigated by the smaller male shown bellowing in the first frame. The fight did involve some fairly serious biting of front flippers and necks by both as shown below but I saw little blood. It ended following the last frame here, with the smaller bull suddenly turning tail and fleeing off towards the island. All images: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Conversely, they replenish blubber reserves while at sea where they feed for most of the 24 hour cycle despite the considerable physiological challenges that this poses for the seals (Adachi et al., 2021). Their prey consists mainly of deep water squid and bottom-dwelling fishes.

Elephant seals really are world champion yo-yo dieters but have relatively short lifespans for a large mammal, especially the males. There is a lesson about the risk and benefits of extreme fasting in there somewhere…

Northern elephant seals share their eastern and north Pacific range with a number of known or potential predators, including white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias), shortfin mako sharks (Isurus oxyrinchus), Pacific sleeper sharks (Somniosus pacificus), and orcas (Orcinus orca). Of these, white sharks are almost certainly their most important predator by a wide margin, followed by orcas. Large tiger sharks (Galeocerdus cuvier) are rarely reported in U.S.A. Californian waters but are more common in the Mexican state of Baja California Sur (BCS), are known to prey on monk seals (Monachus schauinslandi) in Hawaii (Wetherbee et al. 2024), and reportedly prey on California sea lions at a colony located near Cabo Pulmo, BCS (anon. local dive guide, pers. comm. [1997]). Tiger sharks may be a candidate predator of northern elephant seals at inshore localities, at least occasionally in some areas. Elephant seals are also subject to occasional parasitic attacks by cookiecutter sharks (Isistius brasiliensis) as evidenced by scars observed on beached individuals, including some recorded at Año Nuevo (Ebert & Pien, 2015; NOAA, 2022; anon., pers. comm). Mortality from predation that occurs throughout their lives is believed to be high.

White shark and northern elephant seal interactions are of obvious interest to researchers, videographers, and laypersons alike. Unlike sea lions and fur seals, other than surfacing to breathe or approaching land, elephant seals mostly travel underwater, including near the bottom during dispersal off the beach and while feeding in both pelagic and coastal environments (Adachi, et al. 2021; anon, pers. comm.). Given this fact, we can reasonably assume that most predation events occur at depths where humans don’t observe them. During subsurface encounters with large white sharks where the seals have detected the predator at any distance, they may have evasion strategies that are mostly unavailable once they have been attacked while briefly on the surface. Sean Van Sommeran, the noted white shark expert and conservationist at the Pelagic Shark Research Foundation, has observed that Californian elephant seals and white sharks may occasionally engage in what he has called “fencing” during predation events that likely results in most of these defensive seals being caught and killed (Van Sommeran, 2005; anon., pers. comm.). Predation of elephant seals by white sharks that begin as submarine encounters occasionally become evident to human observers in boats or looking on from coastal outlooks when the seals surface bleeding heavily following incapacitating abdominal or thoracic bites. From this stage it either escapes or is dealt a coup de grâce and is consumed by the shark/s. See Table 1. in Le Boeuf et al. (1982) for evidence suggesting that large white sharks are capable of decapitating bites on sizeable elephant seals.

Above, a four and a half year-old subadult male northern elephant seal on the beach at Año Nuevo in early July 2024 showing evidence of a white shark bite it received approximately 10 months prior (anon., pers. comm.). Tissue scarring from the bite/teeth are clearly visible on the seal’s lower back (left) and abdomen (right). Dyed numbers indicate that this individual is being monitored by researchers working at Año Nuevo. Images: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Where from here?

Despite the conservation success of northern elephant seals following a near-extinction event caused by over-hunting more than a century ago, new risks remain for the species. Entanglement with commercial fishing gear by both species of elephant seals is well documented throughout their ranges. Together with entanglement, accidental collaring, and ingestion of plastic debris are well-known and growing threats to marine fauna everywhere.

A 2023 outbreak of deadly H5N1 avian influenza at a globally important southern elephant seal colony located on the Valdés Peninsula in Argentina produced near total mortality in pups on the beach, with associated mortality in adults at lower incidence levels. Influenza H5NI is believed to have arrived in South America in 2022 and has decimated other pinniped stocks there (Campagna et al., 2023 [2024]; Uhart et al., 2024). Given these mass die-off events, coupled with confirmed 2023 reports of HPAI H5NI in avian populations of waterfowl, wading, and seabirds in southern U.S.A. California, there is understandable concern about its potential impact on northern elephant seals throughout their range (anon., pers. comm.).

Año Nuevo State Park

Año Nuevo State Park is a 4,200 acre/1,700 ha nature reserve located near the exact center of California’s coastline. Heading south, it is the second to last of a string of scenic state beaches, marine conservation areas, and nature reserves that dot the coast between San Francisco and Santa Cruz. It is also part of the University of California’s Natural Reserve System (UCNRS, 2024; anon, pers. comm.).

Año Nuevo Island seen from near Point Año Nuevo. At this spot it lies just over a half mile/~800 m offshore. The island reserve covers a surface area of ca. 9 acres/3.65 ha and has access restricted to park staff and approved researchers. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

The beach at North Point at Año Nuevo State Park. Subadult male and mature bull elephant seals hauled out during the molt in early July 2024 are visible upper right. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

The park was established in 1985 and incorporated the Anõ Nuevo State Nature Preserve in 2008. It is an easy one hour drive from my home to the park entrance during weekdays. After spending a couple days wandering the park last month – after carefully timing my visits to coincide with fine late morning weather and reduced vehicle traffic throughout the commute – I kept asking myself why I don’t spend more time there?

Small protected areas and tiny urban green spaces are sometimes referred to as “pocket parks”. With this concept in mind, I would call Año Nuevo State Park a “jewel box reserve”.

Looking east (or left center in the photo) towards Cove Beach, a public area popular with local surfers. State Route 1, better known in this area as the Cabrillo Highway, is also visible in the distance running south along the shore towards Santa Cruz. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Northern elephant seals were first observed visiting Año Nuevo Island in 1955 and established a small breeding colony on the island in the early 1960s prior to establishing the rookery on the adjacent mainland beach in the mid-1970s. While not as large as the offshore rookeries on the Channel Islands and two breeding beaches located alongside State Route 1 in San Luis Obispo County, the proximity of the University of California Santa Cruz to Año Nuevo State Park has made it one of most/the most important centers for elephant seal field research in the state.

Feeding adult southern sea otter, Enhydra lutris nereis, photographed at a distance floating between Bight Beach and Año Nuevo Island in early July. This is considered the northern end of this subspecies’ current range. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Anyone who is interested in nature in California and has the opportunity should make an effort to visit this park at least once during the winter breeding season to view the northern elephant seal colony at full strength. Weather at that time of the year can be a bit uncertain for sure, and cool, windy (very), foggy, or rainy days are the norm during much of the elephant seal breeding season. Access to the park during the fall and winter seasons is restricted to guided tours only, and may require reservations. I vastly prefer visiting in the summer months despite seal numbers being measured in the hundreds, rather than the thousands. Freedom to wander the trails at one’s own pace, coupled with the combination of wildflower blooms and sunny days, the pinnipeds on the beach, and a chance to glimpse sea otters foraging just offshore make it a compelling destination.

Criticism of Californian political institutions is again in vogue, and lampooning many state and local bureaucracies is low-hanging fruit for humorists. I will say, however, that my experiences with the staff, volunteers, and facilities in coastal marine and southern Californian desert protected areas over the past decade plus have been uniformly positive.

The California Department of Parks and Recreation and the Department of Fish and Wildlife have, despite some differences of opinion I have with them on a few issues, done mostly admirable work amidst a backdrop of controversy and conflicts between politically-backstopped developers intent on paving the entire state, and politically-backstopped environmental extremists who are dead set against another tree being felled or square foot of concrete being poured in California. Balancing the very different interests of native wildlife, wildlands, and resource stakeholders is a tricky and usually thankless task.

More power to both.

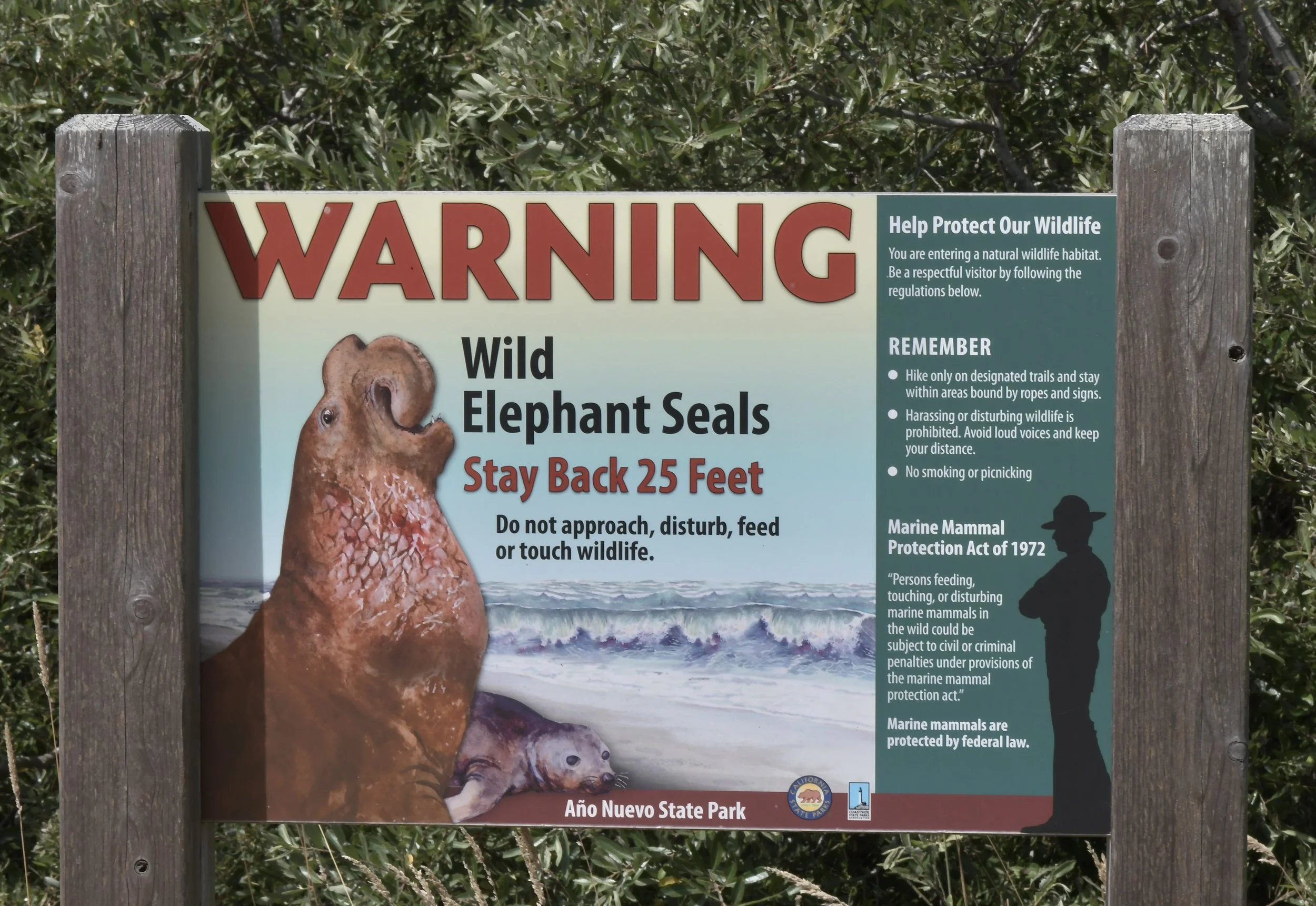

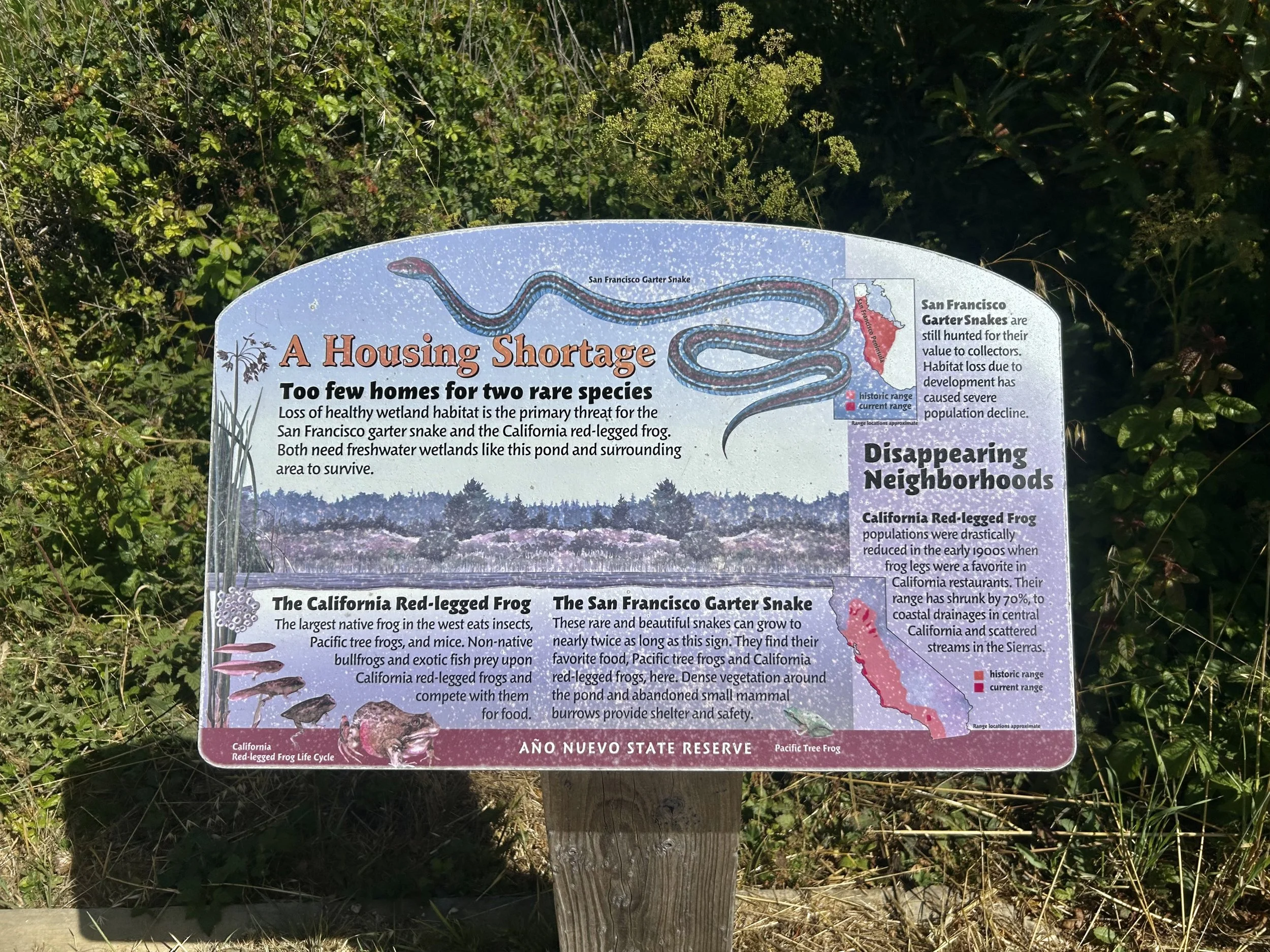

Above, signage on trails throughout the park is unobtrusive but well-designed and informative. Images: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

“Many” California sea lions, Zalophus c. californianus, and a few male elephant seals on the beach and in the surf on the eastern side of Año Nuevo Island. Blurry but illustrative image shot freehand from the mainland with a long telephoto lens. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024

A link to California State Parks’ Live Streaming Webcam on Año Nuevo Island is provided here. Use your back button to return to this article: https://www.parks.ca.gov/?page_Id=31197

Cameras are located on the southeastern end of the island and switch to three different perspectives every 30 seconds during the day (Pacific Time Zone/GMT -7:00 to -8:00). This is a clever use of technology to engage viewer interest in the wide variety of animals that visit and breed on the island.

Gallery - select species of Año Nuevo flora

Among botanists and nature photographers, coastal Californian ecosystems are world famous for the diversity of flowering plants that inhabit them, together with frequent mass blooming events that usually occur in the spring. Año Nuevo and nearby parks and natural reserves offer visitors plenty of both. Peak native plant flowering in San Mateo County is usually observed in April and May. Despite the fact that I missed mass flowering events by two months, there were still plenty of pretty things in bloom around the park during July of this year.

Yellow flowered coastal bush lupines, Lupinus arboreus, and fire engine red-flowered coast Indian paintbrushes, Castilleja a. affinus, add touches of color to the mid-summer landscape of Año Nuevo. Exposed sand dunes visible upper middle and left. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Detail of inflorescences of coastal bush lupines in late July. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Flowering hardstem bulrush or tule, Schoenoplectus acutus, growing pondside near the entrance to the park. This water feature and its marshy edge are critical resources for two endangered herptiles that occur in the park, the San Francisco garter snake, Thamnophis sirtalis tetrataenia, and California red-legged frog, Rana draytonii. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

A patch of coastal California poppies, Escholzia californica var. maritima, flowering and fruiting (note the elongated grayish-violet seed pods) in early July. Not all coastal poppies have flowers with contrasting orange centers and this form is especially attractive. The nominate orange variety is the California state flower. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Above, coast paintbrush, Castilleja a. affinus, a showy-flowered facultative hemiparasitic plant that is common and conspicuous at Año Nuevo when in flower. As true parasites, Indian paintbrush roots penetrate the subterranean vascular systems of neighboring plants – usually grasses – and extract nutrients and water from the host. Members of the genus are widely distributed across the western states south through México and Mesoamerica on into high elevation Andean cloud forest and páramo to Venezuela and Bolivia. Other Californian and upper elevation Neotropical Castilleja species are spectacular plants when in bloom. Images: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Seep monkeyflowers, Erythranthe guttata, a widely distributed low herb in the Lopseed family (Phyrymaceae) that occurs on or adjacent to wet ground. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

A beautiful group of Douglas iris (Iris douglasiana) flowering in late spring. This lovely and variably colored native species is common along the California coast. Image: ©Ron Parsons 2024.

Bluff lettuce, Dudleya farinosa, flowering at Año Nuevo in late July. While still abundant and conspicuous in many protected areas in U.S.A. California, in recent years this species has gained notoriety due to being subject to large-scale illegal collection that has decimated specific colonies in protected areas with especially attractive, high color plant forms. Poachers include both locals and foreign collectors. Unlike the closely-related lookalike genus Echeveria that occurs well to the southeast of coastal California in northern México and on into South America, many native dudleyas can be quite tricky to re-establish when removed from nature. To those so inclined, please don’t collect these plants from the wild. Image: © Jay Vannini 2024.

*Not the least of which are the vast majority of U.S. petroleum, natural gas, and strategic metal reserves.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to my good friend Ron Parsons for providing the shot of a colony of molting female northern elephant seals beached at San Simeon, San Luis Obispo County, the harbor seal group at Pescadero State Park, along with beautiful images of a group of Douglas’ irises and the very rare Yadon’s rein orchid in flower. The folks at the Pelagic Shark Research Foundation in Santa Cruz, California were extremely helpful in responding to my inquiries and putting me in contact with a researcher familiar with the history of the marked, shark-bitten seal shown above. I’m most grateful for their courtesies. Thanks also to that knowledgeable anonymous correspondent who corrected a couple misconceptions that I had on white shark-northern elephant seal interactions, providing comments on northern elephant seal thermoregulatory behaviors while on beaches, detailed information on the shark-scarred seal shown above, background information and color on the University of California’s reserves, and a handy link to the daylight live-stream from Año Nuevo Island.

References

Adachi, T., A. Takahashi, D. P. Costa, P. W. Robinson, L. A. Hückstädt, S. H. Peterson, R. R. Holder, R. S. Beltran, T. R. Keates, and Y. Nairo. 2021. Forced into an ecological corner: Round-the-clock deep foraging on small prey by elephant seals. Science Advances. May 12; 7 (20): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8115928/

Anthony, A. W. 1924. The elephant seal off the coast of Santa Cruz Island, California. Journal of Mammalogy 2: 112-113.

Bartholomew, G. A. and C. L. Hubbs. 1960. Population growth and seasonal movement of the northern elephant seal, Mirounga angustirostris. Mammalia 24: 313-324.

Beltran, R., M. A. Hindell, and C. R. McMahon. 2022. The Elephant Seal: Linking Phenotypic Variation with Behavior and Fitness in a Sexually Dimorphic Phocid. In: Ethology and Ecology of Phocids: 401-440. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359307053_The_Elephant_Seal_Linking_Phenotypic_Variation_with_Behavior_and_Fitness_in_a_Sexually_Dimorphic_Phocid

California Department of Fish and Wildlife. 2024. White Shark Information: https://wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Marine/White-Shark#542632344-are-white-sharks-endangered-in-california

Campagna, C., M. Uhart, V. Falabella, J. Campagna, V. Zavattieri, R. E. T. Vanstreels, and M. Lewis. 2023 (2024). Catastrophic mortality of southern elephant seals caused by H5N1 avian influenza. Marine Mammal Science, Volume 40 (1): 322-325. Paywalled. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/mms.13101

Curry, A. 2008. Return of the Beasts. Smithsonian Magazine online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/return-of-the-beasts-26667372/

A typical sample of of older online articles about northern elephant seals tailored to the casual reader.

Ebert, D. A. and C. Pien. 2015. Confirmation of the cookiecutter shark, Isistius brasiliensis, from the eastern North Pacific Ocean (Squaliformes: Dalatiidae). Marine Biodiversity Records 8 (e118):1-3. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280630709_Confirmation_of_the_cookiecutter_shark_Isistius_brasiliensis_from_the_eastern_North_Pacific_Ocean_Squaliformes_Dalatiidae

Hodder, J., R. Brown,and C. Cziesla. 1998. The Northern Elephant Seal in Oregon: A Pupping Range Extension and Onshore Occurrence. Marine Mammal Science, 14(4): 873-881. https://oimb.uoregon.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Mirounga-1998-MMS.pdf

Hoelzel, A.R., J. Halley, S. J. Obrien, C. Campagna, T. Arnbom, B. Le Boeuf, and G.A. Dover. 1993. Elephant seal genetic variation and the use of simulation models to investigate historical population bottlenecks. Journal of Heredity. 84 (6):443-449.

Hoelzel, A. R., G. A. Gfakas, H. Kang, F. Sarigol, B. Le Boeuf, D. P. Costa, R. S. Beltran, J. Reiter, P. W. Robinson, N. McInerney, I. Seim, S. Sun, G. Fan, and S. Li. 2024. Genomics of post-bottleneck recovery in the northern elephant seal. Nature Ecology & Evolution 8, 686-694. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/378370270_Genomics_of_post-bottleneck_recovery_in_the_northern_elephant_seal

Le Boeuf, B. J., M. Riedman, and R. S. Keyes. 1982. White Shark Predation on Pinnipeds in California Coastal Waters. Fishery Bulletin: Volume 80, No. 4, 1982. https://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/pdf-content/fish-bull/leboeuf.pdf

Le Boeuf B.J., Condit R., Morris P.A., and Reiter J. 2011. The northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris) rookery at Año Nuevo: A case study in colonization. Aquatic Mammals. 37(4): 486–501. http://ctfs.si.edu/Public/pdfs/LeBoeufEtAl.AqMamm2011.pdf

Le Boeuf, B., R. Condit, and J. Reiter. 2019. Lifetime reproductive success of northern elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris). Canadian Journal of Zoology, Volume 97 (12): 1203-1217. https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/10.1139/cjz-2019-0104

Lowry, D., A. L. Fagundes de Castro, K. Mara, L. B. Whitenack, B. Delius, G. H. Burgess, and P. Motta. 2009. Determining shark size from forensic analysis of bite damage. Mar. Biol. 156: 2483-2492. https://georgehbalazs.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/LowryEtAl2009SharkBiteForensics.pdf

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Dept. of Commerce (NOAA). 2021 (Revised 2022). Marine Mammal Stock Assessment by Species. Northern elephant seal: California Breeding. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/marine-mammal-protection/marine-mammal-stock-assessment-reports-species-stock#pinnipeds---phocids-(earless-seals-or-true-seals)

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Dept. of Commerce (NOAA). 2022. Cookie Cutter Sharks: A gallery of cookie cutter sharks and their bite wounds. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/gallery/cookie-cutter-sharks

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Dept. of Commerce (NOAA). 2024a. Laws & Policies: Marine Mammal Protection Act (1972). https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/topic/laws-policies

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Dept. of Commerce (NOAA). 2024b. Overview: Northern Elephant Seal. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/northern-elephant-seal/overview

Southall, B. L., C. Casey, M. Holt, S. Insley, and C. Reichmuth. 2019. High-amplitude vocalizations of male northern elephant seals and associated ambient noise on a breeding rookery. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 146 (6): 4514-4524. Link to abstract; full-text pdf available. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338182064_High-amplitude_vocalizations_of_male_northern_elephant_seals_and_associated_ambient_noise_on_a_breeding_rookery

Torben, R., R. L. DeLong, J. M. Erlandson, T. J. Braje., T. L. Jones, J. E. Arnold, M. R. Des Lauriers, W. R. Hildebrandt, D. J. Kennett, R. L. Vellanoweth, and T. A. Wake. 2011. Where were the northern elephant seals? Holocene archaeology and biogeography of Mirounga angustirotris. The Holocene 21 (7): 1159-1166. An excellent paper on records for Pre-contact era with archaeological evidence of northern elephant seal presence on the western coast of North America that also provides a summary of persistent commercial and scientific exploitation of the species during the early 20th century.

Uhart, M., R. E. T. Vanstreels, M. I Nelson, V. Olivera, J. Campagna, V. Zavattieri, P. Lemey, C. Campagna, V. Falabella, and A. Rimondi. 2024. Massive outbreak of Influenza A H5NI in elephant seals at Península Valdés, Argentina: increased evidence for mammal-to-mammal transmission. Preprint ms., not peer-reviewed. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.05.31.596774v1.full.pdf+ht

University of California Natural Reserve System (UCNRS). 2024. Reserves by name. https://ucnrs.org/by-name/

Weatherbee, B., C. Lowe, and C. Meyer. 2024. Activity Patterns of Tiger Sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier) at French Frigate Shoals, Northwest Hawaiian Islands. Project summary. https://web.uri.edu/wetherbee/activity-patterns-of-tiger-sharks-galeocerdo-cuvier-at-french-frigate-shoals-northwestern-hawaiian-islands/

Van Sommeran, S. 2005. Are makos really “sealeaters” (sic). Allcoast Fishing Forum. Post #68 with image. https://www.allcoast.com/threads/are-makos-really-sealeaters.4500/page-4

An interesting open discussion that (briefly) touches on white shark and elephant seal interactions during predation events along coastal California.

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC®, ©Jay Vannini 2024 and ©Ron Parsons 2024.

Follow us on: