Just Ducky!

San Francisco Bay Birding: Where All That’s Fowl Is Fair

By Jay Vannini

King Can. A feather-perfect trio of Canvasback (Aythya valisineria) contemplating a winter sunrise. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

It may surprise many non-birders to learn that some of the most attractive avian species in North America include male ducks. Globally, breeding-phase drakes in the majority of forms exhibit vivid and complex color combinations across their plumage that, in cases like Asian Baikal Teal (Sibirionetta formosa) and African Pygmy Ducks (Nettapus auritus), rival some of the showiest tropical birds. Beyond the better known native waterfowl film stars including such species as the Wood Duck (Aix sponsa), Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus), and King Eider (Somateria spectabilis), breeding drakes of many other indigenous duck taxa display what can certainly be described as flamboyant appearances.

Breeding ducks are among the most sexually dichromatic of all bird groups, and many show extreme variances in plumage colors between males and females that are comparable to other well-known avian families that exhibit sexual dichromatism such as pheasants (Phasianidae), birds-of-paradise (Paradisaeidae), and tanagers (Thraupidae). Curiously none of the larger geese and swans, which are members of same family as ducks (Anatidae), exhibit notable differences in plumage color between the sexes.

That is not to say that all male ducks are colorful or are conspicuously sexually dichromatic. Apart from males in eclipse (=non-breeding) plumage, several well-known North American ducks are somberly colored and show only minor–or no–color differences in feather colors between drakes and hens year-round, e.g., Black Ducks (Anas rubripes), Mottled Ducks (A. fulvigula), Black-bellied Whistling Ducks (Dendrocygna autumnalis), and Fulvous Whistling Ducks (D. bicolor). Drakes of other species are perhaps better described as “handsome” rather than “beautiful”, including well-known larger game species such as Canvasbacks (Aythya valisineria), Pintails (Anas acuta), and Gadwalls (Mareca strepera).

Stocky & handsome is always good, but trim & sexy is even better. A quartet of plugged-in and lit-up native drake ducks in their courtin’ threads is shown below.

A chilled-out drake Hooded Merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus) in breeding colors resting on Oracle Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. The riotous male courtship displays of this beautiful North American diving duck are some of the most spectacular reproductive behaviors in the entire family. For those interested, there are many excellent videos showing these wild rave-ups posted online. Trust me - they are worth a look! When the males’ crest is fanned upright during courtship or territorial encounters with rivals, the vivid white patch flares massively and seems to dominate the scenery. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Breeding drake Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus), a rare vagrant to this area that is wintering further south than is typical for the species. Two subspecies of Harlequins are known as breeding birds from the northern parts of coastal ranges of both coasts of North America, eastern Eurasia, Greenland, and Iceland. A beautiful freshwater diving duck that is usually associated with rushing mountain streams on its breeding grounds and alongside rocky coastal bay and ocean shores on migration. Coyote Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Drake Cinnamon Teal (Spatula cyanoptera) looking slightly ruffled after I rousted him from a morning nap. Breeding males are considered by many to be among the most attractive dabbling duck in the Americas. Cinnamon Teal have localized nesting populations in the American West as well as on Andean lakes and across Patagonia in South America. Most USA-origin birds migrate in winter to western México and Central America where they often mix with tropical waders. Radio Road, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

American Green-winged Teal (Anas carolinensis). Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Ducks in the San Francisco Bay Area

North American waterfowl are the most intensely studied, extensively sampled, and carefully monitored group of wildlife anywhere. Because of a convergence of interests by state, federal, and private groups, duck and geese numbers are systematically and more or less accurately censused every year on their breeding grounds and migration routes from Alaska and northern Canada to southern México. Preliminary numbers from 2024 indicate that USA breeding waterfowl populations of surveyed forms (19 species, 34 million individuals) showed their first year over year increase since 2015 and are at their highest levels overall since the 2005 count (USFWS, 2024; Ducks Unlimited, 2024). Given that this print occurred concurrently with the highly pathogenic avian influenza pandemic (see below), these numbers are welcome news indeed.

In contrast with the national survey, the numbers of breeding ducks in California declined substantially–25%–between 2023 and 2024 censuses and remains 30% below long-term average numbers. This despite near long-term average snow- and rainfall during the 2024 water year). Reductions in breeding duck numbers are attributed to loss of critical nesting habitat, especially in California’s Central Valley (Brady & Weaver, 2024), although other factors may also be in play. Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) declines comprised much of these losses.

Waterfowl are abundant and conspicuous members of San Francisco Bay Area avifauna. Situated near the center of the Pacific Flyway that stretches from Alaska to Chile, it includes several important hot-spots for migrating waterfowl. Its relative proximity to the state’s Central Valley whose wetlands, while now much reduced from their former extensions, are still critically important habitat and are a very productive region for aquatic birds in general. At just over 1,700 sq. mi/4,440 sq. km, the SF Bay and Delta is second largest estuary on the Pacific Coast of the Americas and certainly the most densely-urbanized one on its margins. The Sacramento River Valley, the SF Bay proper, and rocky Pacific coast shorelines close by continue to attract huge numbers of migrating waterfowl annually (Ducks Unlimited, 2024; pers. obs.). The importance to migrating waterfowl of Central Valley native wetlands in both private and public hands, together with flooded rice fields, is evidenced by California’s Merced County producing a larger annual duck harvest for hunters than any other county in the USA (Otteson, 2024).

Birdwatching is a very popular activity in the area where I live in coastal central California. During early morning or late afternoon walks through any of our local parks and nature reserves one will invariably cross paths with people dressed as if bound for equatorial Africa with a pair of binoculars and/or a telephoto-equipped DSLR camera hanging around their neck. A revision of Cornell’s Laboratory of Ornithology online resource eBird for San Mateo County shows numerous local birding hot-spots along the South Bay with lists and photographic records–some of superb quality–that are constantly updated by area birders (eBird, 2021; 2025). Online birding fora and chats seem heavily trafficked by locals, and the bird reporting websites such as eBird’s Rare Bird Alert are handy tools for area birders looking to pad their life lists with vagrants from Eurasia or the High Arctic.

From a conservation standpoint the SF Bay includes three National Wildlife Refuges managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service and 10 Wildlife Areas and Ecological Reserves managed by California Department of Fish and Wildlife, some of which permit seasonal bird hunting. The San Francisco Bay Bird Observatory and other nonprofit conservation organizations are active in habitat restoration efforts.

Early winter morning view of Bair Island looking across the wetland towards Redwood Shores and the San Francisco Bay. The Bayshore Freeway-US Route 101 is ~200 yds/m behind this spot, and at times you can readily identify certain duck and geese species floating on the slough directly adjacent to the concrete safety barriers while driving in the right lane past this reserve. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Duck hunting is also a widespread and popular past-time throughout North America, including in the state of California. Both guided and individual shotgunners hunt in this area during the winter season. Federal duck stamps, together with hunting and fishing licenses, are a major source of funding for critical habitat acquisition and state wildlife conservation programs in the USA. It is worth noting that there is concern that a reduction in gun hunters in this country in the future will reduce budgets for conservation programs in some states. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife posts a daily schedule for bird hunting in northern California that begins on September 01 and ends on January 25, including bag limits and permitted times of the day.

The Species

The SF Bay Area duck list includes 33 species from 15 currently accepted genera confirmed to date. Most are long distance migrants, with several considered rare to extremely rare vagrants. Species highlighted in bold were photographed by me over a one month period spanning the first week of January to the first week of February 2025. Images of these species are included in the Gallery section at the end of the article.

American Wigeon (Mareca americana) “dabbling” along a rocky shoreline on the western edge of the San Francisco Bay. The white-cheeked drake shown middle right is the rare color phase commonly known as a Storm Wigeon. Seal Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Dabbling & Perching Ducks

Northern Pintail (Anas acuta)

Green-winged Teal (Anas carolinensis)

Eurasian Green-winged Teal (Anas crecca)

Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos)

Redhead (Aythya americana)

Lesser Scaup (Aythya affinis)

Ring-necked Duck (Aythya collaris)

Tufted Duck (Aythya fuligula)

Greater Scaup (Aythya marila)

Canvasback (Aythya valisineria)

American Wigeon (Mareca americana)

Falcated Duck* (Mareca falcata)

Eurasian Wigeon** (Mareca penelope)

Gadwall (Mareca strepera)

Northern Shoveler (Spatula clypeata)

Cinnamon Teal (Spatula cyanoptera)

Blue-winged Teal (Spatula discors)

Ruddy Duck (Oxyura jamaicensis)

Wood Duck (Aix sponsa)

Fulvous Whistling Ducks (Dendrocygna bicolor)

Drakes of all the Bucephala forms in a rare interspecific courtship display involving this trio of diving duck species with females waiting stage right. Clockwise from top, Common Goldeneye (B. clangula), Barrow’s Goldeneye (B. islandica), and Bufflehead (B. albeola). Smith Slough, Bair Island, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Diving Ducks & Seaducks

Bufflehead (Bucephala albeola)

Common Goldeneye (Bucephala clangula)

Barrow’s Goldeneye (Bucephala islandica)

Hooded Merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus)

Common Merganser (Mergus merganser)

Red-breasted Merganser (Mergus serrator)

White-winged Scoter (Melanitta fusca)

Black Scoter (Melanitta nigra)

Surf Scoter (Melanitta perspicillata)

Smew**** (Mergellus albellus)

Long-tailed Duck (Clangula hyemallis)

Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus)

King Eider (Somateria spectabilis)

Notes

Several interspecific and intergeneric duck hybrids have also been reported from and photographed in the SF Bay Area.

*Falcated Duck reports from the Bay Area are historical and date from the last century. There are contemporary (2010s) reports from elsewhere in northern California so experienced local birders coming across any unfamiliar ducks after severe weather events should certainly examine them closely.

**Eurasian Wigeon are now confirmed to be a breeding species in North America in the Alaskan Aleutians (Withrow, 2022). They are regularly reported from the Pacific Northwest and central California as vagrants, usually mixed in large flocks of American Wigeon. Birds observed in the SF Bay Area–with increasing frequency it seems–are of unknown origin (see image below). Natural hybrids with American Wigeon are being photographed in the Pacific Northwest and elsewhere on a regular basis, suggesting that they may be breeding at locations further south than northwestern Alaska.

***Fulvous Whistling Ducks were formerly common breeding birds in the Central Valley and occasionally in the SF Bay Area in the late 19th century. Due to habitat loss and conflicts with agricultural interests they are now largely extirpated as breeding birds in USA California.

****Individual vagrant Smew are very rarely reported in this area.

“You can observe a lot just by watching.”

Drake Buffleheads (Bucephala albeola) displaying on the Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Ducking around the neighborhood

During a recent spell of unusually fine winter weather that coincided with the conspicuous presence of large numbers of migrant waterfowl very near my home, as a lark I decided to see just how many of the duck species reported from my area I could photograph in a month.

This article was hatched from that personal challenge.

The rule I set for myself was that the point count was to be restricted to within a 3.0 mi/4.8 km radius of my residence, but most were actually shot within a mile/1.3 km of my front door. The date range ran from January 08 through February 07, 2025. When the mood struck me and the weather cooperated I tried to get out for a couple hours a day at least four days every week, but it was by no means any sort of forced march to every corner of this part of the bay to try and check off the entire list of possibles. All the observations were made from land on public access.

Beggars can’t be choosers, so some of the images I include here reflect struggles with problem early morning/late afternoon light conditions or with uncooperative avian models who would not permit close approaches. Still, I think it provides a pretty good idea of just how diverse the area’s duck fauna is.

Belmont Slough looking east at Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Pickleweed (Salicornia pacifica) mats in the foreground. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

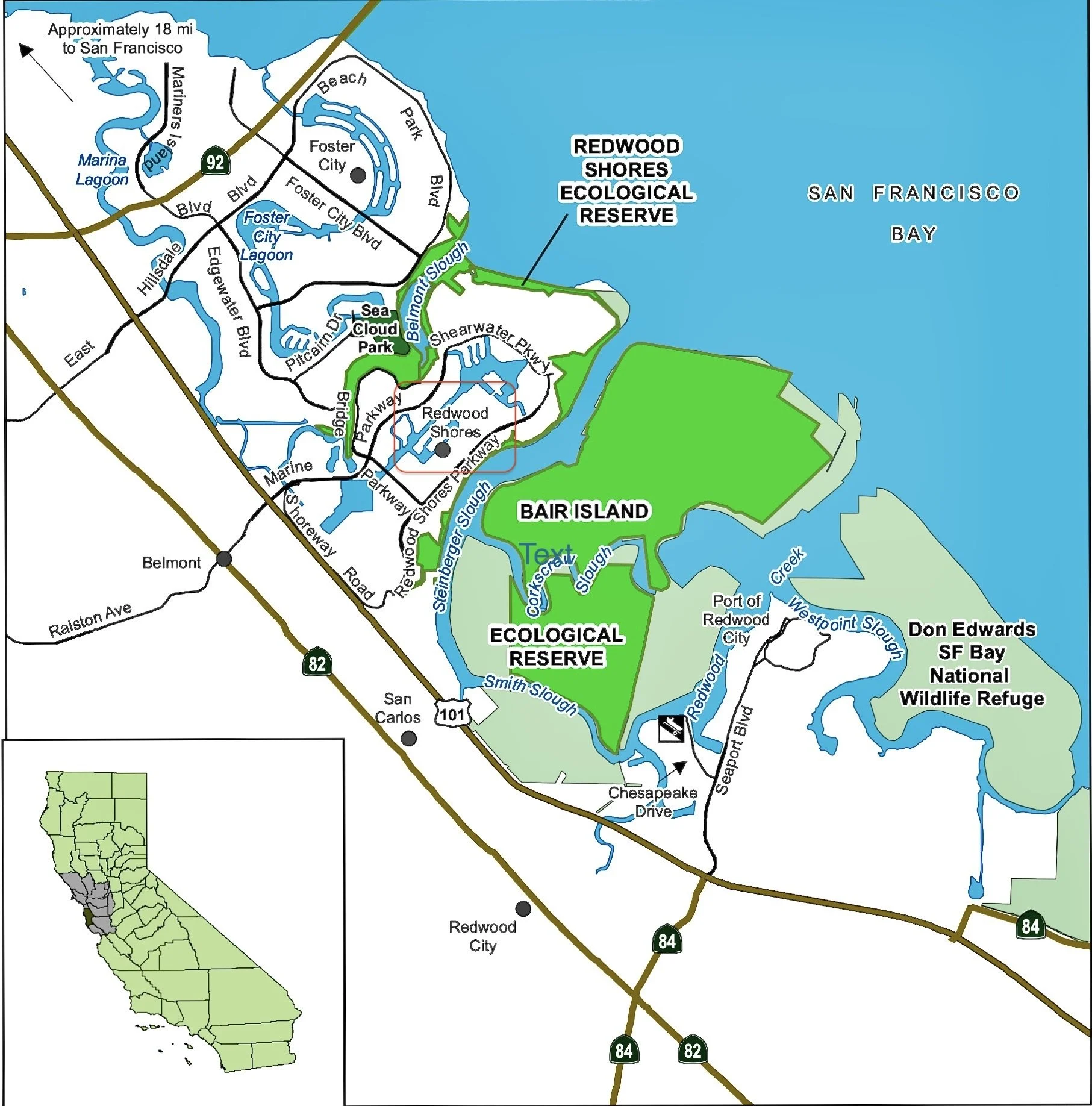

A map of my area with many of the localities mentioned in the text shown, and my immediate neighborhood in Redwood Shores shown boxed in red. Heavily edited from a map provided online by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Selecting from a menu of shoreline and marsh habitats around me and over the hills towards the Pacific, I decided to stick to sites I was already familiar with in and immediately adjacent to Redwood Shores. The included the Oracle Pond-Belmont Slough, Bird Island-Redwood Shores Ecological Reserve, Bair Island-Don Edwards SF Bay National Wildlife Refuge, the Nob Hill Pond and adjacent Steinberger Slough-Bair Island Ecological Reserve, and the Radio Road-Gossamer Avenue Pond area. In addition I added a few shots taken up the coast a few more miles at Seal Point and Coyote Point as well as over the hills to the west of me on the Pacific coast at nearby Pillar Point Harbor and Mori Point. These trips out of the immediate vicinity of my home were to look for a couple species that I had observed but had been unable to photograph nearer to home.

The results of this casual survey–21 duck species including many thousands of individuals–proved pleasantly surprising. It confirmed a prior conclusion I had arrived at that my immediate neighborhood, despite being heavily developed and having a large concrete footprint comprised of the Bayshore Freeway, high tech and biotech campuses, retail outlets, as well as single family homes and condominiums, encompasses some first class waterfowl habitat. This, not to mention outstanding areas to view large flocks of shorebirds, waders, seabirds, and associated raptors such as Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus), Cooper’s Hawks (Astur cooperii), and Great Horned Owls (Bubo virginianus) breeding in suburban settings that border local wildlife preserves.

The Nob Hill Pond at Redwood Shores. This image was taken at high tide in the early morning when birds are mostly absent. This suburban drainage pond, which lies immediately adjacent to the Steinberger Slough and the western edge of the San Francisco Bay is a local birding hot-spot. Despite its relatively small size (~220 yds/m x ~100 yds/m), this pond is one of the most productive sites in the SF Bay Area to view migrant waterfowl. Thirty-four duck species and hybrids, together with a half dozen geese and swans, have been confirmed from this site over the past few years. During mid-winter late afternoons as many as ~2,000 ducks of various species–but most notably Canvasbacks–may be counted sleeping on the pond. Its shallow freshwater surface layers after storms and close proximity to the relatively inaccessible interior of the Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge likely explains its attraction to migrant waterfowl, formidable diversity and bird numbers. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

A flock of American Avocets (Recurvirostra americana) wheeling over a flooded meadow on the northern edge of the Belmont Slough with apartment blocks in Foster City visible in the background. The proximity of wetland edge to urban development in some reserve areas near me is evident in this image. San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Bird Island at low tide. The south San Francisco Bay, Hayward-San Mateo Bridge, and the East Bay viewed from north Redwood Shores. This restored salt marsh is dominated by Salt Grass (Distichlis spicata), California Cord Grass (Sporolobus foliosus), and Pickleweed lies on the southern edge of the Redwood Shores State Marine Park. It is an important staging ground for migrating birds and also provides important nesting habitat for Ridgway’s Rails (Rallus obsoletus) and Short-eared Owls (Asio flammeus). San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

The most commonly observed duck species during my point counts were (in descending order of abundance), Canvasbacks, Northern Shovelers, both scaup species, Buffleheads, and American Wigeon. Because most flooded areas in my neighborhood are saltwater, duck species that prefer freshwater habitats and that are common elsewhere, such as Wood Ducks, Ring-necked Ducks, and Redheads are rare visitors that I was unable to find during this casual survey. Likely because of this fact, freshwater lenses that form on the surfaces of saltwater ponds following heavy rains seem to attract duck species that are otherwise uncommon in the area.

Other than extensive marine and brackish shorelines, this part of the South Bay is crisscrossed with lagoons, sloughs, and reservoirs, together with salt marshes, rocky bay edges, and tidal mudflats. Many residential developments in the area incorporate extensive brackish water features in their artificial landscapes that are used by waders, shorebirds, and waterfowl. Extensive habitat restoration has occurred in and near Redwood Shores over the past three decades that greatly improved the quality and productivity of local wetlands.

Finally, for background: I have studied wild and captive birds around the world since early childhood. Aside from practicing falconry and developing captive breeding and reintroduction protocols for endangered tropical birds, I have also worked with, and published on, the ecology and conservation of long distance avian migrants in Guatemala (e.g., Vannini, 1994). I also have experience conducting multi-year inventories of migrating Nearctic passerines and waterfowl at a RAMSAR site in northern Central America under grants from both the World Wildlife Fund-U.S. and the National Fish & Wildlife Foundation.

That said, I suppose I am best considered an accidental birdwatcher at best and steer wide of life-listing fanatics as lampooned in the 2011 comedy film, “The Big Year”. Still, having observed wild birds–including many considered rara avis–across Europe and the Americas, southern Africa, Japan, and Papua New Guinea, I have a fairly high bar when it comes to being impressed by a birding spot. Last month I was surprised to find there is one that I have neglected to visit for more than decade located just a twenty minute stroll from my front door where over 30 species and four natural hybrids of ducks, geese, and swans have been reported during the past three years.

The San Francisco Bay and the Hayward-San Mateo Bridge on a still morning viewed from Seal Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Tricks of the Trade

Because many duck species are relatively large and attractive, sometimes permit close approaches on foot, and can be common to abundant even in seemingly marginal wetland relics and drainage ponds, they are excellent subjects for study by beginning birdwatchers, photographers learning how to photograph wild birds, or other general fans of natural history. The skills obtained during the practice of stalking migrant waterfowl to within distances that permit close observation and photography are directly applicable to other bird groups.

Getting close to often skittish ducks for purposes of photography or close observation requires a bit of prior strategizing. Beyond the standard dawn and dusk preferred times for bird-watching that apply almost anywhere, seasonality, weather, and tidal cycles play a huge role in determining success. Since I use a fairly long telephoto lens for photography, excellent light is a must for my days out. Brilliant winter mornings or afternoons and quality glass are key to capturing crisp and colorful images of waterfowl when they are out at any distance and one is using manual focus. Generally speaking, I find that periods around high tide coupled with either sunny early mornings or mid– to late afternoons produce the best combination of conditions to see migrant ducks up close since the water’s edge where many will be feeding is closer to solid ground during those periods.

For a variety of reasons it pays to check out productive sites every day or so when migrating waterfowl traffic is high. Besides duck populations that stage for months at a given locality while on migration, some species’ numbers “pulse” over time as they move through a locality and may be abundant on a given day only to be completely absent the next. Vagrants generally accompany flocks of other duck species, so keep an eye out for obvious oddities among any aggregations of waterfowl.

Peak low tide cycles in the late afternoon in this area will often concentrate ducks and other aquatic birds in the various storm drainage ponds that are scattered about. Snoozing ducks will often permit very close approaches but generally produce rather boring photos of seemingly headless birds. Action shots of ducks coming off the water or in flight are almost always preferred to images sitting on the water, unless you want to emphasize the birds’ key characters for ID purposes (like here). Excellent light, fast shutter speeds, continuous shooting mode, good optics, and better eyesight are all invaluable ingredients to getting perfectly focused shots of tricky maneuvers made while birds are flying.

Note that migrating waterfowl staging in or adjacent to areas where hunting is permitted can be extremely wary of humans carrying any elongated and dark-colored items in their hands. Spotting scopes, monopods and tripods, trekking poles, as well as long telephoto lenses all presumably look like long guns to them. Some will rocket off the water when approached if any of these items is detected that might otherwise stay in place if you were just carrying binoculars. While as a general rule I do use neutral-colored clothing when birdwatching, I don’t bother with funny hats sporting woodland patterns nor do I employ camo tape or Neoprene sleeves on my photographic gear. However they are definitely something worth evaluating especially if you are using a vehicle, a duck- or a tree blind for cover to get up close and personal for especially shy species.

There are several articles on this website by Peter Rockstroh that provide valuable tips for photographing wild birds, including advanced flash photography, all listed in the menu under “Neotropical Nature” in the “Colombian & Peruvian” section. Waterfowl photography is a highly competitive subset of bird photography that is populated by many near-obsessed and extremely talented professional and amateurs around the world, some of whom maintain blogs dedicated to showcasing their portfolios. Then there are the duck hunters, waterfowl ecologists, and wetland managers who are also very competent photographers, and they add to the immense corpus of excellent images of ducks, geese, and swans posted online. Any time I (briefly) feel cocky about the quality of a bird photo I just took, a glance at the better images of that same species posted on the internet will inevitably leave me feeling like putting away my camera and taking up golf.

Dark Angel. The back of a distant drake Surf Scoter (Melanitta perspicillata) lifting off a mirror-flat San Francisco Bay at Coyote Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Migrating Ducks and Avian Influenza

Since this topic is very much in the news of late…

Counterintuitively, the increase in breeding waterfowl populations across most of the USA during 2024 reported by the USFWS coincided with a marked uptick in cases of the Eurasian-origin highly pathogenic avian influenza virus or bird flu (HPAIV subtype A/H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b, better known as H5N1) detected in both wild birds and domestic fowl across the country. The wild bird-adapted strain was first identified in native avifauna and poultry in North America (NE Canada) in December 2021 and promptly caused losses in commercial poultry flocks in the USA early the next year (Caliendo et al., 2022; CDC, 2024). Migrating wildfowl have long been known to be both vectors and sentinel host species of avian influenza, although susceptibility and mortality rates varies widely between species and some taxa show apparent resistance to the disease (Keawcharoen et al., 2008). For whatever reason, in the USA, migrant waterfowl and poultry farms located along the northern sections of Central and Mississippi Flyways seem to be especially hard hit by H5N1.

Many duck and geese populations winter in suburban environments and even urban parks across all four migration flyways in North America. Migrating birds of all types and their waste products frequently come into contact with humans and domestic animals. While still considered a minor threat to most native birds, the current strain of avian influenza has proved deadly for some seabird, shorebird, and seal populations in Eurasia, North and South America (Campagna et al., 2023; Haman et al., 2024; Yates, 2025), not to mention farmed poultry in the USA and elsewhere. Despite its seasonality and reportedly low risk to humans (NIH, 2024) H5N1-associated economic losses in the corporate poultry industry–that are largely subsidized by taxpayer-funded compensation (USDA, 2024)–have been both significant and market distorting, as anyone who has purchased eggs recently is well aware.

Given the concern that public and animal health institutions have expressed about bird-to-mammal transmissions of H5N1 special scrutiny is now the order of the day for visibly sick or dead wild birds encountered in urban and suburban areas (CDC, 2025; Yates, 2025). Worst case scenario fear porn offerings by the commercial media aside (e.g., Bourke, 2024), common sense dictates that one should not handle dead or ailing birds of any type found in your garden or while out and about. Both avian botulism (Clostridium botulinum) and avian cholera (Pasteurella multiocida) can also occasionally produce massive die-offs in ducks and other waterfowl as well as seabirds, so one should not automatically assume that a few dead ducks or geese at a local pond = H5N1 and freak out.

Where possible, also try to prevent domestic cats from eating wild birds–for other obvious reasons as well–since avian-to-feline transmission of avian flu is now a well-documented risk to these creatures.

Gallery

The gentleman in a herringbone suit. Drake Northern Pintails (Anas acuta) invariably appear in immaculate feather and are popular with birders and duck hunters alike. Together with Northern Shovelers (Spatula clypeata), these abundant ducks have the widest distributions of any waterfowl species. Both breed across the northern hemisphere and winter as far south as South America, central Africa, and across south Asia. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

A pair of migrant Northern Pintails. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, Californiia. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Mixed flock of Northern Pintails, American Wigeon, and Canvasbacks. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Green-winged Teal (Anas carolinensis). This is the smallest dabbling duck in North America and a common to periodically abundant local migrant. Green-wings are the most popular duck among hunters in the state, and the annual harvest is consistently the highest among all waterfowl species here. Bay Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Five drake Green-winged Teal displaying to a single hen. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Drake Green-winged Teal showing its crest. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

A wary pair of Mallards in a Pickleweed stand. Bay Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Apart from migrants, Mallards also breed in this area. Reflecting statewide censuses in 2024, we also saw noticeably lower than usual numbers of Mallards this winter. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

A domestic duck x Mallard hybrid hanging out with a flock of wild Mallards. This type of hybrid is commonly observed in the company of native Mallards. The amount of white and body feather coloration varies between individuals. Mallards worldwide also hybridize with other duck species. Seal Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

A wild drake mallard traveling with a mystery melanistic hybrid. The plumage color and black bill on the smaller hybrid suggests an interesting genetic source. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Mallard breeding aggregation. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Lesser Scaup (Aythya affinus). These common diving ducks are better known to hunters as Bluebills. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Flock of Lesser Scaup at the Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Lesser Scaup drake with a pair of hens. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Lesser Scaup. Preserve Park, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Drake Tufted Duck (Aythya fuligula). This beautiful Eurasian duck is a regular vagrant to both coasts of the USA and reports posted online show that both sexes show up in bodies of water in Redwood Shores more or less every other year. This one arrived in early February 2025 and proved a magnet for local birders. Oracle Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Tufted Ducks often travel as single birds or pair with other pochards or scaup. This handsome devil was embedded in a large mixed flock of Greater and Lesser Scaup that spent the winter just down the street from me at the Oracle Pond. They have also been sited on several occasions from the Nob Hill Pond, also in my immediate neighborhood. Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Tufted Duck drake flocking with a group of drake Greater Scaup. Oracle Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Greater Scaup (Aythya marila) and Lesser Scaup (A. affinus) Oracle Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Drake Greater Scaup on the Gossamer Avenue pond. Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Greater Scaup. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Mixed flock of Greater and Lesser Scaup drakes together with a pair of Common Goldeneye (Bucephala clangula). Huge rafts of thousands of mixed Scaup and Common Goldeneye were observed gathered near shore on the west side of the San Francisco Bay alongside the Bayshore/101 Freeway adjacent to the Brisbane Lagoon in late March 2025. This mass flocking event was brief, and two days later the birds had vanished. Oracle Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Drake Greater Scaup. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Comparison of Greater (left) and and Lesser (right) Scaup hens. Oracle Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Comparison of Lesser (left) and Greater (right) Scaup drakes. Oracle Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Canvasbacks: Widely known as the King of Ducks (nicknamed “King Can”) this large, handsome, and fast-flying duck was the target of calamitous levels of market hunting in the Chesapeake Bay and elsewhere in the eastern USA during the 19th century. Mark Twain held it in very high esteem as table fare and east coast punt gunners brought this species perilously near to extinction by the early 1900s. Canvasbacks were one of the major beneficiaries of passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act by Congress in 1918, which may very well have saved the species from extirpation on the Atlantic Flyway. Despite its penchant for big water while on migration, Canvasbacks favor prairie potholes during the breeding season. Their nests are frequently parasitized by the closely-related Redhead (Aythya americana), with as many as 80% of nests parasitized in some areas of Canada (Sugden, 1980; Sorensen, 1997).

Despite cyclical and sometimes marked declines across parts of their range, Canvasbacks are the most abundant migrant duck species in my area every year. Good numbers of them are always evident at all the spots I visit, with high numbers often visible sleeping on the surface on Nob Hill Pond in the late afternoons from December through February. At coastal outlooks such as Shell Beach, Seal Point, and Coyote Point Canvasbacks are always almost visible resting offshore in the morning. They are the premier game bird in my area and are eagerly sought by sport hunters despite low permitted bag limits.

Portrait of a drake Canvasback in breeding plumage. Seal Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Canvasbacks. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Sleeping canvasbacks. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Early morning Canvasback arrivals. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Partial perspective of a large Canvasback raft gathering on the Belmont Slough that includes males in both breeding and eclipse plumage. Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Canvasbacks landing. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Portrait of a drake American Wigeon (Mareca americana) in breeding color. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Another drake American Wigeon in breeding plumage still molting into the bright green post-ocular stripe. Head coloration on drake winter American Wigeon is variable in this area and can lead to confusion with Eurasian Wigeon hybrids shown below. Coyote Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

A richly-colored hen American Wigeon. The characteristic dark eye shadow and grayish head readily separates it from hen Eurasian Wigeon (Mareca penelope), also seen in this area as vagrants. A trio of more typically colored females is shown below. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Partially leucistic drake American Wigeon in breeding plumage with unusual coloring on its head and secondary covert feathers, shown together with a typical hen. Showy but aberrant “high-white” drakes of this species with pure ivory-colored cheek and neck feathers are known by hunters and birders in the USA as Storm Wigeon or White-cheeked Wigeon. They are rare but regularly occurring mutations that are occasionally observed and photographed across the continent wherever large flocks of American Wigeon congregate on migration. One is shown in the image at the beginning of this article feeding with a flock of normally-colored birds at nearby Seal Point. While not a “storm” phase, the head and neck of this fellow are noticeably different in appearance from a run-of-the-mill drake American Wigeon as shown above and below. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

American Wigeon flock offshore in the SF Bay at Coyote Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Natural hybrid Eurasian x American Wigeon drake (Mareca penelope x M. americana) in breeding color. These hybrids are only slightly less common than Eurasian Wigeon as vagrants in this area. The hybrid drakes can be quite variable in color, with degrees of influence evident in individual birds from both the parent species. Coyote Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Another hybrid Eurasian x American Wigeon drake. In my experience these birds invariably flock with American Wigeon and can sometimes be hard to differentiate in poor light. There is no doubt that hens also occur here, but the similarity in appearances of these two wigeon species makes it challenging to identify them in the field. Hen wigeon that lack the dark eye smudge characteristic of American Wigeon females should be glassed closely to determine whether they are either Eurasian (rusty heads) or hybrids (grayish heads).

Drake Gadwall or Gray Duck (Mareca strepera) in breeding plumage. Gadwalls are year-round residents in this area but are infrequently observed despite breeding in the state. California Fish and Wildlife’s 2024 census of breeding waterfowl showed that Gadwall numbers in the state had suffered a 39% year-over year decline and were a whopping 96% below long term average numbers. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Trio of Gadwalls. Drake Gadwalls in eclipse plumage resemble hens but retain their black bills. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Sleeping Gadwalls. Preserve Park, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Displaying drake Gadwall in breeding plumage in the foreground with two pair behind. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Three Gadwall drakes chasing a hen. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Drake Northern Shoveler (Spatula clypeata). Northern Shovelers are the second most common migrant duck species in this area, and often the most conspicuous one on a given body of water. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Northern Shovelers. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Northern Shovelers on Bair Island, Redwood City, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Shovelers feeding in shallow water. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Drake Northern Shoveler with his colorful landing gear coming down as he parachutes in on the Belmont Slough. Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California.

Drake Cinnamon Teal (Spatula cyanoptera) portrait, with pin feathers emerging on its face as it terminates the molt from eclipse into breeding plumage. Cinnamon Teal are far more familiar to birders and waterfowl hunters in the American West than elsewhere in the country, where they tend to be rare stragglers. The are also regulars in winter across western México and into Guatemala, then occasionally as vagrants as far south as Costa Rica and Panamá. Radio Road, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Cinnamon Teal pair. Radio Road, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Cinnamon Teal drakes. This species is another year-round resident that is seen on an infrequent basis when northern migrants dominate the scene. Cinnamon Teal have the widest resident distribution of any duck species in the Americas, with five subspecies that occur discontinuously from southwestern Canada to southern Chile and Argentina. The northern South American races are mostly restricted to high elevation Andean wetlands but do effect local migrations. Gossamer Avenue Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Cinnamon Teal pair lit by late afternoon sunshine. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Another brace of drake Cinnamon Teal finishing up their molt into full breeding plumage. Most males are in full color in this area by mid-March. Outside of the breeding season when in eclipse plumage, mature males are far less colorful than those shown here. Radio Road, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Cinnamon Teal in breeding plumage. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Drake Cinnamon Teal in full breeding attire displaying a blue wing patch or speculum on its secondary covert feathers that gives this duck its Latin specific epithet, cyanoptera = blue-black feathers. Radio Road, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Drake Blue-winged Teal (Spatula discors). Preserve Park, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Blue-winged Teal pair. Blue-wings can be relatively abundant in this area for brief periods while coming and going to their preferred wintering grounds in Latin America. Huge rafts of migrant Blue-winged Teal may be observed in protected wetlands from western México well into northern South America during fall and winter. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Blue-winged Teal on a mud flat. Steinberger Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Blue-winged Teal. Radio Road, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Resting Blue-winged Teal. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Blue-winged and Cinnamon Teal in breeding plumage. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Drake Ruddy Duck (Oxyura jamaicensis) in breeding plumage. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Ruddy Duck, non-breeding drake in mid-winter eclipse plumage. Notice the change in bill color evident in the drake shown in the prior image. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Hen Ruddy Duck. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Ruddies often run across the water while flapping their wings rather than take flight when traveling short distances. Belmont Slough, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

A small flock of Ruddy Ducks (Oxyura jamaicensis). Another abundant local resident duck. Breeding males are colorful but both sexes are otherwise drab-looking for much of the year. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Bufflehead (Bucephala albeola) drake. Buffleheads are common and conspicuous throughout this area, and are one of the most abundant migrant duck species during mid-winter. Breeding in boreal forest from north-central Canada to central Alaska, they winter the lengths of both coasts to as far south as central México. Seal Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Immature hen Bufflehead. Coyote Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Bufflehead chase. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Bufflehead pair. Radio Road, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Bufflehead drake with a trio of hens he is courting. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Bufflehead flock assembled for courtship rituals. Bufflehead pre-nuptials involve lots of head-bobbing, wing-flapping, chest-bumping, mock combat, and occasional nipping. These displays intensify through the later winter and by the beginning of spring can involve dozens of birds of both sexes harmlessly crashing into one another in mosh pit encounters that can last for up to five minutes. Short display flights back and forth across the display area, mostly by drakes, make for interesting spectacle. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

More of the same. A pair of drakes in display. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Goldeneyes: The bright yellow irises on these handsome ducks make them especially appealing to birders, decoy carvers, and ornamental waterfowl collectors. Despite reputedly being the worst-tasting ducks, goldeneyes are popular targets for hunters across their ranges. Outside of areas where they are hunted, they are often fairly bold and permit close approaches when backed by plenty of open water. Like Buffleheads and Barrow’s Goldeneyes, they are boreal forest cavity nesters in trees or snags, often recycling woodpecker nest-holes in conifer and aspen woodlands. In common with most of the duck species shown in this article, goldeneyes breed in shallow freshwater habitats but winter to estuaries or saltwater ecosystems.

Drake Common Goldeneye (Bucephala clangula). The most widespread of the three species in this genus, Common Goldeneyes occur throughout North America and Eurasia. Smith Slough, Bair Island, Redwood City, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Hen Common Goldeneye. Smith Slough, Redwood City, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Common Goldeneye trio. Immature females lack the orange lipstick visible here and have uniformly dark bills. Smith Slough, Bair island, Redwood City, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Immature drake Common Goldeneye. Young Common Goldeneyes of both sexes differ substantially in appearance from adults. Oracle Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Common Goldeneye lineup. Smith Slough, Bair Island, Redwood City, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Formal attire on a duck? A drake Common Goldeneye seemingly sporting an elegant tux in early morning shadow. Oracle Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Barrow’s Goldeneye (Bucephala islandica) drake at Smith Slough, Bair Island, San Mateo County, California. Barrow’s Goldeneye occur on a regular basis in this area during winter but are greatly outnumbered by Common Goldeneyes, with which they usually mix. The crescent shaped facial patch that extends to well above eye level readily distinguishes them from Common Goldeneye. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Barrow’s Goldeneye pair. Drakes are among the most elegant looking North American duck species. Smith Slough, Bair Island, Redwood City, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Barrow’s Goldeneye courtship display. Like Buffleheads, Barrow’s Goldeneyes are exclusively North American breeding birds. Smith Slough, Bair Island, Redwood City, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Drake Barrow’s Goldeneye. Oracle Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Portrait of a breeding drake Hooded Merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus). Oracle Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Hooded Mergansers can be abundant breeding birds in some parts of the Upper Midwest and Pacific Northwest USA–sometimes nesting in big city parks and backyard ponds in rural areas–but are mostly uncommon and noteworthy winter visitors to the SF Bay Area. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Drake Hooded Merganser showing partially elevated crest. In full nuptial display this brilliant white patch fans forward to extend well over the eyes. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Hen Hooded Merganser looking more than a bit saurian with her elongated, hooked, and serrated bill. Oracle Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Sleeping Hoodies. One of my personal favorites among the world’s waterfowl. Oracle Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Hooded Merganser flock floodlit in early morning sunshine. Hoodies are mostly encountered as pairs in this area, so it was a treat to find this group of five birds hanging out with a flock of Common Goldeneyes. Oracle Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Two pairs of backlit Hooded Mergansers with males molting from eclipse plumage into breeding colors. Nob Hill Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Drake Hooded Merganser. Oracle Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

A winged Hippocamp or just an odd-looking duck? A drake Red-breasted Merganser (Mergus serrator) exhibiting its distinctive, “hairy” crest. Until last year, this large sea duck was considered to be the fastest-flying member of the family, with light plane chases of this species in level flight reaching 100 mph/160 kph. A turbo-charged migrating Mallard, also clocked by a cruising plane, now holds the speed record at 103 mph/166 kph. Coyote Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Red-breasted Mergansers are the only merganser species that favors marine habitats. They often dive for long periods while hunting their aquatic prey and usually pop up some distance from where they submerge. Coyote Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Red-breasted Merganser preparing to swallow a slippery Longjaw Mudsucker (Gillicthys mirabilis), an unprepossessing but aptly-named marine goby species. The serrated beaks of mergansers assist in catching and holding onto their aquatic prey. Because these ducks feed mainly on fish, they are known to accumulate industrial toxins in their tissues such as mercury, dioxin, PCB, and dieldrin so–quite apart from having an unpleasant fishy taste–these ducks are not recommended as table fare. Seal Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Drake Red-breasted Mergansers sport the original Punk Haircut. Coyote Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Drake Surf Scoter (Melanitta perspicillata) showing off his toucanet bill and pink feet. The SF Bay houses the largest population of migrant Surf Scoters anywhere but they are also easily observed in good numbers along the Pacific coast in winter. Unlike Black (M. americana) and White-winged Scoters (M. deglandi), which are seaducks that prefer deep water, this species is often observed very near shore. Coyote Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Pair of Surf Scoters. Coyote Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Surf Scoter drakes rubbernecking. Pillar Point Harbor, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

A small flock of Surf Scoters alongside the breakwater at Pillar Point Harbor. The brilliant white flash marks on the necks of the drakes are visible for long distances when floating out in the surf. Image: Jay Vannini 2025.

Partial view in a composite photo of a very large but well dispersed raft of migrant Surf Scoters staging in the San Francsico Bay north of the breakwater at Coyote Point at the end of February 2025. The flocks were strung far out across the water into the distance mostly towards the east–not visible but to the right in this image–and a count showed they numbered several hundred individuals. ~Sixty Surf Scoters shown in this image. A few days later there were none. Container ships moored directly north of this location awaiting entry to the Port of Oakland dimly visible upper left and 7.5 mi/12 km away across the SF Bay. San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

A pair of Surf Scoters catching a wave amidst heavy swell offshore in the Pacific Ocean at Mori Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Drake Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) in breeding plumage. Coyote Point, San Mateo County, California. This individual is likely the same drake that has been reported by local birders as an a seasonal visitor to this locality over the past several years. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Historically reported as a breeding bird along fast-running streams on the western slope of California’s Sierra Nevada, the status of Harlequin Ducks as a resident species is currently unclear. Scattered birds wintering on the California coast appear to originate from populations in Alaska, western Canada, and the Pacific Northwest USA. This individual was not included in my 30 day count because it was photographed in late February, so a few weeks past the self-imposed deadline. Coyote Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini

Harlequins are strong swimmers and divers that feed primarily on aquatic invertebrates. Coyote Point, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Acknowledgements

My fellow Esotericos Peter Rockstroh’s and Bill Lamar’s many outstanding articles on their backyard wildlife in Colombia and Texas provided the inspiration for me to–rather belatedly–get out and have a closer look at my own neighborhood fauna. For those interested in advanced bird photography techniques and tropical birdwatching, Peter has posted several excellent articles on the subject elsewhere on this website. Thanks also to Bill for suggesting the title for this article.

Common Goldeneye (Bucephala clangula) drake landing in the late afternoon at Oracle Pond, Redwood Shores, San Mateo County, California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

References

Bourke, I. 2024. ‘Unprecedented’: How bird flu became an animal pandemic. British Broadcasting Corporation-BBC. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20240425-how-dangerous-is-bird-flu-spread-to-wildlife-and-humans

Same old same old script from the BBC borrowed from the COVID pandemic, right down to trumpeting the adjective “unprecedented”. I assume the author was asleep in class when chytridiomycosis in amphibians was discussed, which has proved very much more than a flash in the pan. HPAI H5NI is rightly of great concern to wildlife managers globally but other than a limited number of admittedly alarming examples from 2022 to 2024, its current impact on wild bird and mammal populations may seem worse than it actually is thanks to over-amplification by the media.

Brady, C. and M. Weaver. 2024. 2024 California Waterfowl Breeding Population Survey Report. California Department of Fish and Wildlife Btanch/Waterfowl Unit. Sacramento, California. 17 pp. https://wildlife.ca.gov/News/Archive/cdfw-completes-2024-waterfowl-breeding-population-survey

Caliendo, V., N. S. Lewis, A. Pohlmannm, S. R. Baillie, A. C. Banyard, M. Beer, I. H. Brown, R. A. M. Fouchier, R. D. E. Hansen, T. K. Lameris, A. S. Lang, S. Laurendeau, O. Lung, G. Robertson, H. van der Jeugd, T. N. Alkie, K. Thorup, M. L. van Toor, J. Waldenström, C. Yason, T. Kuiken, and Y. Berhane. 2022. Transatlantic spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 by wild birds from Europe to North America in 2021. Scientific Reports, 12. Nature.com. 1-18. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-13447-z

Campagna, C., M. Uhart, V. Falabella, J. Campagna, V. Zavattieri, R. E. T. Vanstreels, and M. Lewis. 2023 (2024). Catastrophic mortality of southern elephant seals caused by H5N1 avian influenza. Marine Mammal Science, Volume 40 (1): 322-325. Paywalled. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/mms.13101

Center for Disease Control (CDC). 2024. 2020-2024 Highlights in the History of Avian Influenza (Bird Flu) Timeline. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/avian-timeline/2020s.html

Center for Disease Control (CDC). 2025. USDA Reported H5N1 Bird Flue Detections in Wild Birds. Through February 11, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/situation-summary/data-map-wild-birds.html

eBird. 2021. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. (Accessed various dates during January, 2025). www.ebird.org and https://ebird.org/region/US-CA-081

Ducks Unlimited. 2024. 2024 Waterfowl Population Survey Results. https://www.ducks.org/conservation/waterfowl-surveys/2024-duck-numbers#results

Haman, K. H., S. F. Pearson, J. Brown, L. A. Frisbie, S. Penhallegon, A. M. Falgoush, R. M. Wolking, B. K. Torrevillas, K. R. Taylor, K. R. Snekvik, S. A. Tanedo, I. N. Keren, E. A. Ashley, C. T. Clark., D. M. Lambourn, C. D. Eckstrand, S. E, Edmonds, E. R. Rovani-Rhoades, H. Oltean, K. Wilkinson, D. Fauquier, A. Black, and T. B. Waltzek. 2024. A comprehensive epidemiological approach documenting an outbreak of H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus clade 2.3.4.4b among gulls, terns, and harbor seals in the Northeastern Pacific. Frontiers in Veterinary Science. Vol. 11. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/veterinary-science/articles/10.3389/fvets.2024.1483922/full

23 authors on a single paper? Yikes!

Keawcharoen, J., D. van Riel, G. van Amerongen, T. Bestebroer, W. E. Beyer, R. van Lavieren, A. Osterhaus, R. Fouchier, and T. Kuiken. 2008. Wild Ducks as Long-Distance Vectors of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus (H5N1). Emerging Infectious Diseases. Vol. 14, No, 4. 600-607. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2570914/pdf/07-1016_finalR.pdf

Lavretsky, P. J. E. Mohl, P. Söderquist, R. H. S. Kraus, M. L. Schummer, and J. I. Brown. 2023. The meaning of wild: Genetic and adaptive consequences from large-scale releases of domestic mallards. Communications Biology, 6:819. https://www.nature.com/articles/s42003-023-05170-w

National Institute of Health (NIH). 2024. NIH officials assess threat of H5N1. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-officials-assess-threat-h5n1

Otesson, P. 2024. Migration Alert: Strong Early Good Duck and Geese Numbers have California Hunters Optimistic for Opener. Ducks Unlimited. Migration Map Oct. 17, 2024 - Pacific Flyway - California. www.ducks.org/hunting/migration-alerts/migration-alert-strong-early-duck-and-goose-numbers-have-california-hunters-optimistic-for-opener

Sorensen, M. D. 1997. Effects if intra- and interspecific brood parasitism on a precocial host, the canvasback, Aythya valisineria. Behavioral Ecology, Vol. 8, Issue 2: 153-161.

Sugden, L. G. 1980. Parasitism of Canvasback Nests by Redheads, Journal of Field Ornithology, 51 (4): 361-364.

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). 2024. APHIS Announce Updates to Indemnity Program for Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza on Poultry Farms. Animal and Plant Inspection Service. USDA, December 20, 2024. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/news/agency-announcements/aphis-announces-updates-indemnity-program-highly-pathogenic-avian

United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). 2024. Waterfowl population status, 2024. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. vi + 65. https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2024-08/waterfowl-population-status-report-2024.pdf

Vannini, J. 1994. Nearctic avian migrants in coffee plantations and forest fragments of south-western Guatemala. Bird Conservation International. Cambridge University Press, 4: 209-232. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/341C0AA159037BC1B1E689D016568A90/S0959270900002781a.pdf/nearctic_avian_migrants_in_coffee_plantations_and_forest_fragments_of_southwestern_guatemala.pdf

Yates, D. 2025. How are migrating wild birds affected by H5N1 infection in the U.S. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign News Bureau. https://news.illinois.edu/how-are-migrating-wild-birds-affected-by-h5n1-infection-in-the-u-s/

Withrow, J. J. 2023. Eurasian Wigeon Breed in the Aleutian Islands, Alaska. Western Birds, Vol. 54, Issue 1: 65.

TikTok Ducks? The drakes of most scoters (Melanitta species) have pale eyes and large, colorful bills that evoke over the top, disfiguring lip augmentations that are evident everywhere these days on social media, in advertising, and cinematic actors. The coal black plumage and white markings also call to mind vintage Daffy Duck.

Trout pouts for duck lips? “Dethhhpicable!” Image: ©Jay Vannini 2025.

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC® 2025, ©Jay Vannini 2025.

Follow us on: