Orchid Addiction? Tips to get Sobr (alia)

by Jay Vannini

Mention "Sobralia" to most orchid growers and they will probably groan and roll their eyes. To many, the genus honoring botanist and court physician to King Carlos IV of Spain, Dr. Francisco Sobral, conjures up images of large, reedy plants that take up an inordinate amount of space in garden or greenhouse, only to begrudgingly surrender a crop of miserably short-lived–if admittedly showy–flowers once a year.

Sobralia macrantha 'Anjelica' x leucoxantha in outdoors cultivation on my terrace in California. This is an outstanding large-flowered white selection for coastal California, exhibiting both heat and cold tolerance and very good individual flower life.

Sobralia is a fairly large orchid genus (~200 species) that is probably under-described throughout much of its range. The fragility and ephemerality of the flowers of most of the species (measured in hours in many cases), coupled with difficulties in preserving them in the field and the vegetative similarity of the plants themselves, makes it challenging to sample them adequately and invites mistaken identities in nature. One of the leading contemporary specialists in the genus, Dr. Franco Pupulin of the University of Costa Rica's Lankester Botanical Garden, has recently stated that he believes that the number of described species may ultimately double when more regional botanists take exhaustive, critical looks at their native orchid floras. It is now gradually becoming clear that some species-rich localities at intermediate elevations from Guatemala south to Venezuela and Perú may harbor constellations of florally distinct Sobralia species growing in sympatry, some (many? most?) of which may have been overlooked by visiting botanists. Dr. Robert Dressler, who is also very well-known for his longtime interest in this genus, reported 28 species of sobralias from Costa Rica in his 1993 field guide to that country's orchids. In 2017, in an article written together with Marco Acuña and Franco Pupulin, they document almost 40 Costa Rican sobralias and detail some of the difficulties of working with them. Further complicating this taxonomic puzzle is the fact that some species are now known or suspected to hybridize promiscuously in nature, most notably the well-known wild populations of central Guatemalan S. macrantha x S. xantholeuca, known in cultivation as S. veitchii = S. x Veitchii or S. Wiganiae. In light to moderately disturbed habitat these plants now outnumber the parent species at several accessible localities in the Verapaz Departments of Guatemala, and can produce a dizzying variety of flower sizes and color forms at some of these sites. This amazing variability in flower forms among some hybrid swarms that are subject to occasional poaching for the local ornamental trade has unfortunately led to the over-description of the genus in Guatemala, with several of these putative hybrids being described as full species based on unicates or flower color alone (e.g. S. cordovarum, S. euleri, S. laurisii, S. tubilabia, etc.), along with other quite good new species with very distinctive floral structures.

Sobralia cf. rogersiana in nature, lightly-disturbed tropical wet forest, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. Image: F. Muller

For those unfamiliar with them, sobralias are a group of (mostly) tall to very tall terrestrial orchid species - some exceed 35'/11 m in height - with handsome, bamboo-like stems and (mostly) large, exotic looking Cattleya-like flowers. Some of the smaller species are epiphytic, but almost all of the species can adapt to either lifestyle. Long popular as garden subjects with rural folks in Latin America, they were also favored by English collectors in the late 19th century, and the first hybrids were registered beginning in the 1850s. They more or less fell out of fashion from the beginning of the last century until the mid-1990s. After decades of being ignored by orchid growers and relegated to afterthoughts by tropical and subtropical gardeners, they are again finding an enthusiastic following in the US as landscape plants, particularly in southern California, Hawaii and south Florida. At present time they have their own special set of Fakebook followers and there are large numbers of images available online, mostly of plants in nature or just-out-of-the-box purchases from Andean country vendors. A few of the man-made and natural hybrids are lightly frost tolerant, with S. Mirabilis (a cross involving S. macrantha and S. x Veitchii) and its downstream hybrids, as well as several others survive outdoors in the SF Bay area to ~28 F/-2 C. A number of species of the recently-segregated genus of giant species, Brasolia, from high elevations of the NW Andean region, are extremely cold tolerant but - as a rule - exquisitely heat INtolerant.

Cloud forest Sobralia sp., probably aff. rosea in nature, Valle del Cauca province, Colombia. Image: F. Muller.

Mature specimen plant of Sobralia maduroi in year-round outdoors cultivation in California, synchronous flowering event July 2017 involving >250 flowers. Note that each stem carried two to four flowers simultaneously

Some problem sobralias and me. Perched on the far edge of enormous population of an apparently introgressed hybrid swarm of several Sobralia species in selectively-logged central Guatemalan cloud forest.

Unlike most Neotropical orchids, sobralias can be abundant and very conspicuous elements in the landscape, occasionally forming pure colonies on hillsides that can extend for several acres/hectares. Famed 20th century botanist Julian Steyermark noted on a herbarium sheet of a S. macrantha collection from the high elevation locality on Cerro Victoria, Huehuetenango Department, Guatemala that, "Covering slopes of a barranco and growing by the thousands of plants for several acres, associated with Quercus-Pinus...". I have observed this same phenomenon with S. macrantha growing as a terrestrial or lithophyte in the middle Río Samalá canyon and on the remote upper southern slope of Volcán Santa María, both in Quezaltenango Department, Guatemala, as well as a near pure mass of a hybrid swarm between S. macrantha and S. xantholeuca extending for at least three acres/>one hectare and probably numbering well over 10,000 individual plants in Baja Verapaz Department (see images). This phenomenon is again conspicuous at the summit of Cerro Gaital, Coclé Province, Panamá where, at about 2,900'/900 m mixed Sobralia species grow as colonies, fully exposed and albeit in smaller numbers than those just mentioned, but to the near exclusion of other emergent flora. A number of authors have also noted large sobralia communities in ecosystems as disparate the windswept upper elevations of the Peruvian Andes and the hot and humid Venezuelan llanos.

Edge of hillside densely populated with a wide-ranging colony of putative hybrid sobralias. The plants are visible above the rock face growing from upper left to lower right, Baja Verapaz, Guatemala. Ostensibly "pure"-looking Sobralia macrantha and S. xantholeuca are also present as individual plants on the margins of this community.

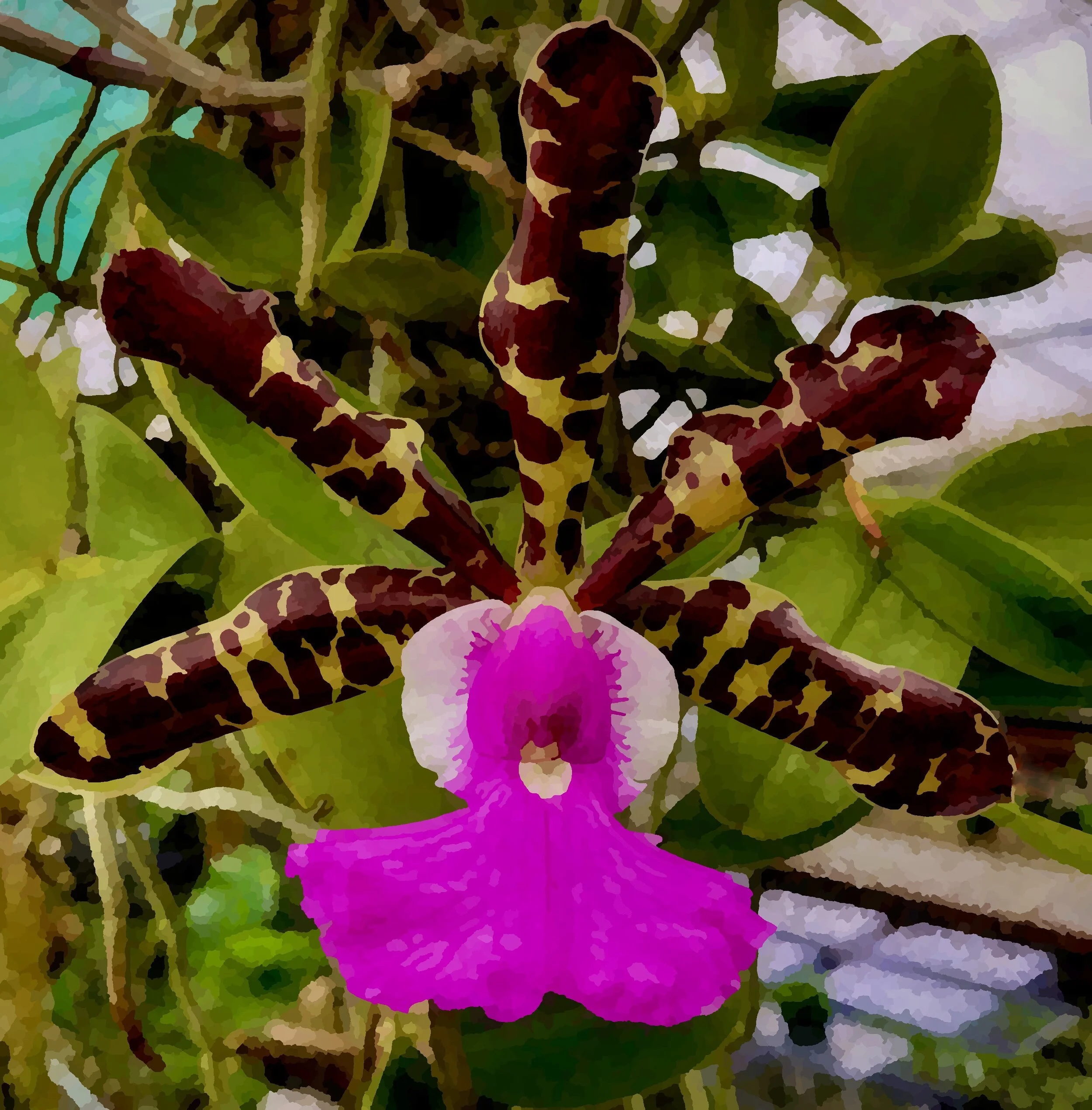

Sobralia flower detail from population shown above. This community shows a wide range of colors and sizes throughout, from pale pastels to saturated colors like this one. Flower form and size is also variable. This putative hybrid's flower matches S. "euleri" well. Image: F. Muller

Cultivated sobralias favor lightly shaded conditions, well-drained beds or pots, good ventilation, cool nights and lots of water to thrive. Besides amended soils when planted in the ground outdoors, they grow well in a variety of media suitable for orchids, including pure sphagnum moss, tree fern fiber, coco-crouton and conifer bark mixes. I find them to be fairly heavy feeders at all sizes, and should be adequately fertilized to grow and flower well. Some are remarkably tolerant of full sun exposure for long periods, particularly if prevailing air temperatures are usually cool. Plants are usually quite pest resistant but new leaves can attract aphids, thrips and mealybugs. The flowers and unopened buds are very attractive to slugs and snails and should be guarded from the attacks of these pests, which can ruin a long-anticipated flower crop in a matter of hours. Although the flowers are often large and showy, they are mostly ephemeral. While several species and hybrids have blooms that last three or four days in good condition, the majority are "one-day wonders", with at least a few (apparently not in cultivation outside of their native countries) lasting only two or three hours in the late morning. Luckily, they flower repetitively on the same stem, so a large plant may be in flower intermittently for from four to six weeks (or sometime much more - see comments on Sobralia andreae below). All of the S. dissimilis-undatocarinata-maduroi species complex from the middle and upper elevations of Costa Rica and Panamá have surprisingly long-lasting flowers when grown cool, often appearing in groups of three or four simultaneously from a single stem. The giant species with many-flowered inflorescences from northern South America can produce continuous, sequential flowering that lasts for a couple months.

Sobralia rosea, grower Bruce Rogers

There are closely synchronous flowering events in some Sobralia species in nature and in cultivation that are spectacular to witness, sometimes with hundreds of flowers opening at the same time. Again, because all or most of the plants in a single wild population may flower gregariously on the same day or morning, it would be pure serendipity that an orchid specialist happens to be there to witness it, collect and properly preserve specimens for later taxonomic analysis. Spent sobralia flowers blast and decompose in extremely short order, particularly when warm and wet, so all that is left 24-48 hrs after a mass bloom event terminates is gelatinous mush hanging on the end of the stems. Random collection of wild sobralia plants by both casual and commercial ornamental plant collectors who routinely forget or obfuscate their origins is one of the reasons why there are so many attractive-flowered, unidentified cultivated Sobralia species in hobbyists' collections in their range countries. These "orphan" plants do, however, often provide valuable clues to botanists about undetected local sobralia diversity.

There are now well over 70 species in cultivation in the U.S., mostly originating from accessions in Costa Rica, Panamá, Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador. Beginning in the late 1990s and early 2000s, several orchid nurseries in countries of origin made many horticulturally-desirable native forms available to growers worldwide, particularly Maduro's Tropical Flowers in Panamá, Orquídeas del Valle in Colombia and Ecuagenera in Ecuador. Plants are generally easy to reacclimate from bare-root import, but may take a couple years to replace damaged foliage and begin flowering on a regular basis.

A third color variation of the western Panamanian endemic, Sobralia maduroi, flowering in the author’s collection in July 2019. This is very close to the form that Robert Dressler misidentfied in his otherwise excellent summary on the S. undatocarinata complex published in the October 2004 issue of “Orchids”. On the day these images were taken, the plant was holding >130 flowers and fully-developed buds and had several inflorescences holding four flowers simultaneously. One remarkable aspect of this species’ flowers is that it emits a very strong and unmistakable fragrance of coconut oil-based suntan lotions.

Modern hybrids tend to be dominated by offerings from Hawaii (Ted Green), Southern California (James Rose) and central coastal California (Bruce Rogers). There are quite a few new hybrids that can hold good quality flowers for up to a week, and the overall plant size of many recent introductions has shrunk to easily manageable dimensions. There are now very nicely-flowered complex hybrid sobralias that have better temperature range tolerance and are suitable for bay window cultivation and tabletop display. Relatively recent crosses between unrelated species groups made by Bruce Rogers are yielding some exceptionally beautiful, interesting and fairly long-lasting flowers that are substantially different from past offerings.

This is one general direction in contemporary breeding, i.e. a very compact growth habit with intense purple or magenta, long-lasting flowers...

...and another that emphasizes eccentric flower form across a wide color palette.

Herein, a more or less representative selection of species and modern hybrids, mostly from my collections in Guatemala and California, but also a few from sobralia breeder par excellence, Bruce Rogers, with whom I have shared an opinion or three over the past six years. Fred Muller has also contributed a few of his typically excellent photographs of plants in nature, taken in Guatemala, Honduras and Panamá. My friend Edgar Mó of "Sobralia Paradise" (Cobán, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala) and his colleague José Monzón have also shared a few beautiful images of new species from that country.

White sobralias, both as white-flowered species and as alba forms of colored species and hybrids, are always popular with growers. A few select forms from my collections in both countries are shown below.

Latest-generation complex hybrid created by Bruce Rogers, Sobralia La Folie (=S. leucoxantha x xantholeuca) x dissimilis 'CUN'. These flowers are relatively long-lived and quite showy.

Shown below, some wild whites and near-whites growing as terrestrials in foothill and cloud forest of the Caribbean coast of Central America. All images save that of trio of Sobralia cobanensis: F. Muller.

Sobralia cf. chrysostoma, tropical rainforest, Atlántida, Honduras (Image: F. Muller)

A trio of beautiful examples of flowers from the same population of Sobralia cobanensis, a central Guatemalan, ephemeral flowered endemic described in 1999. The lower flowering plant was identified by a visiting orchid taxonomist some years back as S. warzcewiczii, while a local botanist considers all these plants to be examples of the different forms of S. "rosei", described in 2013. I share the view with some others in Guatemala familiar with the plant that S. cobanensis is a narrowly-distributed species with very variable flower color, sometimes splash-petaled (see elsewhere on this site), occasionally pure white. Its variability demonstrates the risks of describing new Sobralia species from single specimens or by flower color alone. Image: Edgar Mó

Sobralia cf. rosea flower, central Peru. Image: F. Muller.

Sobralia atropubescens, miniature form, Chiriquí, Panamá (Image. F. Muller).

Several noteworthy elfin forest and cloud forest localities on the Continental Divide in Panamá house exceptional Sobralia and Elleanthus diversity, particularly the smaller species. It is frequent to find more than a dozen species living in sympatry at these sites. It is a near certainty that both genera are under-described from both Panamá and Costa Rica.

The variably colored Brasolia dichotoma in nature, Huallaga Valley, Leoncio Prado Province, Perú. Image: ©F. Muller 2020.

Sobralia violacea, Venezuelan form.

Shown below are two outstanding clones of rose-purple flower colored species now in indoors cultivation year-round at my home in California. The Sobralia andreae clone shown below left has been in constant flower as a "houseplant" for the past 14 months while its same-sized sibling hasn't flowered once in a climate-controlled greenhouse!! Sadly, this central Colombian native is another "one day wonder" sobralia species, but this plant brightens up this corner of the living room every few weeks with groups of its spectacular flowers. The S. callosa clone is a tall form of what is usually a very compact (18"/45 cm tall) Panamanian epiphyte and often produces twin flowers from single stems. Both of these examples are about 3'/95 cm tall and show exceptional flower quality for their species.

Two more cultivated rose purples.

Two strikingly-colored, relatively recent finds by Guatemalan orchid researchers, José Monzón and Edgar Mó.

A well-flowered Sobralia Terry Root holding several triples on individual inflorescences. This is one of the finest modern hybrids out there with a compact habit and multiple, very showy flowers that last several days in good condition. Often flowers twice yearly. Many clones have flatter flowers with wider segments and overall better form than this particular plant but it put on a nice show nonetheless. Grower and hybridizer Bruce Rogers.

Then from purples, on into red tones, morphing to yellows...

Sobralia xantholeuca, the "mother of all yellows" from Chiapas, México through central Guatemala to western El Salvador and Honduras. Some exceptional forms of this species that I have handled from Huehuetenango Department, Guatemala have notably flat flowers to over 8"/ 20 cm overall span and very deep yellow color. I have not seen comparable flower quality nor color intensity in the U.S. Flowers of this species may last several days, but fully-developed plants can take up a lot of space if not contained. The mature wild plant shown below left is ~10'/2.9 m across.

Some less-commonly colored cream, yellowish or bronze-flowered species and hybrids. The odd lips of Sobralia dissimilis always remind me of ornate Viennese pastries.Despite its unusual flower color, it is closely-related to the blue and white flowered S. maduroi shown above. Another Panamanian endemic from the S. undatocarinata species complex.

Sobralia maduroi hybrid by Bruce Rogers. Exceptional, multifloral modern hybrid with enchanting fragrance of Coppertone suntan oil! Author’s image, June 2019.

Potted Sobralia wilsoniana, ex-Finca Dracula, Boquete, Panamá. Synchronous bloom, including twin flowers from single stem, in outdoors cultivation in Guatemala. Image: J.J. Castillo

Sobralia gentryi f. alba in outdoors cultivation trial in coastal central California. Unfortunately, S. gentryi is apparently not a frost tolerant species and this handsome mature specimen departed to orchid heaven during a severe cold snap in January 2017

For those interested in seeing different images of these plants cultivated in a tropical garden setting, there are additional images posted on this site of some of my plants in Guatemala under, "La Casa de los Cusucos". I will be adding new photos as fresh material, both captive and wild, flowers over the next few months. Please check in later this summer to see what's been added.

In the meantime, three parting shots...

My buddy Bruce Rogers, "The Orchid Whisperer" himself, seen here comfortably ensconced in his native habitat, contemplating one of his exceptional Sobralia rogersiana and a few nice S. mirabilis flowers.

Beautiful miniature Sobralia sp. from Tropical Pluvial Forest, Valle del Cauca Department, Colombia (Image: F. Muller)

Another of Bruce Rogers’ modern, fragrant complex hybrids, Sobralia La Folie ‘Fall Sunset’ x S. dissimilis ‘CUN’. Good size and color with nice form. Author’s plant and image.

The giant Brasolia dichotoma flowering in nature in Perú. Image: ©F. Muller 2020.

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC® 2018-2025, ©Jay Vannini 2018-2021 and ©Fred Muller 2018-2021.

Follow us on: