Paphinias - Neotropical Starfish Orchids

The Call of the Weird

by Jay Vannini

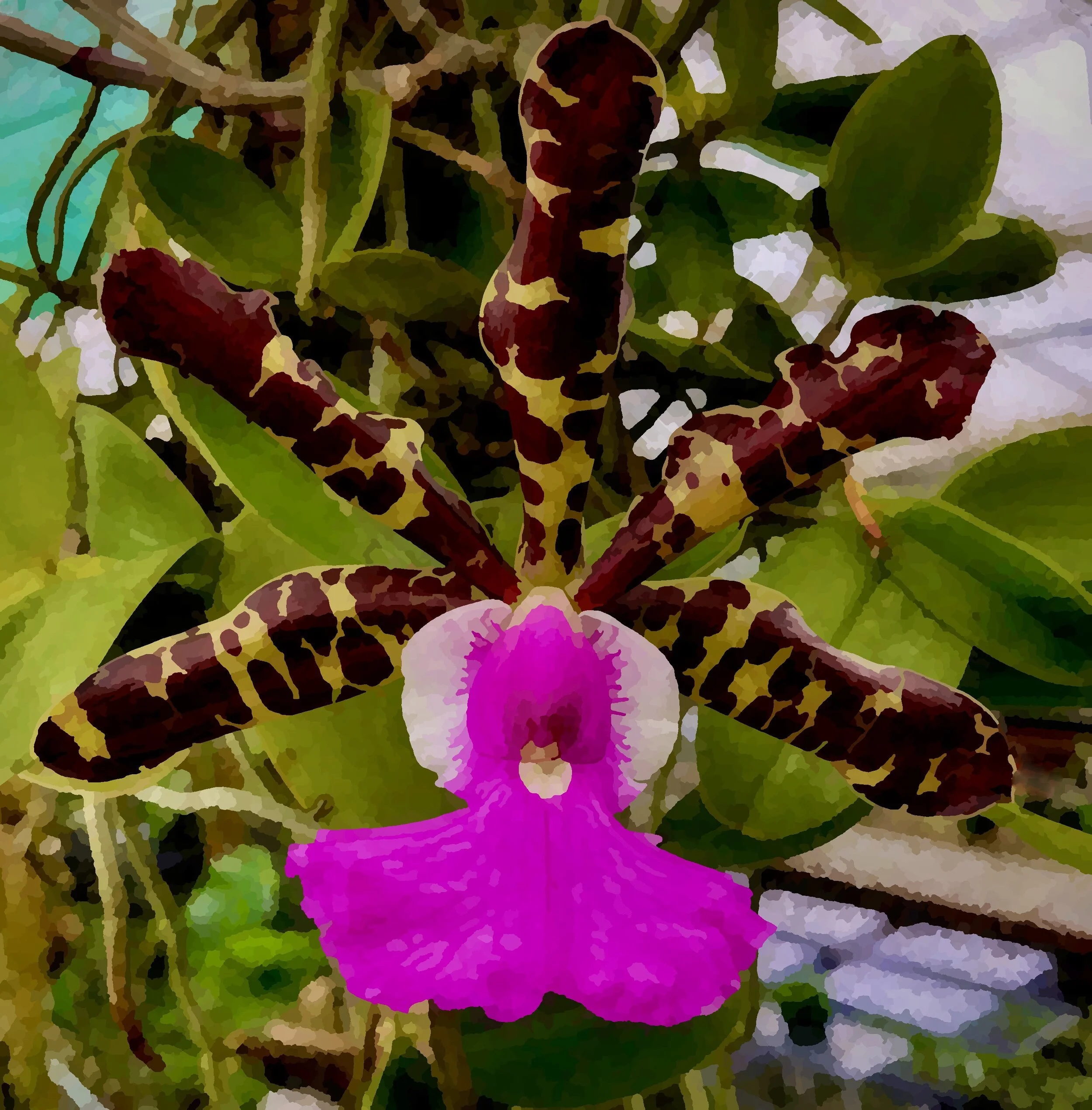

Paphinia posadarum flower details. Image: ©Ron Parsons 2024.

While tinkering with a few articles on arcane plants and archaeological sites that will (hopefully) materialize here sometime in the near future, I realized I was coming up on a deadline to post one this month. Casting about for inspiration for an interesting 1,500-worder, I noticed a couple very neat and rather unusual-looking orchid species I grow were getting ready to bloom at the greenhouse.

For the non-orchidophile, meet Paphinia Lindl. (Orchidaceae; Epidendroideae, Stanhopeinae).

A dozen backlit Paphinia neudeckeri buds and flowers opening in the author’s collection in California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

The genus Paphinia currently includes 16 accepted species that are distributed in lowland rainforests and middle elevation cloudforests from central Costa Rica to northern Brazil and Bolivia (POWO, 2024). They are trunk, branch, and twig epiphytes that inhabit wet, mossy environments in forest understories although there is one atypical terrestrial species from Amazonian Venezuela, Paphinia dunstervillei Dodson & G. A. Romero, that is also notable for having an erect inflorescence. The epiphytic varieties have also been collected growing on roadbanks where they are likely windfalls. Pseudobulbs are clustered and small, mostly under 2”/5” tall, and are topped by chartaceous, plicate leaves. Most species have comparatively large, short-lived, stellate (= star-shaped) flowers borne on pendant inflorescences that carry from two to nine flowers. Blooms are showy, ranging from just under 3”/7.5cm in diameter to more than 8”/20 cm across in large examples of P. herrerae Dodson. Among the few species that have been studied closely they are generally devoid of detectable scents to the human nose but do emit fragrances in minuscule amounts in order to attract their male Euglossine bee pollinators (Hentrich et al., 2017).

Paphinias lack a common name in English, which seems a regrettable oversight given their increasing popularity in cultivation. The flower forms of most species are quite reminiscent of marine starfish (Asteroidea), so “starfish orchids” would seems like a good proposal if not for the fact that it’s already taken by plants in the Old World Vandaceous genus Chiloschista. This is especially frustrating since the flowers of Chiloschista species look nothing like starfish!

Paphinia vermiculifera in cultivation in the USA. Plant collected in Panamá Province, Panamá. In herbaria this species is apparently known only from the type collections. Scanned from a 35 mm slide. Image: ©Ron Parsons 2024.

So, let’s run with Neotropical starfish orchids for now.

The generic name is based on Paphia (Classic Greek, Παφία), the surname of the goddess Aphrodite. This deity – better known as Venus in Roman mythology – is associated with beauty, desire, love, lust, and fertility (among others) so she is an apt and sexy fairy godmother for these elegant orchids.

Apart from their stellate flower form, these orchids possess the typical, conspicuously complex Stanhopeine reproductive parts one would expect, with conspicuous, club-tipped glandular fimbriations on their labella that are both key for determining the different species and to disperse chemical attractants for their pollinators.

In an early molecular study that included the Stanhopeinae published almost 25 years ago, a Paphinia species was placed alongside a Houlletia as sibling taxa (Whitten et al., 2000). Their flexible, pendent inflorescences and open flowers viewed from the side recall other better known members of the subtribe.

The genus

Paphinia cristata (Lindl.) Lindl. 1843, was the first species introduced to horticulture and published (as a Maxillaria) by a European botanist. It is also the widest ranging and most commonly cultivated member of the genus. It is known from the Meta Department of central Colombia northeast through Venezuela to Trinidad and Tobago, then east to French Guiana as well as south along the Andean foothills to northwestern Bolivia. Reported from Guatemala by Friedrich Schlechter (no locality cited) and cited in Ames & Correll (1953); this record is now generally accepted to be erroneous (Dix & Dix, 2000). Contemporary claims of its existence in Guatemala that lack voucher specimens are dubious (Gerlach & Dressler, 2003). Until the late 1980s and botanist Calaway Dodson’s publication of several new taxa from Ecuador, only four species were recognized, all having been described in the 19th century.

Paphinia subclausa Dressler is a small and white-flowered plant from central Limón Province, Costa Rica and is the northernmost occurring species. Paphinia seegeri G. Gerlach, endemic to the Chocoan lowlands of Colombia, is an outlier in terms of flower form and recalls other Stanhopeine genera such as Schlimia and (especially) Lacaena. See image of an inflorescence shown below.

The last published species that is currently considered valid was described in 2003. Paphinia vermiculifera G. Gerlach & Dressler, was reported to be endemic to El Valle de Antón and environs in Coclé Province, Panamá. A live plant collected on Cerro Jefe in Panamá Province several decades back and grown in the USA appears to represent this species (R. Parsons, pers. comm. - see image left). Like other orchid genera that appear to have originated in and dispersed from megadiverse ecosystems in the Colombian-Ecuadorean border regions, additional novelties are expected to be found and described as botanical exploration of these areas intensifies.

King Crimson - a large flowered Paphinia cristata selection grown in the author’s collection in California. Image (smartphone): ©Jay Vannini 2024.

Above left, the pendant inflorescence of a very close relative of Paphinia species, Houlletia tigrina, viewed from below. Image right shows a nice group of flowers of the bigeneric hybrid, xHoullinia Leon (H. odoratissima x P. neudeckeri). Plants grown by Hanging Gardens (L) and Marni Turkel (R). Images: ©Ron Parsons 2024.

Apart from Paphinia cristata and P. lindeniana, all other species appear to be rather narrow endemics and especially vulnerable to habitat loss. Ecuador is currently considered the center of diversity for the genus (eight species) with P. benzingii Dodson & Neudecker, P. herrerae Dodson, P. hirtzii Dodson, P. levyae Garay, P. litensis Dodson & Neudecker, P. neudeckeri Jenny, P. posadarum Dodson & R. Escobar, and P. zamorae Garay confirmed as natives. Colombia is a close second with six species known to occur in the country but may end up with several more when additional collections are made in the Chocó, the Amazonian lowlands, and the southern part of the country. Other than the pair of southern Central Americans, a few species range east and south into Venezuela and Brazil along the lower Amazon and on its tropical Atlantic coast.

Hybrids are few, the best known of which is Paphinia Majestic (P. cristata x P. herrerae) which, apart from red variants, also comes in alba and semi-alba forms. There are also some experimental intergeneric primary hybrids, including crosses with Stanhopea, Houlletia, and Gongora species.

Paphinia herrerae is notable for its flowers’ variable color forms that range from saturated pink and maroon to translucent yellowish-white in alba forms. Its striking, almost ghost-like appearance led to its being named the Provincial Flower of Zamora-Chinchipe, Ecuador by the regional government in 2014. This species has many admirers elsewhere and has been called “The Most Beautiful Orchid” by a former manager of Atlanta Botanical Garden’s Fuqua Orchid Center (Brinkman, 2012). While many orchid growers likely disagree with this opinion, fine examples of this species certainly possess extremely showy flowers.

There is a late 19th century illustration of a pure white flowered form of P. cristata (“var.” [sic] modiglianiana Rchb. f.) published in Lindeniana but it is unclear whether any P. cristata f. alba persist in cultivation today. A couple other species that normally have mostly red, white-tattooed flowers may also occasionally turn up dark, near-concolorous flower forms.

In cultivation

Until fairly recently the only species that was readily available in the ornamental tropical plant trade in the EU and USA was Paphinia cristata, or lookalike taxa mislabeled as such. By the middle of the 1990s another pair of species – P. neudeckeri and P. herrerae – became available on a regular basis from plant exporters in Ecuador. At this time, it seems that most cultivated plants are either one of these three species or their hybrids. More than half of the accepted taxa are now being cultivated outside of countries of origin but other than P. hirtzii, P. posadarum, and P. seegeri, others can be challenging to find available for sale in the USA (pers. obs.).

Neotropical starfish orchids are best grown in slatted wood baskets, plastic hydro net pots, and similar containers. They are occasionally seen grown in small treefern pots or mossed and mounted on cork plaques. Mature, specimen-sized individuals will require container sizes in the 8”/20 cm range. Like other Stahopeines with pendent inflorescences, these orchids should be monitored during the blooming season to prevent their inflorescences from spiking straight down on emergence and being lost as they descend into the substrate in search of an exit. Crunchy and durable bark-based substrates are my preferred growing media. Alternately, pure medium-grade treefern fiber and high quality New Zealand dried sphagnum moss seem to perform well for others. Amateur growers have commented on internet orchid fora that they grow their plants in mineral substrates such as diatomite or Japanese pumice, which seem quite unsuitable alternatives to me.

Paphinia herrerae f. alba. Grower: Marni Turkel. Image: ©Ron Parsons 2024.

I cultivate my plants (nine individuals of five species) under shady, warm, humid, “stovehouse” conditions with plenty of airflow running over the hanging plants. They are fertigated every 10 days to two weeks during the spring and summer and every three to four weeks at other times of the year. They are wet forest residents in nature so do not allow these plants dry out fully under captive conditions. Given their requirements, they are not suitable for long-term cultivation in northern homes although I do “spell” flowering plants in my kitchen bay window several times a year where they provide nice touches of color and floral weirdness.

Paphinia seegeri. Grower: Andy Phillips. Image: Ron Parsons 2024.

Neotropical starfish orchids can be fussy in cultivation if environmental conditions are not to their liking. Besides pseudobulb rots, bacterial and fungal leaf spotting may be a problem and need to be watched for in plants held in stagnant, humidity-saturated environments. While they resent root disturbance when large, I would watch closely for any evidence that the substrate is breaking down after more than a few years and repot immediately if this is observed to be case.

When well-grown, fully mature Neotropical starfish orchids will produce multiple inflorescences, and I have had individual plants hold as many as 45 fully-formed buds and open flowers simultaneously. There are images posted online with plants holding even higher flower numbers. They flower from the bases of their pseudobulbs repetitively over a month or so more, often three (or more) times annually in some species. Despite the short shelf life of individual flowers, which is usually only several days, larger inflorescences will provide quite a show for about five days under benign, humid conditions. Unlike most other orchids with elongated inflorescences, all the flowers on a single peduncle tend to open more or less simultaneously, rather than basally to apically over time as is usual in many familiar orchids.

Despite being one of the less-known Stanhopeine genera, Neotropical starfish orchids are fantastic creatures to have around the green- or shadehouse and well worth the effort required to grow them to perfection at specimen sizes.

In closing

Although I do not own it and have not yet had an opportunity to leaf through a copy, an authority on the genus, Rudolph Jenny, published a monograph on it a few years back. “The Paphinia Book” (2018) was privately printed by the author in Quito, Ecuador. Online reviews show it to be a well-regarded work by other Neotropical orchid workers. A sample chapter available online at his shop, Orchilibra, shows it to be thoroughly researched and illustrated. Well-heeled bibliophiles interested in further information on the genus may want to purchase a copy.

A interesting, high yellow color form of Paphinia rugosa. Grower: Andy Phillips. Image: ©Ron Parsons 2024.

Paphinia herrerae flower details. This is one of the most popular species of Neotropical starfish orchids in cultivation and is a parent of several primary hybrids. Large, well-grown specimens are spectacular display items when in full flower. Author’s collection in California. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2024.

References

Ames, O. and D. S. Correll. 1953. Orchids of Guatemala. Fieldiana: Botany. Vol. 26, No. 2. Chicago Natural History Museum. 399-727.

Brinkman, B. 2012. The Most Beautiful Orchid. The Orchid Column - Notes from the Fuqua Orchid Center. Atlanta Botanical Garden. 1 pg. http://www.theorchidcolumn.com/2012/10/the-most-beautiful-orchid.html

Dix, M. A. and Dix M. W. 2000. Orchids of Guatemala. A Revised Annotated Checklist. Missouri Botanical Garden Press. 61 pp.

Gerlach, G. and R. Dressler. 2003. Stanhopeinae Mesoamericanae I. Description of Paphinia vermiculifera. 27-29.

Hentrich, H., A. Dick, L. Hagenguth, and L. Preiss. 2019. Paphinia Lindl. (Orchidaceae: Stanhopeinae) – a genus of scentless perfume orchids? Paper given at the 22nd World Orchid Conference 2017, Guayaquil, Ecuador. 60-79. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335842945_PAPHINIA_LINDL_ORCHIDACEAE_STANHOPEINAE_-A_GENUS_OF_S

Royal Botanical Gardens Kew – Plants of the World Online (POWO). 2024. Accessed October 2024. Link: https://powo.science.kew.org/

Whitten, W. Mark, N. H. Williams, and M. W. Chase. 2000. Subtribal and generic relationships of Maxillariaea (Orchidaceae) with emphasis on Stanhopeinae: combined molecular evidence. Journal of American Botany. Vol. 87, Issue 12. 1842-1856. https://bsapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.2307/2656837

Acknowledgements

Once again, my good friend Ron Parsons has stepped up to the plate and batted a homer by generously providing several excellent photos of flowering Paphinia and Houlletia species cultivated in four well-known Californian orchid collections. I am much obliged for this courtesy.

Paphinia neudeckeri flowering in the author’s collection in Guatemala. This example is a vividly colored, very flat-flowered form of the species that is often misidentified on the internet as P. cristata. It is another popular hybrid parent. Image: Jay Vannini 2024.

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC® 2024-2025, ©Jay Vannini 2024, and ©Ron Parsons 2024.

Follow us on: