Phragmipedium kovachii and the quiet revenge of stolen beauty

“There is no trap so deadly as the trap you set for yourself.”

Raymond Chandler, “The Long Goodbye” (1953)

by Jay Vannini

Twinned 8.25”/21 cm very dark colored flowers on an artificially propagated Phragmipedium kovachii in the author’s collection in California. OK, so their form isn’t perfect but these flowers still stop jaded foot traffic in the commercial greenhouse that they’re grown in. Image ©R. Parsons 2020.

The shifting tides of taxonomy as a subject for cocktail party conversation, while close to the hearts of some of us, can be deadly dull and snooze-inducing to most. The inside baseball of advanced botanical taxonomy is, even to interested and well-educated growers of specialty plants, considered a dry, arcane topic best avoided at all costs. Where taxonomy usually spurs minor controversy and heated debate is when botanists have used new tools at their disposal–from karyotyping and protein electrophoresis early on to whole-genome sequencing now–as well as painstaking literature searches of early publications that often result in rearranged genera and the loss of familiar, long used Latin binomials near and dear to ornamental plant collectors.

But then…

Despite the seemingly unremarkable nature of the event itself, almost two decades back it was the christening of a single orchid species that launched the most notorious criminal investigation in the annals of plant conservation. In passing it also generated dozens of articles in popular media, one well-researched and commercially successful book, at least another unpublished manuscript by an insider, hundreds of heated internet exchanges, not to mention having had lasting and life-changing consequences for many of the participants.

Following a steady drone of noteworthy but mostly not very surprising orchid discoveries from throughout the world during the latter half of the 20th century, the 2000s opened with a bang as a giant, purple-flowered Neotropical slipper orchid, Phragmipedium kovachii, appeared out of nowhere to burst like a technicolor nuke in image attachments that short-circuited email inboxes of shocked and awed orchid growers everywhere.

While there are conflicting claims as to when this extraordinary plant was first discovered by local orchid growers, with some credible reports pointing to sometime in the 1990s, most published narratives usually mention the collections made by a subsistence farmer on his property near El Progreso, northern Perú in 2001.

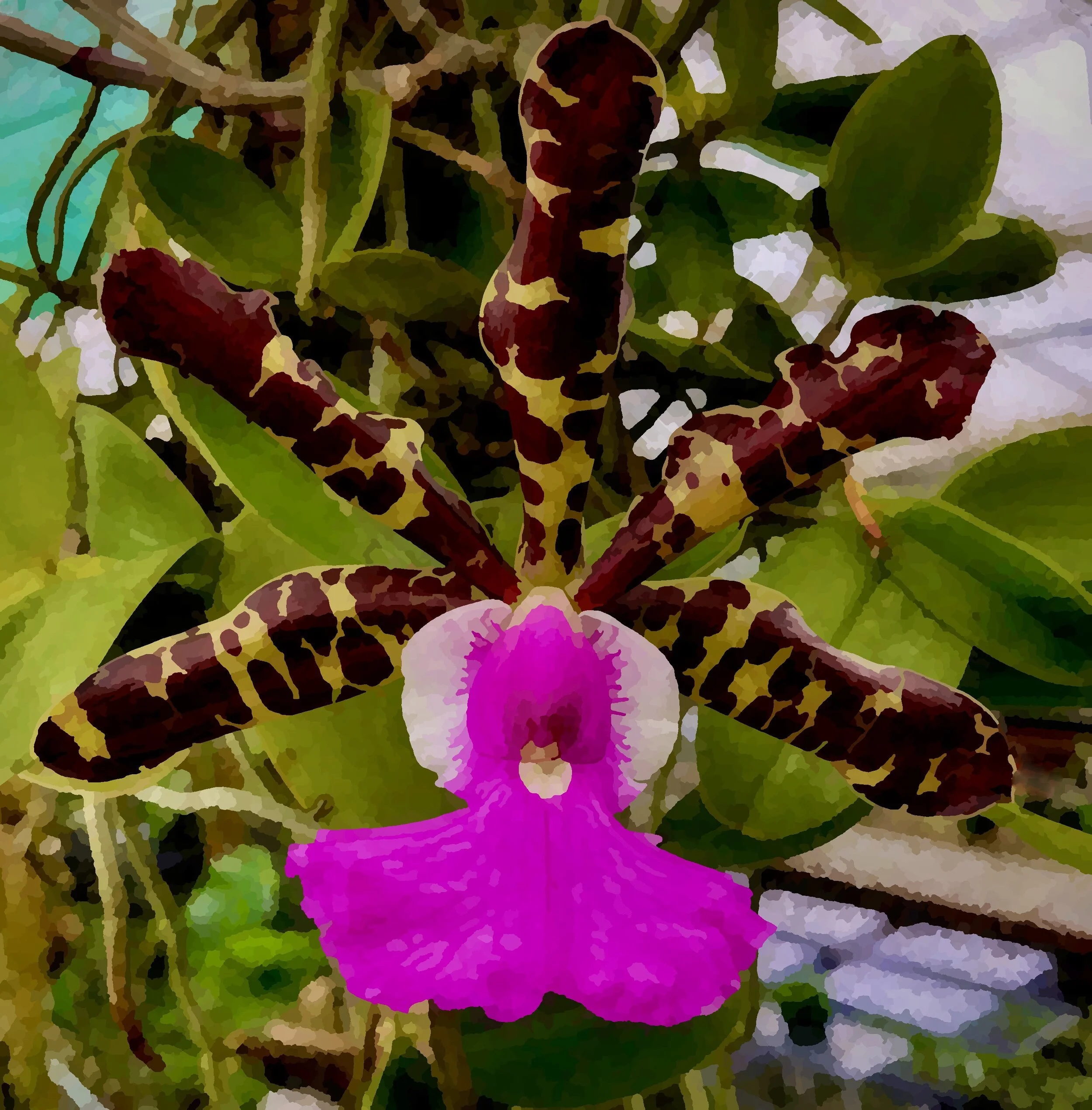

A very unusual color variant of Phragmipedium kovachi, sadly with mediocre flower form. Grower: Z. Zhou. Image ©R. Parsons 2020.

Either way, this story really begins in late spring 2002 when a trio of then unidentified slipper orchids were purchased for several dollars apiece at this farmer’s roadside stall by amateur orchid enthusiast James Michael Kovach. A few days later one or more were removed from the country without proper accession and export documentation then shipped to the U.S. in his accompanying baggage. At customs and immigration in Miami International Airport, together with other wild-collected orchids they were declared as “plants” on his sworn declaration but, due to an oversight by officials there, he was waived through with no inspection by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Hours after his arrival in Florida, a live flowering plant and a single partially desiccated flower were presented by him for an opinion as to its identity to a few staff and contractors at the Orchid Identification Center of Marie Selby Botanical Gardens in Sarasota. Immediately recognizing it as probably the most astonishing orchid discovery since Cattleya labiata (collected by Swainson in 1816 and described by Lindley in 1821), it was rushed into print a week later in a special edition of Selbyana (Vol. 23 Supplement, pp 1-4) authored by John Atwood, Stig Dalström & Ricardo Fernández.) This despite subsequent reports of inhouse doubts as to the veracity of parts of Kovach’s narrative and concerns about critical missing export permits in the documentation he later provided them. In addition, serious questions were raised by others at Selby regarding the wisdom of racing to publish the description of such a high profile CITES-regulated and perhaps critically endangered plant based on a type specimen that appeared to be of illicit provenance (Pittman, 2014).

Some controversy ensued.

This species is invariably introduced to readers to as the most remarkable orchid discovery of the last 100 years. Probably because some gran queso in the community said it first this statement has since become gospel. In passing, we are left to wonder what really are the orchid species published prior to 1902 that compete with this species in terms of its improbably showy aspect? I grow and have grown many standout orchid taxa over the past 40+ years and am also passing familiar with many rare and beautiful orchids in their native haunts in the Neotropics and elsewhere. To my mind a well-grown Phragmipedium kovachii holding exceptionally colored, multiple flowers with good conformation is one of the most striking and cupidity-inspiring of them all (but also see Cattleya aclandiae elsewehere on this website). Indeed, it may very well rank high among the list of the most surprising and unexpected botanical finds since the discoveries of Rafflesia arnoldii by Louis Auguste Deschamps (collected in 1797, published by Brown in 1818), Nepenthes rajah by Hugh Low (collected in 1858, published by Hooker in 1859) and Amorphophallus titanum by Odoardo Beccari (both collected and published by him in 1878).

A fairly fine quality flower on a F1 Phragmipedium kovachii. Grower: Z. Zhou. Image: ©R. Parsons 2020.

Despite variant opinions as to proper pronunciation of the species name among U.S. orchid growers, journalist Craig Pittman, who interviewed all of the main protagonists over the course of a decade, has clarified in his reporting that it should be pronounced ko-vahk-ee-eye. Jerry and Jason Fischer of Orchids Limited, individuals that seem to know as much about the backstory, propagation and cultivation of this orchid as anyone else outside of Perú, also pronounce the specific epithet this way in their videos posted online.

There was a major kerfuffle that arose immediately among orchid taxonomists and hobbyists when a competing orchid specialist, Eric Christenson, published the same species under the name Phragmipedium peruvianum in the American Orchid Society’s Orchids Magazine just five days after the article in Selbyana was printed. Because of this key issue with the dates P. kovachii, which was published first, has priority and P. peruvianum is considered a junior synonym. Despite indignant, pearl-clutching petitions from some to have the binomial changed since it was “tainted” by having been named in recognition of a U.S. national who later pled guilty to violating the Endangered Species Act, International Code of Botanical Nomenclature editors concluded that P. kovachii was validly published first and is therefore the correct binomial. In an article published in Taxon 56 (3) in August 2007, Selbyana editors Wesley Higgins & David Benzing handily dismiss the controversy surrounding the name, mount an articulate defense for it, and completely mop the floor with the author of an earlier proposal to suppress the species name P. kovachii (see Paul van Rijckevorsel’s piece in Taxon 55 (4), 2006 for an opposing point of view).

Eric Christenson died in 2011, so in all fairness he is not around to defend the decision-making process regarding his authorship of Phragmipedium peruvianum. That said, in my opinion he deserves plenty of criticism for his own role in L’affaire kovachii. It is certainly worth a raised eyebrow or two that he later admitted to never having seen his own original holotype, “flowered in cultivation in Peru” (Christenson #2056). This is not entirely surprising since it apparently no longer exists–if it ever did outside of his correspondence and manuscript–at the Universidad Nacional de San Marcos herbarium (USM) in Lima, Perú (fide Fernández in Higgins & Benzing, 2007). As further evidence of this error, in 2005 and well after the fact he subsequently designated a preserved flower provided by Peruvian nursery owner Karol Villena, assigned a number (7496-1) by his sometime collaborator David Bennett (d. 2009), and deposited at the USM as the true type specimen of P. peruvianum. This likely occurred when it seemed that the name P. kovachii might actually be suppressed in response to irate demands by some (see paragraph above) and his flawed description of P. peruvianum would be subjected to peer review and criticism.

Based on his decision to go solo throughout the publication process, Christenson and his editors certainly give the appearance of being culturally purblind. Notwithstanding it being an obvious point of concern given his later rants about the importance of “honoring” Perú, it seems no-one ever pressed him as to why there was no Peruvian coauthor on his paper (the Selbyana description does). As a practical matter, besides being a wise CYA policy he also received critical logistical assistance from both a Peruvian orchid nursery and a well-known botanist there. To my mind, far from being any sort of hero of this cast of characters, he was just as guilty of questionable, glory-hogging behaviors as those he routinely (and loudly) ascribed to his former colleagues at Selby.

Ironically, in yet another article published in Taxon 57 (2) in 2008 and penned by Blanca de León, Betty Millán (who was then Perú’s highest-ranking CITES official) and two other botanists at the USM, the authors note that Christenson’s designated holotypes of Phragmipedium peruvianum were also acquired by individuals who lacked a valid collecting permit, so, “…under Peruvian law both type specimens are associated with illegal actions…”.

Rumors circulate online of white-flowered and semialba forms of Phragmipedium kovachii growing in Andean country nurseries but photographic evidence remains lacking. In my opinion, pale flowered clones like this are interesting but definitely lack the panache of normal colored blooms. Admittedly, a pure white one would definitely be something worth having around. Grower: Z. Zhou. Image ©R. Parsons 2020.

The immediate scandal and its subsequent fallout saw plenty of asinine behavior on display by members of the orchid growing community as well as CITES authorities in the U.S. and (especially) the EU. Rather surprisingly, the sole set of relatively clean hands prior to Phragmipedium kovachii coming to market legally in the mid 2000s appears to belong to the Peruvian government’s National Natural Resources Institute, INRENA. After demonstrating understandable outrage over a clear-cut case of both the plunder of a unique natural treasure by a U.S. tourist and the scientific high-handedness showcased by some of Marie Selby Botanical Garden’s staff in its immediate aftermath, it was a group of officials at INRENA who pressed the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to pursue criminal charges against the parties involved for violations relating to illegal traffic of a plant obviously belonging to a CITES Appendix I listed genus.

Once the dust had settled a bit, INRENA very prudently set the wheels in motion for several local nurseries to collect limited numbers of wild founder stock to propagate P. kovachii from seed in Perú in order to reduce further pressure on wild populations. Despite considerable success in the intervening years by both Peruvian and foreign nurseries in bringing high quality seed grown material to market, there will always be individuals who opt to have wild collected plants on their benches. At this juncture they are presumably rather few in number, but they still create an unhealthy amount of demand.

Phragmipedium kovachii is currently considered to be lithophytic or terrestrial on calcareous substrates, patchily distributed and endemic to a fairly small area of lightly disturbed habitats in north-central Perú in the San Martín and Amazonas Departments between ~5,200 and 6,800’/1,600 and 2,100 masl. There are unsubstantiated reports that it also occurs in discrete colonies at other more distant localities kept undisclosed to the public in order to thwart potential poachers.

Following a visit to one of the earlier discovered, better-known populations by a group of U.S. orchid aficionados and their Peruvian guides in May 2003 (described at length in Koopowitz, 2003), the site was plundered by commercial interests who reportedly left no accessible live plants behind. Despite apparently unfounded accusations leveled against this visiting orchid tour by a couple local residents interested in stirring up controversy and resentment (anon., pers. comm.; Decker, 2007; Pittman, 2014), no evidence to support these claims ever surfaced. Based on comments by well-informed sources who point to track records of some well-known commercial interests at the time, it is now widely suspected that poached plants from this as well as several other sites ended up in regional nurseries as a first stop (anon., pers. comm.; Pittman, 2014). It is also rumored that the members of the Peruvian Orchid Society (SPO) and conservation authorities there are aware of who the offending parties were as well as the primary overseas destinations for “thousands” of poached Phragmipedium kovachii.

The criminal complaints filed by the U.S. Department of Justice for violations of the Endangered Species Act against Marie Selby Botanical Gardens, two of its employees and James Michael Kovach were resolved via plea bargains in late 2003 and mid 2004, respectively, and ultimately resulted in some public admissions of guilt, sentences of fairly short probation and negligible fines for three of the parties involved. Thus, the case ended on what seems rather a flat note for the Feds despite–no doubt–a boatload of money spent by the DOJ mounting their cases.

The reputational and financial damage done to everyone charged with a crime by the U.S. government was quite another matter and may have been an ancillary objective of the prosecutors from the beginning. The legal controversy and public debate that accompanied the description of Phragmipedium kovachii ended more than a few friendships, drastically changed some careers and tarnished the names of many more.

I will let better-informed readers draw their own conclusions as to who the real villains of this saga were.

James Michael Kovach, the lucky (?) plant collecting tourist who stumbled upon a vision from Paradise at a grubby roadside stall in rural Perú, was granted his wish and had THE orchid named after him in addition to many, many tales written about the consequences of this amazing find. Please see Oscar Wilde’s ironic observation on answered prayers. Unfortunately for Mr. Kovach and despite its undeniable beauty, “his” orchid will probably always be associated with misdeeds, notoriety and disrupted lives rather than endless accolades and a huge monetary windfall resulting from its discovery.

Of greater lasting harm was that done by Kovach’s decision to involve Selby in his self-promotional scheme and their own short-nearsightedness in allowing a completely unknown individual close enough to presume to traffic in this relationship. Botanists and botanical garden employees are now understandably leery of anyone walking through their doors with any endangered or CITES-listed plant of questionable provenance, no matter how tempting and remarkable it might be. The specter of the U.S. government threatening taxonomic botanists and botanical garden administrative staff with lengthy prison sentences and financial ruin has had an understandably chilling impact on the relationships between many public gardens and private collectors. Sadly, this damage is probably permanent.

Despite all of the hubbub surrounding its discovery and naming, subsequent events have proven rather anticlimactic.

Phragmipedium kovachii 'Leonardo André' FCC/AOS (90 pts), awarded Best of Show at the Pacific Orchid Exposition in San Francisco in 2014. Grower: Peruflora. Author’s image.

Seedling flasks of Phragmipedium kovachii from Peruflora were first made available in 2005 at the World Orchid Conference, held in France that year, and generated a brief new set of controversies. The first legal flasks appeared on the U.S. market in 2006 from Piping Rock Orchids in New York, originating from Centro de Jardinería Manrique of Lima, Perú. Orchids Limited in Minnesota introduced them in 2007, followed by another small nursery, both from Peruflora origin seedlings. Legally imported young plants were first sold at the World Orchid Conference in Miami in 2008 by a separate Peruvian source. The first legally imported plant grown from flask to flower and be judged in the U.S. won Best in Show at Wisconsin’s Orchid Quest in 2009. The first award quality flowering P. kovachii I saw was displayed by Peruflora in February 2014 at the Pacific Orchid Exposition in San Francisco, California and shown right also wowed visitors and won Best of Show.

And so on and so forth.

For almost six years I shared a greenhouse facility with several private orchid growers who also had high quality, legally imported examples of this species in their personal collections. One of them had invested heavily over the years in purchases of many exceptional clones from a wide variety of licit sources in Perú and the U.S.. This individual also ended up with a very substantial number of line bred seedlings that came to market when the Orchid Zone in Castroville, California finally shuttered in the summer of 2017. So, despite admittedly limited personal experience on my part growing this species from seedlings, I have watched many dozens of select Phragmipedium kovachii (as well as its hybrids) develop and flower since 2014.

Compot of established, imported seedling Phragmipedium kovachii in a low profile 5”/13 cm terra cotta pot with a plastic water-filled tray underneath. Author’s plants and image.

My oldest plants were purchased from Peruflora as a group of about a dozen 1.2-1.8”/30-45 mm seedlings sold loose in a Ziplock bag in February 2013. My results growing artificially propagated seedlings to maturity mirror that of many others I have spoken to, i.e. about seven to eight years from seed sow to flowering with almost all losses skewed towards the early years. I also have a pair of second-generation siblings from a selfing of an AM/AOS awarded plant (‘Rebecca’) that were gifted to me by a friend as ~4”/10 cm fans in mid 2019 that appear to be growing at about the same speed. They are both ~8”/20 cm in diameter as this was written, just starting to offset and are shown below.

Phragmipedium kovachii is mostly fall and winter-blooming both in nature and in the northern hemisphere. In the San Francisco Bay Area, plants flower from September through April with peaks observed from November to February. Flower color is most intense between 48 and 72 hours after opening when configuration is also at its best. Some examples can exhibit very saturated magenta or Tyrian purple coloration when first expanded. At time of this posting the best flower forms tend to be around 6”/15 cm wide with round, flat pale violet or medium purple petals, pink or pale violet dorsal sepals, intense velvety purple color on the pouch with bright yellow highlights and very flat profiles when viewed from the side. Larger flowers, some of which are shown throughout this article, tend to outgrow the support provided by their sepals and flex to varying degrees after the first few days. In extreme - but apparently rare - cases the petals may quill and this will end up ruining their appearance.

First flowering on a seed-grown Phragmipedium kovachii in the author’s collection in 2019. Newly opened flowers of this species are often very saturated in color with both satin and velvety aspects. Image: ©R. Parsons 2020.

Most plants in cultivation seem to produce single flowers, but larger examples can produce two or (rarely) three flowers on an inflorescence. Large plants with multiple fans can flower several times over the course of four or five months, so mature plants should not be broken up if growers want to enjoy flowers throughout the fall and winter. Blooms can last 10-14 days in excellent condition under optimal conditions but will rapidly blast if exposed to extremely high temperatures or very cold water.

Nearly nine year-old from seed sow, specimen-sized Phragmipedium kovachii growing and flowering in a mineral substrate in a 9”/23 cm plastic basket. This plant holds almost a dozen fans in various stages of development and is expected to flower over a five month stretch. Healthy, well established plants like this offset freely. Author’s plant and image.

Based on a single successful pollination of my one of my flowering plants in late 2019 and comments by others who have produced viable seed it takes about 120 days from pollination for a fully developed green pod to be safe to harvest. My pod developed during winter and early spring in a cool tropical greenhouse, but ripening times can be 20 or more days shorter if they coincide with warm weather (J. Rose, pers. comm.).

A pair of eight year-old domestically produced F2 Phragmipedium kovachii in 4”/10 cm baskets growing in the author’s collection. This species is markedly easier to grow once it exceeds this size. Author’s image.

This species is widely reported as being very slow growing from compot to ~4”/10 cm leaf span but progress steadily after that with adequate care. My own rather limited experience, together with observations of others’ success (or not) with larger numbers of seedlings and young plants, suggests that most mortality occurs between 2” to 3”/5 to 8 cm with only one plant lost by me for unknown reasons at ~10”/25 cm fan diameter. Despite some wild plants and etiolated cultivated specimens achieving >3’/95 cm wingspans, specimens I have seen grown and flowered under fairly bright conditions do so around 20”/50 cm fan diameters. Almost all of the plants I have observed offset freely, even when small.

Currently, exceptionally large flowers in Phragmipedium kovachii are known to reach 9”/23 cm in petal diameter and are a genuine spectacle to see in life. To me it seems a given that ongoing line breeding and chance or induced polyploidy - as has been the case with P. besseae - will produce (or already have) some award-worthy P. kovachii with >10” flowers.

Twinned flowers on one the author’s plants, both in good condition. When fully mature, Phragmipedium kovachii often develop two-flowered inflorescences although they usually mature a couple weeks apart. Image: ©R. Parsons 2020.

Recommended substrates: Based on my read of what successful growers were using at the time, I started my seedlings in coarse grade diatomite and fine Orchiata bark and grew them in compots with this mix standing in a shallow water filled tray for the first 18 months. I then experimented with a medium Orchiata bark, crushed oyster shell and perlite mix for a year before finally settling on medium grade hyuga, akadama, and charcoal in 2017 in hydro-baskets, top dressed with granular dolomitic limestone and 180 day nutricote. Under my conditions, this substrate has proven to be a winner. Unlike most other plants I have seen, my mature examples are grown hanging at midday light levels ~800-900 fc. I water copiously so have not bothered using a flood tray system since my plants were small seedlings. According to Jason Fischer’s (Orchids Limited) comments and videos posted online in 2019, it seems that after considerable experimentation on their end they have opted for either bark, perlite and charcoal mixes or stone wool cubes in combination with pots that maintain the roots constantly moist. Certainly, my experience is that the leaves will brown tip in short order if the roots are left to dry out for even brief periods of time. Pure water in large volumes, as is the case with many rather delicate cloud forest plants, is key to success.

Several nursery owners’ comments, together with my own experience with this species support the recommendation that it is important to boost calcium, magnesium, and iron inputs when growing Phragmipedium kovachii (Manrique, 2008). Frequent, low dose fertilization alternating with drenches of mineral free water are also key to success with this plant.

Above left, a green mature seed pod from a sibling cross on one of the author’s Phragmipedium kovachii at ~120 days after pollination. Right, a two year-old flask of seedlings grown from pod shown left in April 2022. Author’s plants and images.

For a while in the fairly recent past it seemed every online northern orchid vendor of any size had these plants for sale from either Peruvian, Ecuadorean, U.S. or German producers. During the summer of 2019, it was commonplace to see unflowered, iffy quality young Phragmipedium kovachii fans being auctioned or sold outright on eBay for as little as USD 100.00. These plants appear to have disappeared from the mass market by mid-2020 and once again prices for previously flowered, fair to good quality P. kovachii have crept back towards a USD 400.00 to 500.00 price point. Flasks are currently (2020) available online for ~USD 150.00 plus mailing from at least one U.S. nursery.

A representative tray of Phragmipedium kovachii F2 seedlings from select parents in my collection at 30 months post seed sow in early fall 2023. Plants are being grown on an open, cool greenhouse bench at 800 fc in 3”/8.5 cm cube pots containing a mineral substrate amended with fine conifer bark and dolomitic limestone. While seedling mortality from flask (see previous images) to potting out as individual seedling was unacceptably high in this batch (me culpa!), once the survivors had acclimated to pot culture their growth seems fairly rapid. Several plants visible here with 5”/12.5 cm leaf spans. Author’s plants and image.

Phragmipedium kovachii was used extensively to create novelty hybrids since its discovery. Early hybrids were generated by two well-known Peruvian nurseries, but later work has been done by many slipper orchid breeders in the U.S., the EU and Ecuador. While several produce very attractive flowers and are certainly easier for most hobbyists to grow than the pure species, there are many crosses that are surprisingly mundane. The results of many shotgun crosses made early on by putting pollen from almost any other phrag onto P. kovachii and vice versa once again vindicates the wisdom of thoughtful planning when breeding plants. While it is indisputable that some of the hybrids are interesting-looking, none are anywhere as good-looking as the pure species.

Which begs the question: “What’s the point” of these hybrids?

Shown above left, Phragmipedium Saltimbanco, a Peruflora primary hybrid of P. kovachii x P. boissierianum var. czerwiakowianum. Grower: Tom Perlite, Golden Gate Orchids. Author’s image. Above right, P. Eumelia Arias (P. kovachii x P. schlimii), another hybrid originally created by Peruflora but remade by a number of other breeders. Grower: C. Wong. Author’s image.

Phragmipedium Fritz Schomburg, an early, variable and very popular primary hybrid blending P. kovachii and P. besseae. Display plant at SFOS’s Orchids in the Park 2012. Author’s image.

So, did this scandal have a chilling effect on slipper orchid poachers and smugglers?

Apparently not, since both wild collected Phragmipedium and Paphiopedilum species continue to be sold ever since on a more or less open basis on the internet and elsewhere.

In 2019 I saw a number of large colonies of obviously wild-origin Phragmipedium andreettae, some with large chunks of native mineral substrate and moss still clinging to their roots, being sold by a foreign vendor at a U.S. orchid show. I know of one individual who, unaware of their clear and illegal wild provenance, purchased most of these plants. Almost all of them died within a year. Echoing Christensen’s description of P. peruvianum, P. andreettae was described from flowering material ex-horticulture claimed to have originated from an unknown locality in northwestern Ecuador (Cribb & Pupulin, 2006) with the type material deposited in the herbarium of the Universidad Católica de Ecuador in Quito (QCA). Based on a real-time literature search, comments by regional orchid researchers and as far as I am aware, there are no reliable reports of it having been found in the field in Ecuador ever since. The species is now believed to be narrowly endemic to riparian habitats in middle elevation forests of western Colombia in the Cauca and Valle del Cauca Departments (Braem & Tesón, 2016; Braem & Tesón, 2017), in particular one specific area that is well known to botanists, ecotourism guides and (perhaps not coincidentally) regional wild plant traffickers.

Phragmipedium andreettae ‘Fox Valley’ x self. Recent fieldwork in Colombia suggests the horticultural origins of this beautiful miniature slipper orchid should be re-examined. Upswept or slightly incurved petals are typical for this species. Author’s plant and image.

DNA analysis of the type material at QCA and comparison to that of specimens of known, wild-collected provenance from western Colombian sites and held in Colombian herbaria may prove enlightening as to the origins and relationships of the plant/s used by Cribb & Pupulin to describe Phragmipedium andreettae from a widely disjunct population in 2006. Any new reports of P. andreettae from nature in Ecuador should be subjected to similar scrutiny to dispel any doubts as to their origin.

The collection of wild tropical slipper orchids for commerce is not an infrequent, fairly benign practice that relies on salvaging a few plants from slash and burn plots or roadcuts for sale to local and international markets; this is straight up vandalism of natural patrimony that is repeated in the Neotropics, the tropical Asian mainland and insular Malesia, almost certainly in large numbers and on a constant basis. This traffic now has coveted, narrowly distributed species such as Phragmipedium fischeri and other slipper orchid taxa teetering on extirpation in nature.

See the Fundación EcoMinga website online for conservation efforts they are implementing to try and save dwindling populations of P. fischeri and other rare slippers in Ecuador.

Past evidence suggests that you can’t really write much about Phragmipedium kovachii without irritating a lot of people, but it is such a remarkable orchid species that it’s impossible to ignore if you own it. Organisms like this seduce even the best-intentioned individuals to succumb to temptation and bend or break the rules. Because of this, I am extremely reluctant to dwell on apparently minor failures of judgement by Selby employees and contractors back in 2002. Frankly, even if I were so inclined–and I am not–why should I? There are any number of self-righteous scolds who never seem to tire of harping on them.

As has been pointed out by others in the past, moral outrage is often nothing more than disguised jealousy with a clip-on halo.

Since I am also not especially keen on courting irately-worded email messages from any of the principal actors in the Phragmipedium kovachii naming debacle that are still alive and kicking, I refer readers interested in reveling in the better-documented dirt, spicy rumors and vitriol-soaked emails to read two excellent deep dives done by Craig Pittman that are referenced throughout this article: “The Case of the Purloined Orchids” (Sarasota Magazine, 2005) and “The Scent of Scandal” (University of Florida Press, 2014). In my opinion, the latter publication is probably the most insightful and best investigative piece profiling the contemporary U.S. orchid collecting scene written to date. As an experienced journalist who has reported extensively on environmental issues in Florida, Craig Pittman’s bullshit detector is evidently top-of-the-line. After reading his books and articles it seems clear to me that he needed it handy at all times as he interviewed almost everyone involved in this case.

And again on the illegal plant trade

Commercial scale plant poaching and plant poachers are a hot topic once again among rare plant growers and the media. Chat groups on internet plant fora show that a growing number of buyers in northern countries are slowly coming to realize that some of their pampered, recently imported acquisitions had spent their previous lives basking in the desert sun, anchored stream-side or rooted down in the rainforest understory and were not sown in a lab nor seeded on a greenhouse bench.

While some plant collectors seem uneasy at the thought that their purchases may be fomenting trade in illegally collected threatened flora, others shrug it off with arguments that habitat destruction is killing them anyways so they are safer in plant collections in the north, etc. There is no doubt that encroachment of the agricultural (esp. oil palm) and industrial frontier (petroleum and natural gas exploration, open-pit mineral mining, etc.) is producing massive and probably permanent losses of highly biodiverse ecosystems throughout the tropics, but the argument that rare, wild origin plants are “better off” in most amateur gardeners’ hands is sophistry, pure and simple. Quite apart from the fact that the available anecdotal evidence suggests that the overwhelming percentage of delicate imports are dead in fairly short order, anyone even passingly familiar with the origins of many of the rarer or undescribed species now trafficked from nature is aware that a lot of these plants are not being “rescued” from a recently logged area, but are in fact being filched from climax or lightly disturbed ecosystems on protected public, private and indigenous lands. This, if for no other reason than that is now where remant populations are most common, conspicuous and accessible.

If you still doubt this is occurring, please refer to the recent findings of Operación Atacama, a joint Italian-Chilean criminal investigation into wholesale poaching and smuggling of narrowly endemic Chilean cacti from Pan de Azúcar National Park and other regional localities by foreign nationals (clicking on this link to a IUCN article that will take you offsite; use backbutton to return to this article: https://www.iucn.org/news/species-survival-commission/202012/operacion-atacama-recovery-trafficked-threatened-cacti ). This lengthy investigation into wild plant theft and the aftermath was reported on by the New York Times (NYT) in an article published on May 20, 2021. A followup article in the same newspaper on wholesale poaching of rare conophytums in South Africa and Namibia may be read here: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/31/world/africa/south-africa-poachers-tiny-succulent-plants.html .

Both NYT pieces mention a disturbing phenomenon that anyone paying attention to the darker corners of the global rare plant trade has been aware of for some time: That specific threatened plant species–or in some extreme cases, very old individual wild specimens–are being targeted and “poached to order” via postings on social media and through instant messaging apps.

The view that individuals and entities in the north are better stewards of the natural resources of tropical countries than the people of those nations and are thus entitled to plunder them willy-nilly for commercial gain is–to put it mildly–patronizing, neocolonialist and rapacious. It is neither a clever nor original insight, but rather a spavined argument that drove the sacking of natural resources in the south for hundreds of years. This kind of commentary posted in rare plant fora on social media rightfully pisses off many residents and conservation authorities in the developing world. While everyone is free to express their personal opinions, mine is that defense of this rationale in particular is not at all helpful in improving the rapport between plant collectors and bureaucracies, nor in facilitating the issuance of permits for regulated commerce or for scientific research. By design or not, it also emboldens commercial plant poachers by providing them with false cover.

At this point it would be hard to refute that most everyone who purchases direct imported or flipped, recently imported ornamental plants knows whether or not they have acquired freshly collected and bench-laundered examples of wild flora of questionable provenance. The principal commercial sources of these plants, both in the New and Old World, are well known. Indeed, some suppliers of rare flora are not at all shy of boasting of this via “lookie here” posts made on social media that show obviously freshly collected material on their shadehouse benches looking exactly like freshly collected material on their shadehouse benches (see paragraphs above). Gardeners and collectors in the north who consider themselves environmentally-aware may want to weigh the impact of their purchases on wild populations of rare plants, and the damage to fragile ecosystems that commercial plant poaching often leaves in its wake.

It’s a Brave New World for all, but no fun whatsoever if you are a charismatic wild plant or animal species “outed” on social media as a must-have trophy.

If you’re still cool with underwriting this plunder, for now it’s a laissez-faire marketplace so, by all means, have at it folks. But be aware that history will not be kind when it judges your behavior.

A very large Phragmipedium kovachii flower on an imported plant that maintained fairly good form for more than 10 days. Grower: Z. Zhou. Author’s image.

In closing

Fifteen years after having first been made legally available to orchid collectors outside of Perú, Phragmipedium kovachii has now been artificially propagated by the many tens of thousands and well into select third generation plants by growers around the world. Far from the price levels of USD 5,000.00 to USD 10,000.00 first demanded for wild collected and smuggled plants, at current price points for unflowered single fans it is mostly within the budgets and cultivation requirements of many experienced tropical plant collectors genuinely interested in growing it. One of Nature’s most spectacular floral creations, P. kovachii has thrived in captivity and (somehow) managed to survive multiple assaults on native populations since its discovery. Admiring a well flowered, leaf perfect, artificially propagated P. kovachii in cultivation one is left to ponder the misfortune visited on those at the beginning whose main interests in them were to burnish their résumés and fatten their wallets.

Karma, as they say, has everyone’s address.

Hasta luego,

JV

Many thanks to Ron Parsons for making some of his fabulous images of cultivated examples–including some of mine–of this species and its hybrids available for this article. Thanks also to Tom Perlite of Golden Gate Orchids for helping to rescue seedlings from early incompetence on my part as well as the Peruvian nursery and U.S. laboratory that supplied the Phragmipedium kovachii specimens that I am fortunate to grow. And again thanks to James Rose of Cal-Orchid for facilitating in vitro seed sow of my select crossed material produced in the spring of 2020 that was returned to me in the form of perfectly grown seedlings in flasks two years later.

Other orchid growers have popularized the use of U.S. paper currency as both joke props to illustrate the impressive flower sizes that Phragmipedium kovachii can attain and to make a not-so-subtle point as to its monetary value. Here is a 10 day-old flower on one of the author’s plants (also shown at the top of the page) showing off its >8”/21 cm petal span, Benjamin Franklin looking on. Author’s image.

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC® 2020, ©Jay Vannini 2020-2023, and ©Ron Parsons 2020.

Follow us on: