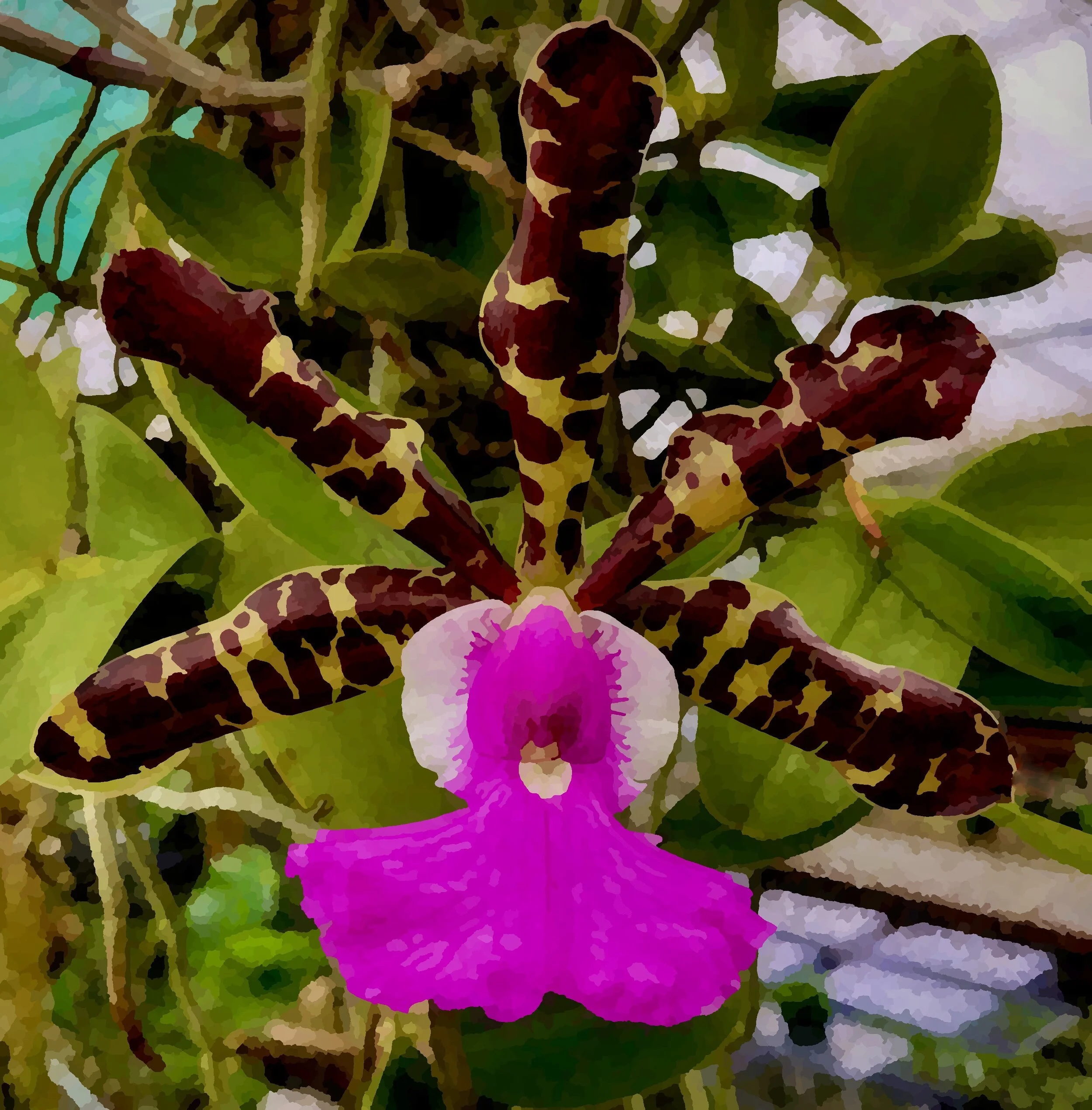

Cattleya aclandiae - The Leopard Print Boss o' Bossa Nova

by Jay Vannini

A very showy pair of Cattleya aclandiae flowers grown by Ramón de los Santos. Image: ©R. Parsons 2020.

Brazil is famous for its many outstanding orchid endemics, perhaps most so for the remarkable diversity of showy-flowered members of the Laeliinae subtribe that occur there. Although Cattleya is the largest and best-known genus in this group whose center of diversity is located in Brazil, Sophronitis (whose nomenclature is dealt with elsewhere on this site) is a near endemic, closely related genus that is also very popular in orchid collectors around the world.

Most of the best known Brazilian Cattleya species are medium to large-sized plants (e.g., C. labiata, C. tenebrosa, C. purpurata, and C. amethystoglossa). However, since what were formerly known as rupicolous Brazilian Laelia species have been lumped into this genus, it now also includes many true miniature species such as C. lucasiana and C. bicalhoi.

There are a pair of noteworthy epiphytic Cattleya species from the coastal and foothill forests of Brazil’s eastern Bahia and Espírito Santo states that combine compact plant size with comparatively huge, brightly colored and exotic-looking flowers. Both are now reportedly rare in nature and restricted to coastal, riparian habitats in open canopy tropical dry forests at elevations under 2,600’/800 masl. Cattleya aclandiae is the better known and more desirable of the two, but certainly less amenable to amateur cultivation. The somewhat similar-looking C. schilleriana is fairly easy to grow and flower and is well-established in captivity. Wild populations of this species are, however, considered Threatened by Brazilian conservation authorities (Fraga et al. 2015) and Critically Endangered by the IUCN. Both species have been in continuous cultivation since the mid 19th century and improved, line bred plants now dominate commercial offerings although presumably some wild plants are still taken in Brazil.

Two color forms of Cattleya schilleriana are shown above. Note the distinctive contrast veins or pinstripes on the lips of both flowers. Left, C. schilleriana f. lowii ‘Blue & Green’, grower Sunset Valley Orchids. Image: ©R. Parsons 2020. Right, C. schilleriana, author’s collection and ©image.

While young unflowered plants can look rather similar, Cattleya aclandiae has suborbicular or obovate shaped leaves and flowers directly from the apex of newly formed pseudobulbs while C. schilleriana has ovate leaves and flowers that emerge through a sheath.

Cattleya aclandiae ‘Gulf Glade’ AM/AOS outcross in the author’s California collection. Note that this and plants shown in following two images are suspended close to the greenhouse roof and are being grown warm, breezy and very bright. Image: ©J. Vannini 2020.

Cattleya aclandiae was described from a single flower and named by John Lindley to honor Lydia Elizabeth Hoare, Lady Acland of Killerton. The head gardener of her husband, Sir Thomas Dyke Acland, first bloomed it in July 1840, nine months after its introduction to cultivation from Brazil by a junior officer serving on H.M. ship “Spey”. Because some populations of this species occur in very close proximity to the Atlantic port of Salvador, it was one of the earliest Brazilian cattleyas to make it alive to England.

Another Cattleya aclandiae ‘Gulf Glade’ offspring in the author’s California collection. Image: ©J. Vannini 2020.

In his description in Edwards’s Botanical Register Lindley noted, “Of this very distinct and pretty species of the handsomest of all the genera of Orchidaceae I have only seen a single flower, to which I owe the kindness of Lady Acland of Killerton…” (emphasis mine).

The world has changed immeasurably since Lindley wrote that, and tens of thousands of orchid species have been discovered since, but I have to agree with him that fine examples of Cattleya aclandiae definitely show it to be a very attractive species and among the “handsomest” of the world’s orchids.

Nice leopard print look on a Cattleya aclandiae f. coerulea ‘Blue Sky’ HCC/AOS outcross grown by Cindy Hill and now in the author’s collection. Consistent production of good quality blues from existing lines remains elusive, as this decidedly non-coerulea example illustrates. Image: ©J. Vannini 2020.

A common mistake made by many, including Carl Withner in his monograph, is spelling the Acland estate in North Devon and associated title as “Ackland”. This, in turn, sometime results in Cattleya “acklandiae” in error (see IOSPE photos and Wikipedia entries online for notable examples of this misspell).

An exceptional Cattleta aclandiae f. coerulea. Grower, Gold Country Orchids. Image: ©R. Parsons 2020.

Cattleya aclandiae typically has single or pairs of flowers on mature plants, while mature C. schilleriana hold three to six flowers on their inflorescences. Both usually flower from early to late spring, although some C. aclandiae will produce the odd bloom or three late in the summer and into early fall. Opinions vary as to whether plants require a rigorous drying off during winter to bloom well. My experience with mounted plants in greenhouses in Guatemala and California is that only a slight reduction in watering frequency is required from December through early February to trigger normal blooming. Older plants with dozens of pseudobulbs are definitely more reliable bloomers than smaller individuals. Flowers of both species are normally pleasantly fragrant during the day although the C. schilleriana clones that I have grown emit only a very faint scent.

As far as I am aware, no wild hybrids of Cattleya aclandiae have been reported. Natural crosses have been reported between C. schilleriana with C. walkeriana to form a hybrid with pink, red or pale violet colored flowers formerly known as C. whitei (Withner, 1988). The pin-striped lip of C. schilleriana is clearly evident in this cross.

Based on lip morphology, Withner (1988) placed Cattleya aclandiae in his subgenus Aclandia together with C. velutina despite these two species sharing few other characters. Molecular phylogenies assembled over the past 15 years indicate that these two species are not particularly closely related although, together with C. schilleriana, both are now placed in the bifoliate subgenus Intermediae. Based on DNA analysis, C. aclandiae appears to be closest to C. walkeriana, C. nobilior and C. violacea (van den Berg, 2008).

Cattleya aclandiae contributes its compact plant habit, large and fairly long-lasting flowers and its very desirable sepal and petal spotting to primary hybrids. These traits continue to dominate in complex hybrids with C. aclandiae in their backgrounds.

Cattleya aclandiae f. alba ‘ex-Bela Vista’, grown by Sunset Valley Orchids. Image: ©R. Parsons 2020.

Flower size is variable, with older wild origin plants having small, very cupped flowers to 3-4”/7.5-10 cm across. Line breeding as well as colchicine or oryzalin treatment have greatly improved flower form and size and some modern examples, presumably polyploids, have flowers in excess of 5”/13 cm wide. While lateral sepals are invariably incurved/cupped, award quality flowers will have wide, fairly flat petals and dorsal sepals.

An example of a Cattleya aclandiae primary hybrid, C. Landate at Golden Gate Orchids. Image: ©J. Vannini 2020.

This species originated the miniature hybrid cattleya or Minicatt phenomenon almost 150 years ago and continues to be very popular with contemporary orchid breeders.

Cattleya Brabantiae (C. aclandiae x C. loddigesii), the first miniature Cattleya hybrid was shown by Veitch in 1863, winning a Silver Banksian Medal from the Royal Horticultural Society (Veitch 1906). Originally christened C. x Aclandi-Loddigesii and remade countless times, it remains the most popular primary hybrid involving C. aclandiae. Despite being a primary cross, many select offspring from contemporary remakes bear little resemblance to C. aclandiae. Cattleya Measuresiana (C. aclandiae x C. walkeriana, Anon. in Hort., 1899) is another of the early crosses between Brazilian bifoliate cattleyas. Cattleya Landate (C. aclandiae x C. guttata McClellan 1966) is one of the later noteworthy primary hybrids.

Cattleya Peckhaviensis (C. Marriott 1910) is a beautiful C. aclandiae x C. schilleriana hybrid that combines the sepal and petal spotting of the seed parent with the rich, striped lip of the pollen parent. Easier to grow and flower than C. aclandiae, some examples of this primary hybrid are exceptional. This hybrid has also been backcrossed to both its parents with apparent good results in terms of plant vigor and flower color in F2.

Cattleya Brabantiae Sentinel’s ‘Hot Pants’ AM/AOS. A remake of a classic 19th century hybrid between C. aclandiae and C. loddigesii that–unlike most C. Brabantiae–bears little resemblance to either parent. An old friend of mine (Q.E.P.D.) in Guatemala used to jokingly call garish-looking cattleyas like these “putonas” (= flashy hookers). Author’s plant and ©image.

A specimen plant of Cattleya aclandiae ‘Paul’ HCC/AOS x ‘Gulf Glade’ AM/AOS grown by Cindy Hill, now in the author’s California collection. Aerial roots shown here are just under 48”/1.25 m in length. Image: ©J. Vannini 2020.

Both Cattleya aclandiae and C. schilleriana excel as mounted subjects, either in open wooden baskets, on cork slabs or hardwood branches. They should be grown as bright as possible short of burning, with plenty of water and nutrients when in growth as well as excellent ventilation at all times. While somewhat tolerant of intermediate conditions, these plants thrive in fully warm tropical environments. In my experience C. schilleriana is better suited to pot culture than is C. aclandiae, which tends to languish when confined to closed containers. This species can develop >4’/1.25 m long aerial roots when fully mature and given free run. Predictably, they resent root disturbance and are very probne to transplant shock. Whenever possible, transfer of potted plants to mounts should be timed to coincide with onset of new growth, but plants even so be aware that plants may stall for a year or more. Plants that fail to flower and/or retain leaves for several years are signaling suboptimal conditions.

The two most common primary color variants of Cattleya aclandiae have light green or bronze colored petals and sepals splashed with dark brown or black spots. Less commonly seen are plants having yellow or gold colored ground color on sepals and petals. Until fairly recently, most of the high color forms of C. aclandiae tended to be very dark (f. nigrescens) selections such as ‘Black Rook’ and ‘Black Tetra’. As these heavily marked selections have been further crossed, some plants have emerged where the light ground color has been overrun and show nearly concolorous dark brown or black petals and sepals. The chance occurrence of coerulea forms in the past such as ‘Blue Sky’ HCC/AOS, ‘Blue Surprise’ and others among batches of typical colored seedlings has prompted a number of crosses targeting blueish flowered offspring. Despite decades of select breeding, this has proven a rather hit or miss effort, and good quality f. coerulea remain rare and rather expensive. Both alba and albescens forms have also emerged from line breeding programs in the U.S. and Brazil. While true albas will lack any markings, as shown here, the albescens forms will generally exhibit ghost spotting on their pale green sepals and petals.

An admittedly beautiful complex modern bifoliate hybrid involving Cattleya aclandiae that seems to have run a multi-multi-generational marathon just to end up back at the starting point. Rhyncholaeliacattleya (Rlc.) Yuan Dung Python ‘Sweetgreen’ (C. Green Emerald x Rlc. Waianae Leopard) flowering at Golden Gate Orchids. While admittedly easier to grow than C. aclandiae it is nowhere near as fragrant. Image: ©J. Vannini 2024.

A nicely colored if somewhat cupped flower form of Cattleya aclandiae f. nigrescens ‘Black Rook’ x ‘Black Tetra’, a recent addition to the author’s collection and still potted (sort of, anyway). Both parents are favored by breeders of this species seeking to contribute their very dark sepal and petal colors to offspring. Author’s plant and ©image.

Two very dark flowered examples of Cattleya aclandiae. Left, a very large f. nigrescens in the author’s collection and right, f. coerulea grown by Y. Peralta. Image: ©R. Parsons 2020. Several named C. aclandiae clones have sepals and petals with almost no light ground color visible.

Two line bred Cattleya aclandiae with bronze and pale orange ground color on their petals and sepals. Author’s collections and ©images in Guatemala (‘Mocca’ outcross shown left) and California (‘Richter’s Best’ outcross shown right).

Two example of Cattleya aclandiae f. coerulea showing lip color variation. Left, grown by Gold Country Orchids and image ©R. Parsons 2020. Right, ‘Blue Sky’ x self, author’s collection and ©image.

Cattleya aclandiae f. alba ‘SVO’ x self. Author’s plant. Image: ©J. Vannini 2025.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Ron Parsons for providing some of his always amazing images of cultivated plants in private collections in California to this article. Thanks also to Cindy Hill for passing along some exceptional Cattleya aclandiae clones that she grew for over a dozen years, as well as to Tom Perlite of Golden Gate Orchids in San Francisco for providing a matchless environment in which to grow rare tropical plants.

An 5”/12.5 cm wide flower on Cattleya schilleriana ‘Alphri’ SM/JOGA, an outstanding selection of this species with saturated flower color and excellent substance that was awarded a Silver Medal by the Japan Orchid Growers’ Association. Author’s plant and ©image.

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC® 2020-2025, ©Jay Vannini 2020-2025, and ©Ron Parsons 2020-2025.

Follow us on: