Swamp Lion

That’s One Small Step for Man…

by William W. Lamar

Image: ©William W. Lamar 2024.

Autumn leaves were busy turning and dropping, but summer’s last gasp still made me break a sweat. Before we set off from the rickety shelter at an abandoned deer-hunting camp, my friend Steve and I arranged our sleeping bags alongside colossal, trash-filled dens of Eastern Woodrats (Neotoma floridana). We entered a far-west Louisiana forest, hard on the border with Texas, that looked unremarkable from a distance. But this was no run-of-the-mill briar patch. The terrain dropped abruptly and a game trail descended, winding into the maw of a massive ravine. Trees of average height turned out to be merely the upper portions of gigantic American Beeches (Fagus grandifolia) groping skyward from the bottom of the gulch. We had crossed into another world, a silent high-domed cathedral pocked with cylindrical Beech trunks; their smooth, gray bark dressing them like towering Roman pillars in the deep shade. Muted by the quiet, we picked our way wordlessly to the bottom. Our footsteps and the symphony of whispers whenever a breeze scuttled and hoisted the falling foliage were the only sounds.

American Beech (Fagus grandifolia). ©Stuart Anthony/CC 2006.

The forest floor, bright with honey-blond Beech leaves, fought off the gloom. Millions of them, flat, ovoid and serrated, had changed like chameleons from their bright green summer finest to create an immaculate flaxen carpet. The burble from a clear stream gently broke the reverie. An outsized paw print of a Louisiana Black Bear (Ursus americanus luteolus) sharply stenciled the dirt where the bruin had halted to drink. Squatting to study it, we saw Beech mast all over the place. The triangular nuts encased in spiny husks must have made an opulent smorgasbord for forest denizens from mice, squirrels, and Eastern Chipmunks to Black Bears, deer, foxes, ducks, and Bluejays. Turning to step over the creek, Steve was in the lead.

I jerked him backward mid-stride.

Thinking it was a prank, he spun to face me but followed my stare and realized he had been about to step squarely on a large snake. It lay like a scaly cinnamon roll; a perfect, tight coil, steeped in somber hues and nestled among the grainy Beech leaves beside the water. The reptile sensed our presence but opted to remain motionless—with nary a tongue flick—relying on crypsis for protection. I gazed at this miniature naturescape, a still life that could have been Thoreau’s rendered musings, or an Elliot Porter photograph, with each leaf flawlessly positioned and everything, including the pitviper, perfectly placed.

Recoiling, Steve quipped, “Oops! Don’t tread on me!” - which triggered some thoughts, so let's digress...

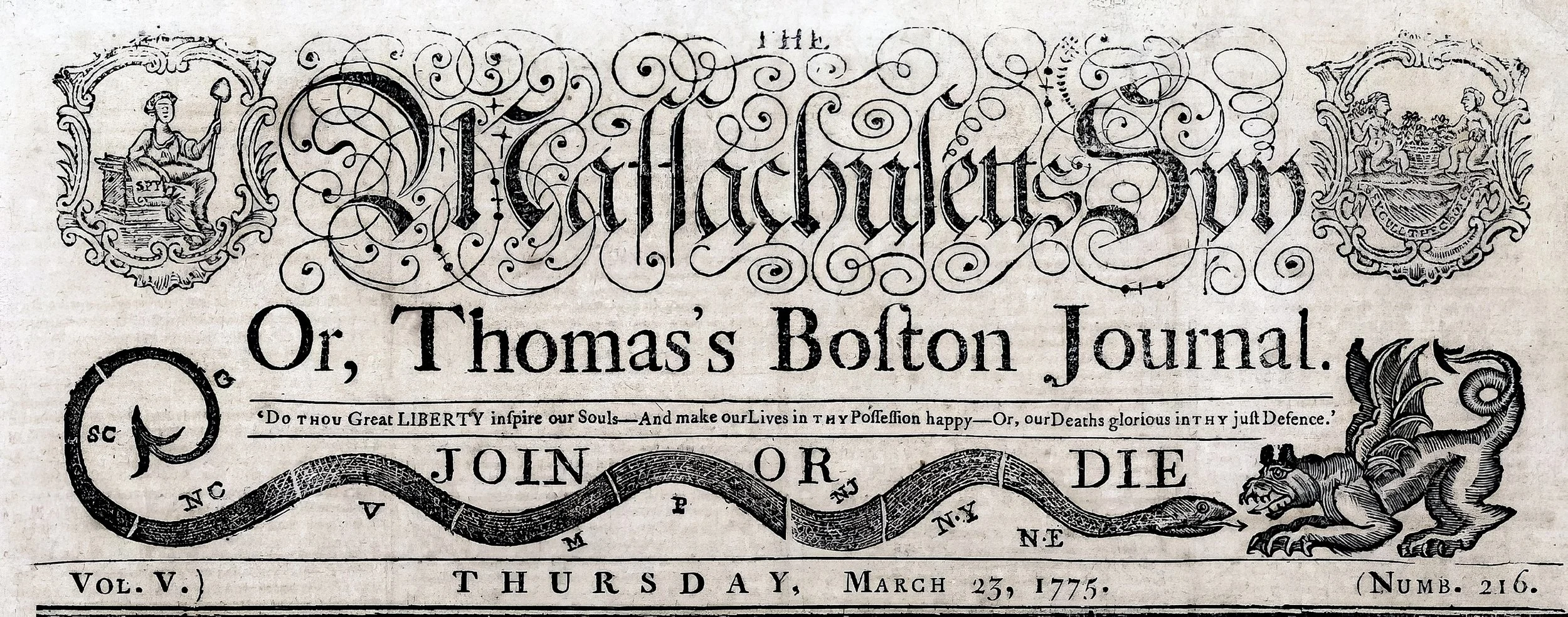

Make no bones about it, Benjamin Franklin was thoroughly ticked off. And he had every right to be. During the period leading up to a metastatic cascade of conflict—the local French and Indian War begat the global Seven Years’ War that eventually led to The American Revolution—the Colonies were busy being fractious, self-centered, and short-sighted (sound familiar?). So the cerebral Franklin, who always saw the big picture and realized Colonial unity was imperative, made a cartoon. Published alongside a scolding editorial in his newspaper, The Pennsylvania Gazette, it depicted a snake, chopped into eight pieces, each representative of a colony or region, all aligned in a symbolic map.

And it carried this exhortation: “Join, or Die.”

Ben Franklin’s famous cartoon depicting the fractious, self-centered, needlessly divided colonies prior to gaining independence from England. The message translates to “united we stand,” and that is as true today as it was in the 1700s.

He probably didn’t do the engraving himself; his idea may have come from Nicolas Verrien’s Livre curieux et utile pour les sçavans et artistes (Paris: 1685), which featured a portrait of a snake in two pieces, or other French emblem books that included mottos like “Nec mors nec vita relicta [Neither death nor life abandoned]” and “Se rejoindre ou mourir [Rejoin or die].” An additional influence may have been illustrations of rattlesnakes by naturalist Mark Catesby. It is possible he melded these notions with the prevalent myths about the so-called Glass- or Jointed Snake (Ophisaurus sp., actually a legless lizard with a fragile tail) to create a reptile in multiple pieces that might be able to reconnect. The day of its appearance, in 1754, Franklin was preparing to participate in the Albany Congress for the express purpose of dealing with the French threat and discussing a treaty with the Iroquois Confederacy. The cartoon’s message, picked up and published by several newspapers, caught on and grew as Colonists and other Native Americans plus the British fought the French. And it continued when the Colonists battled the British and gained independence.

Franklin’s image caught fire in the mind of the public and was quickly repeated, in one version or another. This one, from the Massachusetts Sun, appeared at about the time of Gadsden’s flag and featured an additional colony. The banner shows the colonies in a face-off with a demonic looking British griffin.

By that time, “Join or Die” had become an ironclad American symbol of patriotism and unity.

So it’s likely this weighed on the mind of an aggressive young merchant in Charleston, South Carolina. Born into wealth and privilege, Christopher Gadsden was fed up with British meddling and extortion. He became a political activist and member of the Sons of Liberty, the Stamp Act Congress, and eventually the Continental Congress. Gadsden led or aided in several anti-British movements including resistance to taxes and control, plus a widespread boycott of their goods. And he joined the military as a colonel but eventually rose to the rank of brigadier general, helping to defend Charleston against potential threats during the French and Indian War. However, Gadsden is best remembered because he designed a remarkable flag during the American Revolution, which he presented to Commodore Esek Hopkins, commander-in-chief of the Continental Navy, in 1775.

On a yellow background it featured the spiraling coil of a gaping rattlesnake above the admonition:

“Don’t Tread on Me.”

Back then, the uninformed populace feared all snakes, just as they do today. But the rattlesnake, with its weird caudal device, was right at the top of their list. Gadsden chose the notorious pitviper as a symbol of resistance and strength. And the warning embodied the American sentiment in favor of individual liberty and against British repression; it was essentially Franklin’s snake in one piece. Aside from its adoption by the Continental Marines, the Gadsden Flag would become a ubiquitous symbol of patriotism and independence. Indeed, over the years the arresting image has continually been resurrected to suggest resistance and defiance of the status quo by movements around the world that range from boring to extreme, our age being no exception.

Gadsden’s famous flag has been made many times over. This one hails from Civil War times.

The word "Crotalus," of Latin origin, and name of the genus that includes most rattlesnakes, can be traced to ancient times. It derives from the Greek word "κρόταλον" (krotalon), which means "rattle" or "castanet." This refers to the distinctive noise produced by rattlesnakes when they vibrate their segmented tail appendage as a warning signal.A "crotalum," is a music maker also known as a "crotale." Crotales are tuned percussion instruments commonly used in orchestras, chamber music, and sometimes in popular genres. They are typically made of bronze and look like small cymbals. Given our long-standing egocentric propensity for adorning other forms of life with human intent and emotion, it is unsurprising that the percussive whirr of a rattlesnake, actually a genteel heads-up, has become an acoustic symbol viewed as harbinger of imminent doom. So, it was only natural for Gadsden to select a rattler for his celebrated flag.

But I think this was an error...let me explain.

The Timber (or Canebrake) Rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus). This Mississippi specimen represents the paler colored southern population. The species is one of two candidates for the snake on Gadsden’s flag. The snake is coiled defensively, with rattle raised and ready for action. Image: ©William W. Lamar 2024.

Gadsden’s stylized snake makes identification practically impossible, so there is continuing disagreement as to which species it represents. One of the two candidates, the Timber Rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus), has such a protracted cultural history that it has rightfully been dubbed “America’s Snake”. Known by around two dozen vernacular names (plus others lost to history), this pitviper has figured in tales (mostly tall), rumors, remedies, and even carried a bounty on its head. We die-hard southerners like to call our local population, larger and paler than its northern cousin, the Canebrake Rattlesnake. Other monikers range from descriptive (Velvet Tail) to pejorative (Bastard Rattler). Canebrakes occur in Gadsden’s native state of South Carolina and are present in the Low Country environs surrounding Charleston, his birthplace.

The Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus). Largest of the rattlesnakes and one of the world’s heaviest venomous snakes, this magnificent creature was common where Gadsden grew up, so it is possibly the model for his flag. Image: ©William W. Lamar 2024.

Another more imposing and less secretive candidate would be the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus). With a more limited range than the Canebrake, this snake is a native of the low coastal plain. I vividly recollect that they were abundant during my Charleston childhood, so one can only imagine how frequently these pitvipers might have been encountered some two centuries ago. Largest of the rattlesnakes (they’re rare, but I’ve seen a couple of seven-footers.), these splendid creatures tend to leave a lasting impression on anyone who encounters them. Like most wildlife, today’s diminishing numbers accompany smaller maximum sizes, but back in the 1700s there must have been some veritable Low Country giants. Minimally, via his military activities, it seems likely that Gadsden had seen his share of wildlife and it is probable that he was familiar with the Eastern Diamondback. Beyond a doubt, one of these two rattlesnakes served as model for the Gadsden Flag.

Enter the Swamp Lion!

This candidate missed the cut for the flag, but richly merited consideration. Humans don’t see very well and it is safe to say that the overwhelming majority of snakes escape our detection. Ideal venues for reversing this are roads and waterways, where things tend to stand out because there is no shelter. Perhaps owing to that, the Cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus), an accomplished swimmer, has had at least three dozen vernacular names applied to it. Water Moccasin is frequently used, and some favorites from past times include Gapper [sic], Stump-tail Viper, Swamp Lion, Congo, and Trap-jaw. Quintessentially North American, but silent unlike its sibilant rattlesnake cousins, this semi-aquatic pitviper has starred in countless lurid stories. Many are set in frigid environs where the species does not exist; and most depict behaviors and feats never performed by any Cottonmouth.

Survival hint: Never correct a muscular local when they trot out these yarns; they’re considered sacred family treasures by many.

It has been rendered in works of literature, art, and popular culture symbolizing mystery and the darker aspects of nature. All depict this venomous snake as sinister and menacing. Indeed, the presence of several harmless but imposing species of watersnake has only served to expand on “Cottonmouth” sightings in the mind of the lay public who simply cannot tell the difference. Identification is an admittedly challenging skill, especially with a wriggling, unhappy specimen. Its reputation as a belligerent adversary is perhaps unrivaled by any other North American species. While normally nowhere near the size of its two rattler relatives, the corpulent Cottonmouth is nonetheless a substantial snake. They are generally solitary and primarily nocturnal hunters. Cottonmouths can be found in or near water in the southeastern U.S., including salt marshes, barrier islands, and mangroves; but they favor swamps, weedy bayous, secluded creeks - most any wet, woody place.

A Western Cottonmouth - the Swamp Lion – gapes. This snake, member of a notably dark population hailing from Mississippi’s Issaquena County, reveals the startling contrast of a whitish mouth lining. This likely serves as warning to those about to tread upon the snake. Image: William W. Lamar 2024.

Aptly described by late herpetologist Raymond L. Ditmars as “omnicarnivorous,” these phlegmatic creatures will consume practically anything they can subdue. And that includes fishes, amphibians, mammals, alligators, turtles, and even their own kind. But for the hurdle of size, they would undoubtedly engulf bathers and their canoes. Resilient, adaptable survivors, they can be locally abundant. Considering our perpetual slaughter of wildlife, especially the legless variety, and destruction of habitat, that’s saying a lot. I recall struggling through acres of slimy swamp forest and mire to reach a drying pool on a Tennessee peninsula known as President’s Island, in the Mississippi River. The number of Cottonmouths attracted to it by trapped fish was astounding and I captured twenty-five in as many minutes.

In broad daylight.

Much like the Louisiana snake in the Beech forest, this Texan Cottonmouth is coiled and at rest...precisely where it would be easy to accidentally tread upon! The paired dots visible at the apex of each scale are tiny pits whose purpose is not fully understood. Among other things, they might assist in pheromone detection during the mating season. Image: ©William B. Montgomery 2024.

Much of the notoriety garnered by the Cottonmouth centers around its behavior when approached. Confronted in or near the water most will prudently flee, but others tend to coil or remain that way, with head tilted upward. They often gape, exposing the pale lining of the mouth. Contrasting with the generally obscure dorsum of the snake, this dramatic white display likely serves as a startling mechanism; a silent warning, perhaps. It also may facilitate data gathering for the trigeminal nerve via openings in the roof of the mouth that provide the snake with vital information. Whatever, it makes quite an impression on humans (see vernacular names). Despite the portrayal on the Gadsden Flag, rattlers don’t gape, unless one counts the occasional fang-realigning yawn. The snake Steve almost trampled finally tired of being inspected by two bipedal giants, so, chiseled head cocked back, it gaped. We knew its identity but that white mouth, stark against the dark coils, would have eliminated any doubts. It was a Western Cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus leucostoma), the Swamp Lion. So a gaping Cottonmouth, as opposed to a gaping rattler on the flag would have been more accurate, at least where mouths are concerned.

The Western Cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus leucostoma); alert, tongue gathering intelligence, this formidable pitviper is ready to defend itself. Authorities squabble as to whether the Cottonmouth is a single species, two, or even three. This Mississippi specimen, however, is typical in appearance. Image: William W. Lamar 2024.

And there’s this “treading” business. All rules, especially those in Nature, have exceptions, but rattlers tend to sound off when about to be trodden upon. I’ve come across the occasional taciturn specimen, just as I have seen some so nervous they rattle when they might have escaped notice altogether; but these are extremes. Cottonmouths, on the other hand, do not come equipped with clappers. The herpetologists Albert and Anna Wright, coauthors of the classic two-volume Handbook of Snakes, traversed the U.S. investigating their subjects. Animals—and therefore encounters with them—were much more numerous back in the 1950s when they did their work. About Cottonmouths they made this comment: “Many times one step more and we would have been on them.”

So as potential treadees (Is that a word? Ought to be.), the nod again goes to the Cottonmouth.

And there’s this “attitude” business. Snakes aren’t great subjects when it comes to facial expressions. Subtle changes, if present at all, can generally only be detected by those deeply familiar with the subject. However, the Swamp Lion is an exception. As a matter of course it’s best to resist our egocentric custom of anthropomorphizing nonhuman animals. Sure, it’s possible to find endearing cases but it’s primarily illusory, not to mention self-indulgent. That stated, let me proceed to do so with regard to the Cottonmouth. Churlish, insolent, in-your-face, haughty...and so on.

Why am I writing this? One could simply look up “truculent” in the thesaurus and list all of the synonyms.

Better still: Guides to field identification of plants and animals usually involve a dichotomous or sequential key, that is, one constructed of paired choices involving color, pattern, or morphology. They are designed to lead the user to a name.

Here’s how one might begin where the Swamp Lion is concerned:

1. A. Eyes lidless; expressionless......................................................................................2

B. Eyes on fire; if it had hands, would give the finger to everyone...........Cottonmouth

The Cottonmouth in Beech Gulch finally tired of our scrutiny so, tail vibrating (aka rattler envy) and mouth opening and closing, it eased into the stream and slowly swam for shelter, eyeing us all the way.

Once more, the nod goes to the Cottonmouth - ready and waiting.

A mild winter day brought this silt-covered Western Cottonmouth up for basking on Texas’ San Gabriel River. Image: ©William B. Montgomery 2024.

And there’s this “aggressive” business. The term is tossed about rather carelessly, even by scientists who should know better. While cases exist of aggressive snakes, they are what statisticians refer to as outliers. That is, they are so rare and unusual we can safely affirm they involve crazy individuals, and don’t accuse me of being anthropomorphic. Years of observing reptiles and other animals have convinced me that, just like humans, some definitely have aberrant personalities. During a lifetime of close contact with quite literally thousands of snakes, I can count on one hand the number that were legitimately aggressive. And every one of them was certifiably nutso. Vigorous defensiveness is what usually prompts the confusion. Being aggressive serves little purpose, at least where survival is concerned. Just ask anyone who habitually picks fights in bars; someday someone somewhere will make them regret it, deeply. Snakes rely on their venom to subdue prey, so why waste it fighting? The Wrights once again about Cottonmouths: “We have had countless experiences with this species but have never been bitten.” I can say the same, despite having handled dozens of them.

Over half a century ago, herpetologist Clifford H. Pope made this observation: “Snakes are first cowards, then bluffers, and last of all warriors.” This, along with personal field experience, inspired herpetologists Whit Gibbons and Mike Dorcas to empirically quantify Cottonmouth behavior and their research proved unquestionably that these surly snakes prefer peace to war. Ditto that for rattlesnakes and most other creatures. Irrational negative attitudes are usually the result of perceived as opposed to actual threats from venomous snakes. Steve likely would not have been bitten had his misstep happened...not that anyone remotely wishes to take that risk.

On this we have a three-way tie.

Levity aside, there are other reasons the rattlesnake was a good choice for Christopher Gadsden’s famous flag. Insightful studies have been made about this and the widespread use of snake imagery during Franklin’s time. Back then, aside from traditional and Biblical distaste for snakes, the rural populace (in marked contrast to today’s batch of scaredy-cats) actually had reasons for their aversion. Among other things, a venomous snakebite to loved ones or livestock was often nothing short of a death sentence. Is it any wonder they rallied around the rattlesnake as a fearsome and dreaded symbol of strength, resilience, lightning response, and awesome ability to fight or die?

Bully for all of them, and for the snakes! Join or die? Seems like advice we need to revisit urgently.

But I still would have made that flag with a Swamp Lion.

A portrait of the Swamp Lion, eyes on fire. Image: ©William. W. Lamar 2024.

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC® 2024, ©William W. Lamar 2024, ©William B. Montgomery 2024, and ©Stuart Anthony/Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC 2.0 DEED) 2006.

Follow us on: