Taking a Stab at Stibnite

How the Magic Powers of Crystal “Antimoney” Brought Me Wisdom, Balanced my Chakras, and Emptied My Wallet

By Jay Vannini

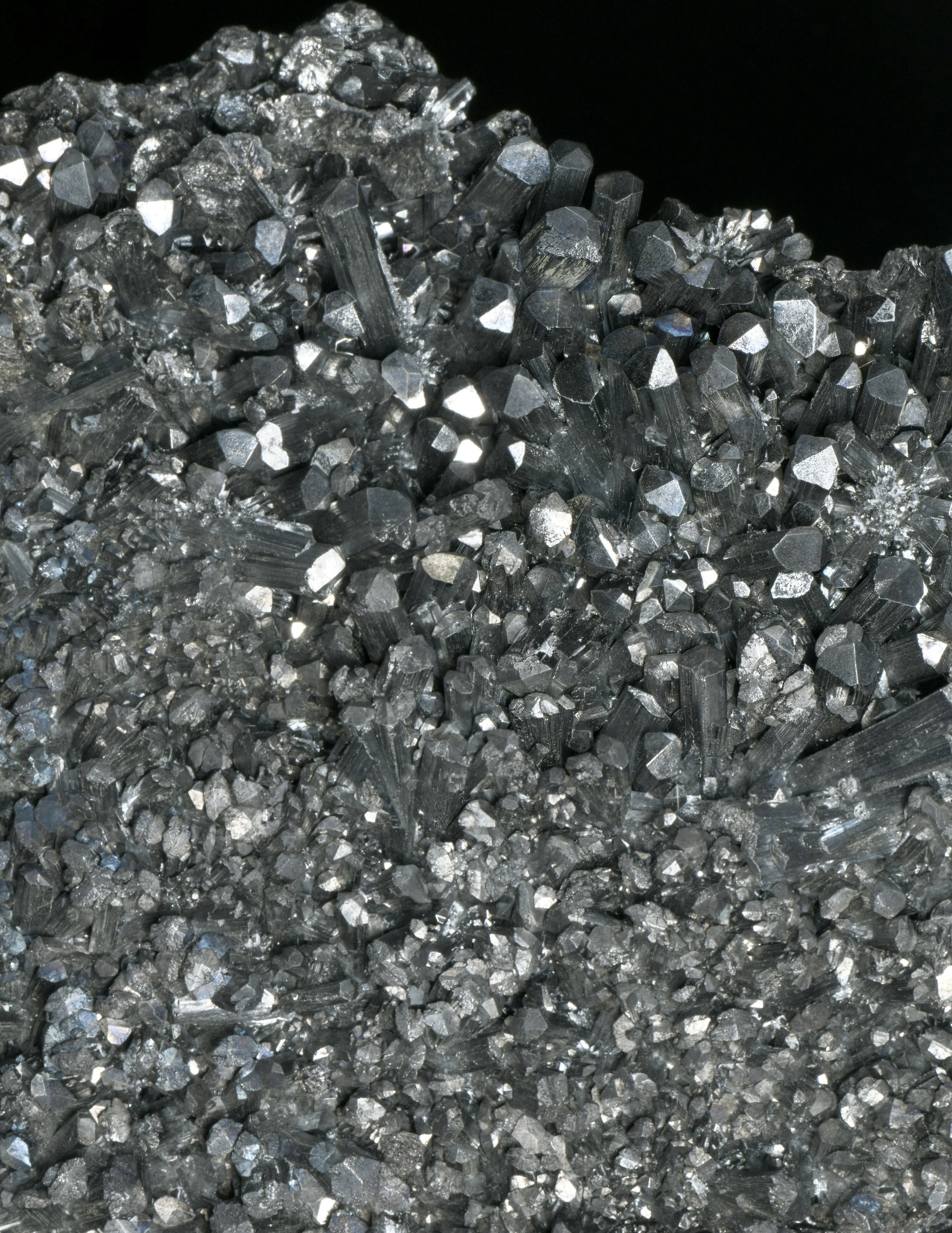

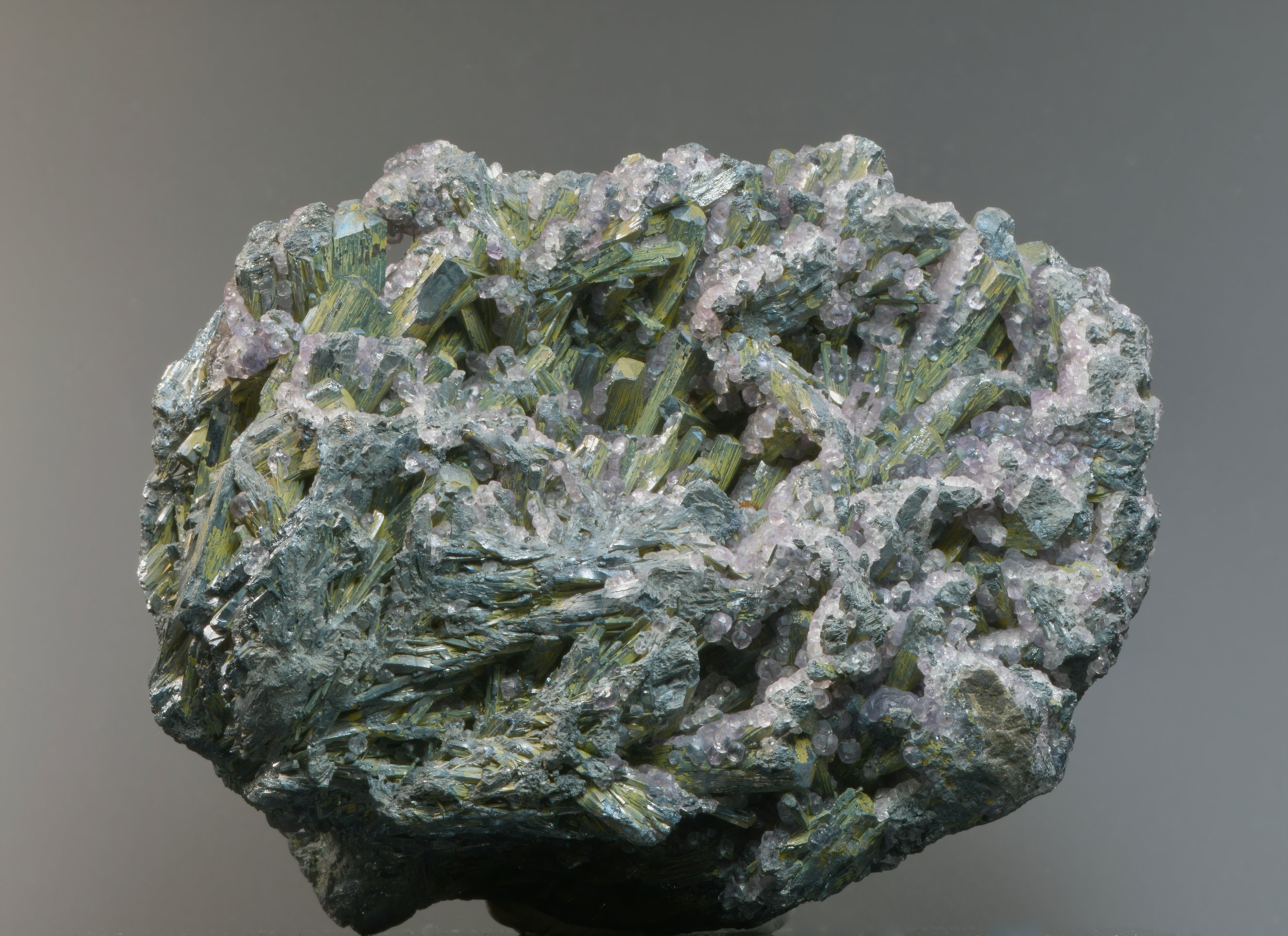

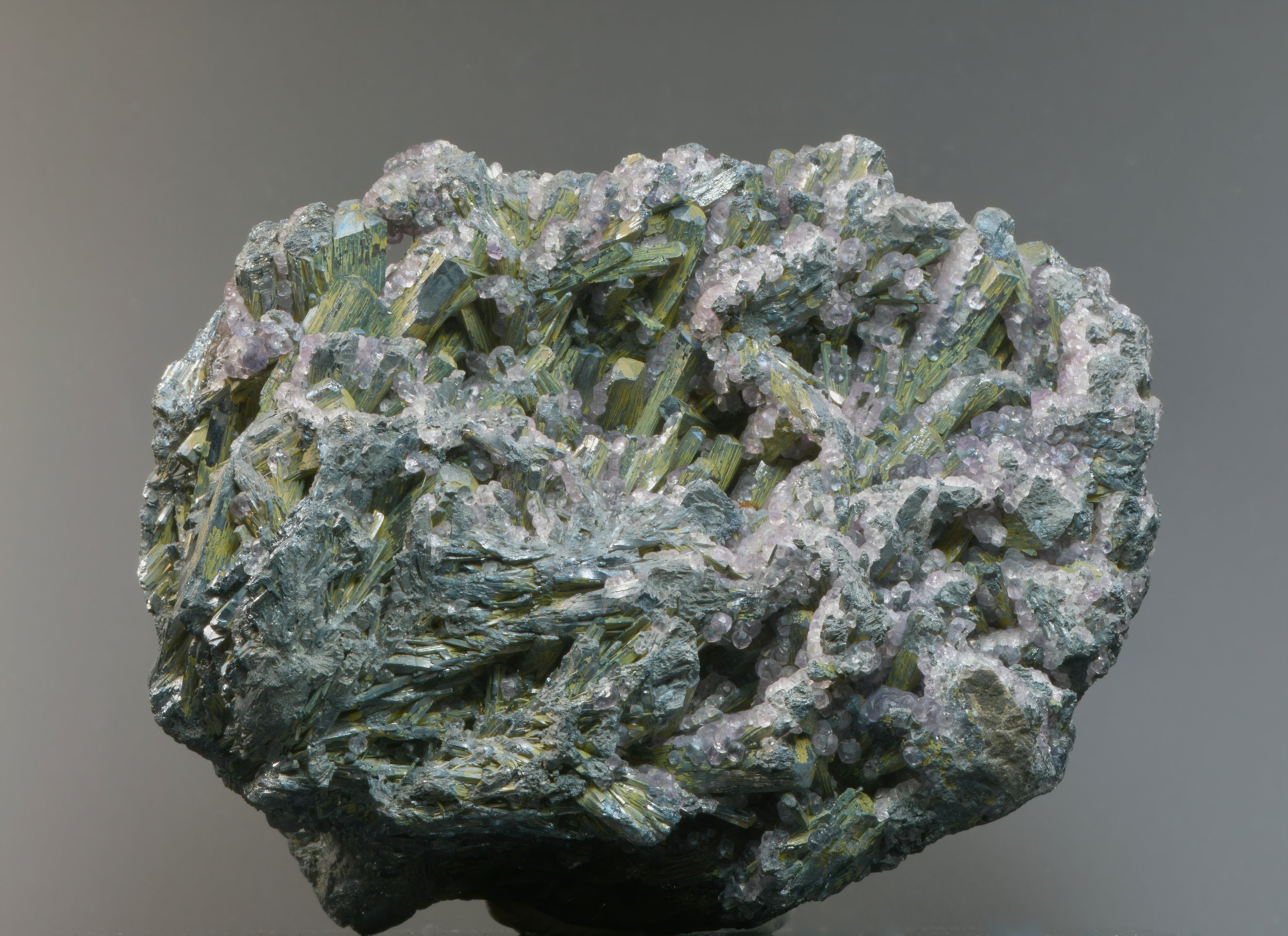

Ricci di Mare? An aerial stibnite plate with patinated radial acicular crystals on quartz and calcite base. This aggregation of crystals suspended on a skeletal sulfide mineral matrix looks very much like a tightly packed group of sea urchins. Partial oxidation and alteration visible on some crystals. Stibnite specimens such as this one are extremely fragile. Le Cetine di Cotorniano Mine, Chiusdino, Siena Province, Tuscany Region, Italy. Dimensions: 113 mm x 45 mm x 82 mm (L x W x H). Author’s collection. Image ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Flawless and luminously gemmy or lustrous examples of rare mineral species are universally appealing and generate considerable visual impact. They are quite literally the spotlit rockstars of gem and mineral show floor displays everywhere and frequently grace the pages of glossy magazines focused on interior décor, collectibles, and nature. High end specimens of rhodochrosite, tourmaline, beryl, fluorite, rose and smoky quartzes, filigreed crystalline gold and silver wires, together with malachite, azurite, and many others have very compelling aesthetics. They are often described in the media or touted by some mineral dealers as “Nature’s Art” and “Investment Grade” Minerals.

Amateur mineral collecting is one of the original keystones of the centuries’-old construct of the gentleman’s natural history cabinet, a wide-ranging set of pursuits often considered elitist, eccentric, or arcane by the uninitiated. These cabinet sets include assembling study collections of such trophies from nature as seashells, fossils, butterfly and beetle carcasses, pickled reptiles, amphibia and fish, bird eggs and skins, pressed botanical specimens, etc. While the fashion dates from the early Renaissance, in popular culture this type of systematic “bird and bug” collecting conjures up images of prosperous but severe-looking men with white hair, big bellies, bigger whiskers, and sepia-tinted Victoriana in general. Beyond this stereotype, some of us come from the school where every well adjusted young boy should have a box of cool-looking rocks stored under his bed, a sun-bleached armadillo skull on his bedside table, a pressed prickly pear flower in his copy of the “Field Guide to the Birds”, and a pet horned lizard thermoregulating in his pants pocket.

So, is mineral collecting still just one more annoying “guy thing”?

While even in recent times interest in geology and rare mineral collecting – other than the collection of cut gemstones and precious metals – were almost exclusively the province of men (e.g., me), this demographic imbalance has changed dramatically over the past couple decades. Inspired by pioneers such as British geologist Dr. Janet Watson (d. 1985), female geoscience graduates are now increasingly represented in the field. Growing numbers of knowledgeable and enthusiastic women amateur mineral collectors arrive on the scene each year, alongside more graduate women field geologists, geochemists, etc. Several well-respected public mineral collections as well as specialized publications focused on minerals and geology have female curators, directors, editors, or senior staff members.

Likewise, the groundswell of interest by New Age Believers in the advertised benefits of “Healing Crystals” has also fueled greater participation by younger women and men in mineral collecting (Persson, 2022). Whatever one thinks of the claimed metaphysical properties of crystals, there is little doubt that purchases of baubles like colorful quartzes, dyed agates, geodes, and faceted semiprecious stones can be gateway drugs to developing a serious interest in the world’s mineral diversity.

Grumblings from crusty old malcontents aside, all these changes are positive developments for the hobby over the long-term, no doubt.

The concept of Designer or Decorator Minerals as visual anchors in modern homes was once restricted to exhibiting items like massive amethyst-loaded geodes and polished slabs of lapis lazuli in mansions, but greater awareness and appreciation of the incredible diversity of color and form in collectible minerals has expanded interest in exhibiting showy, lesser-known species to the middle class.

Which brings us to stibnite.

I’ll get the technical stuff out of the way first. The chemistry-averse reader may want to skip the first couple paragraphs.

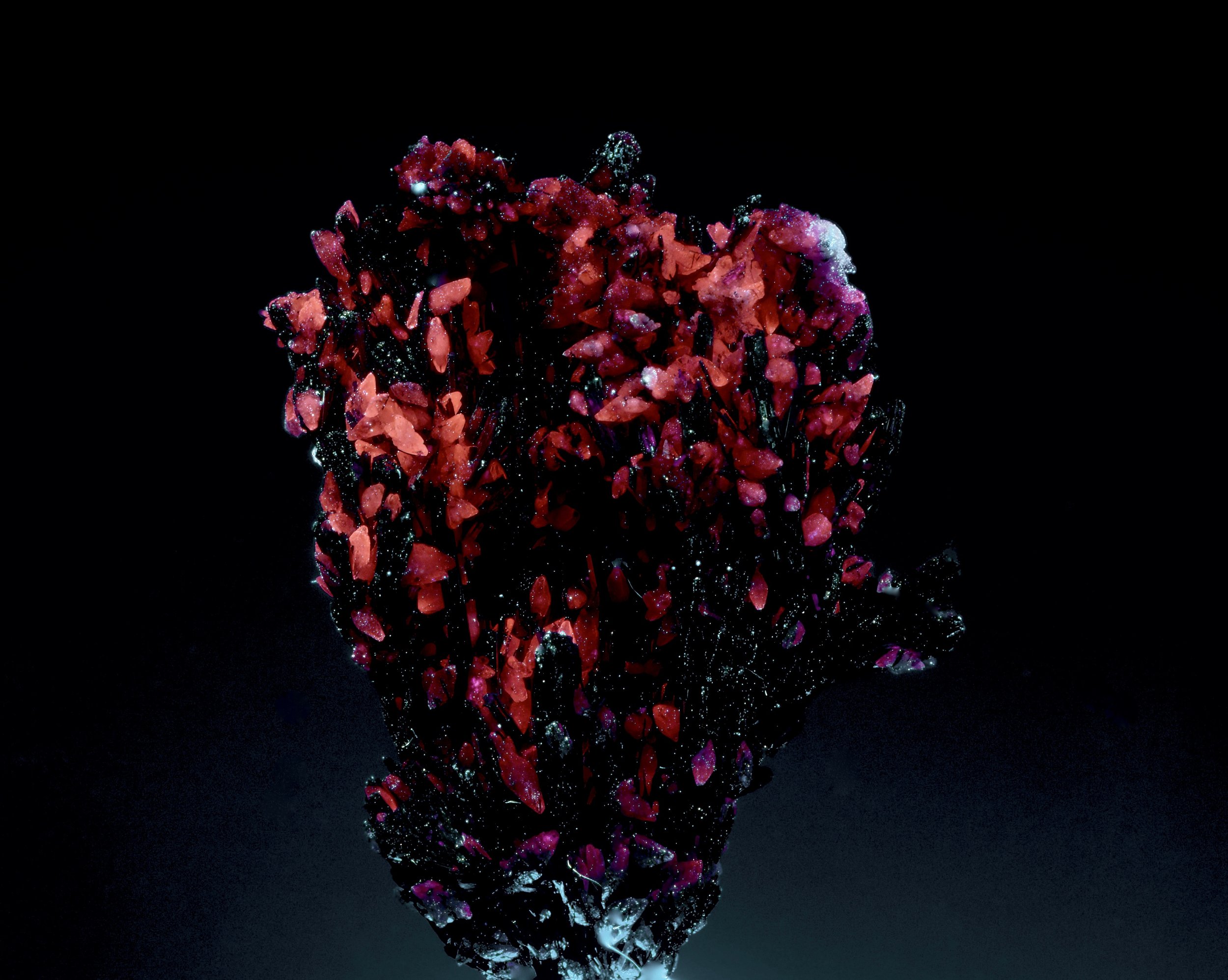

Metastibnite is a relatively rare dimorph of stibnite with amorphous crystals that occurs at many of the better-known commercial antimony mines that produce specimen stibnites. Often brick red or reddish in color in western U.S. and Italian specimens, as shown in the gallery below. San José Mine, Oruro, Cercado Province, Oruro Department, Bolivia. 46 mm x 16 mm x 62 mm. Author’s collection. Image ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Stibnite is a sulfide mineral, in this case a compound of antimony and sulfur – antimony trisulfide (Sb2S3; pardon the font format limitations that make the formulas referenced here look odd) – as is its rather rare dimorph, metastibnite. It is the principal ore source for antimony, and is sometimes called antimonite or stibine in older reference works and by a few parochial European and Chinese mineral dealers. Stibnite from some localities may contain trace quantities of metals including lead, copper, silver, and gold (Parker, 2020).

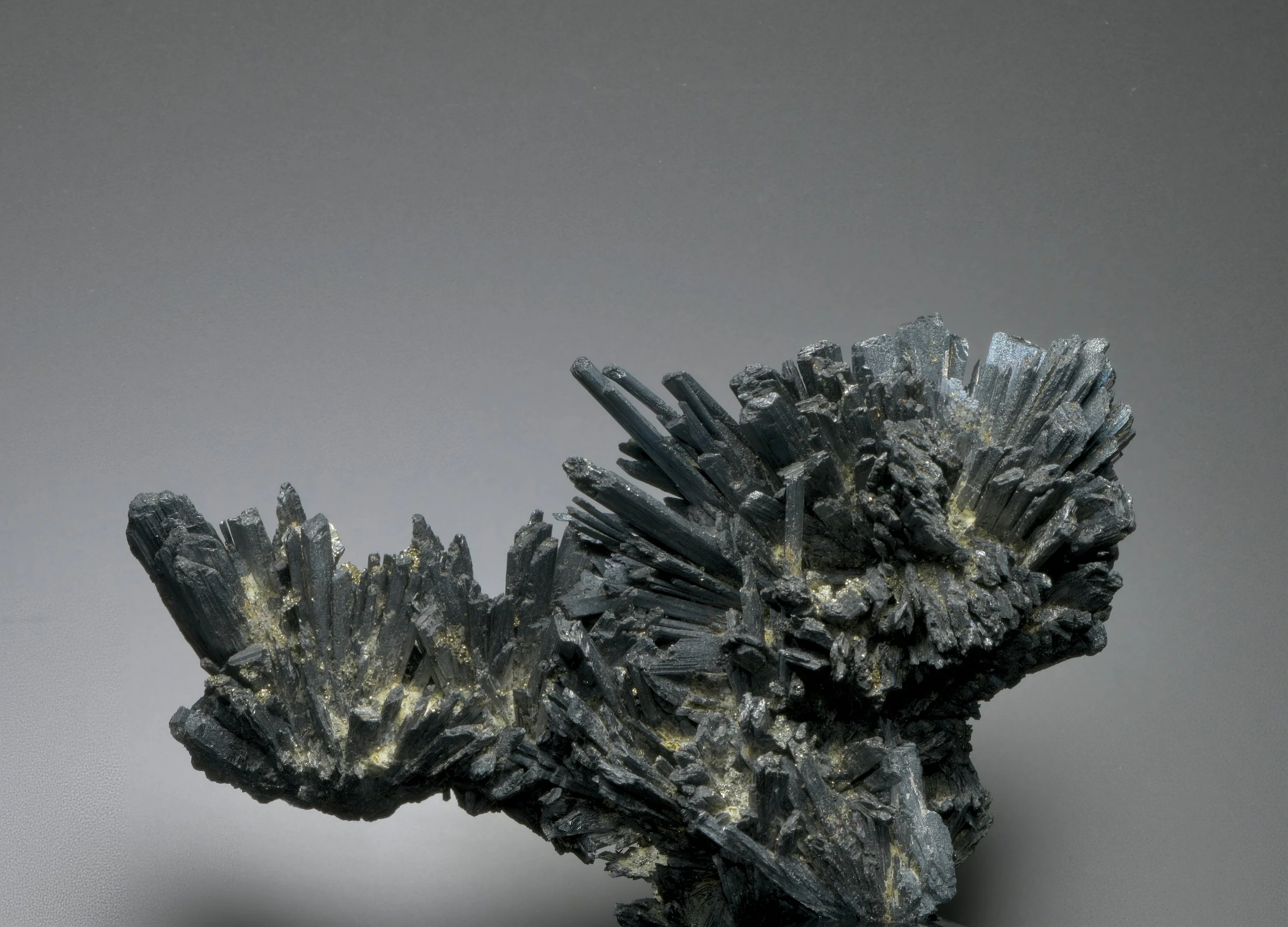

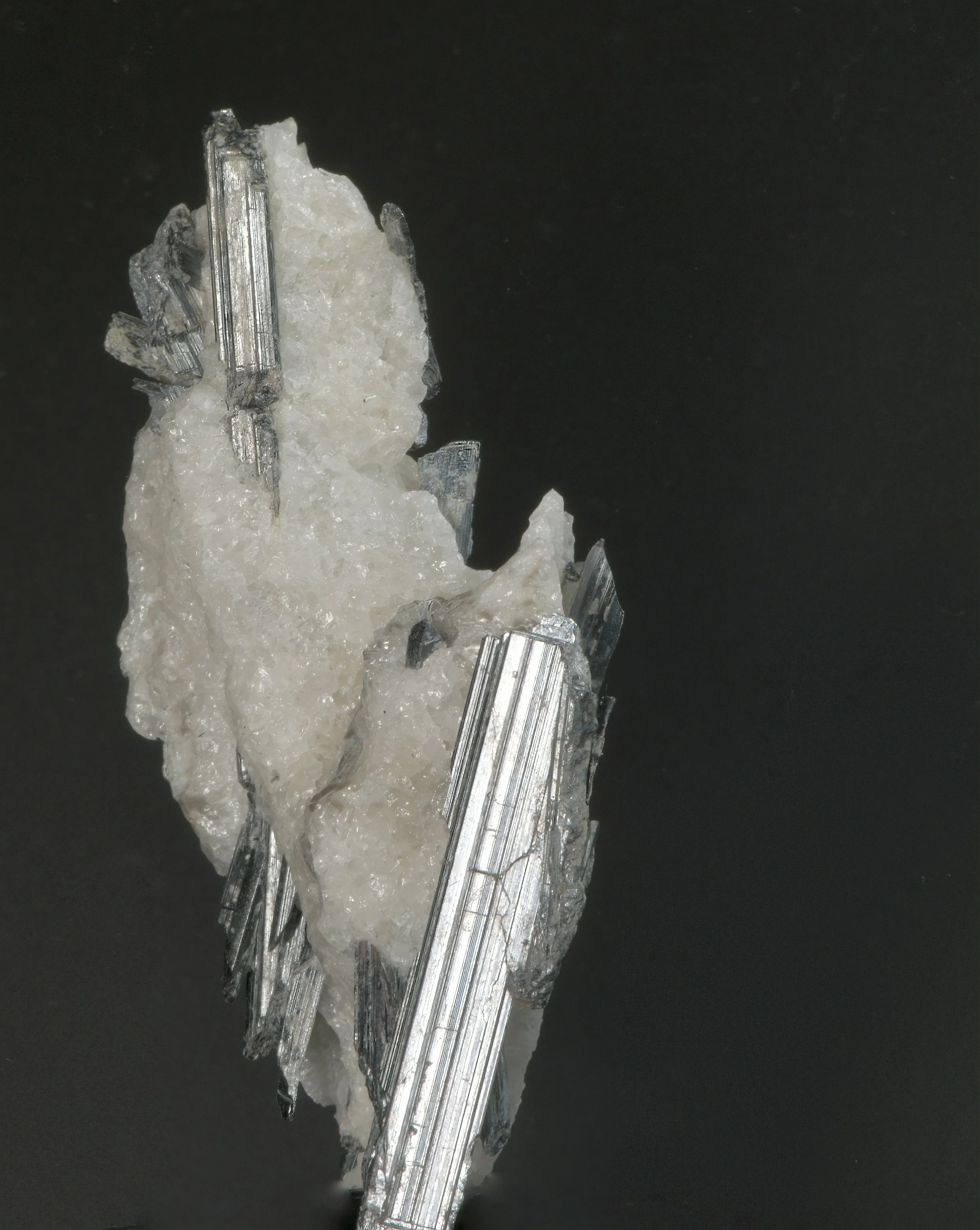

Other Stibnite Group minerals like bismuthinite and antimonselite can share the needle-like (acicular), starburst crystalline forms of some stibnite specimens. Stibnite has prismatic, markedly striate, and orthorhombic crystals that may or may not be sharply terminated. Related or derived minerals with fan shaped or plumose crystal groupings like kermesite (Sb2S2O) can be confused with stibnite and metastibnite when their crystal colors are dark. Stibnite may also bear a superficial resemblance to – and even be misidentified as – several mostly unrelated minerals that can also produce similar sprays of bladed or acicular silver-colored crystals such as chalcocite, pyrolusite, berthierite, and jamesonite (mindat.org, 2023; pers. obs.). Recent (~2018) discoveries in China’s Guizhou Province of transparent blades of the selenite variety of gypsum included by hematite phantoms were sold/are still offered by some vendors as being stibnite-included specimens. In some cases the resemblance, largely the product of an optical illusion when seen at certain angles, is indeed remarkable. That said, at least a few examples apparently do have stibnites embedded in the crystals (pers. obs.). Clear or translucent selenite crystals included by genuine stibnite are also known to occur in Perú, Italy, and elsewhere.

Sprays of stibnite fully included and penetrating pure quartz crystals on barite from the Quiruvilca Mine, Santiago de Chuco Province, La Libertad Department, Perú. The group of pincushion-like spherical crystals that dominate the center of the image are completely encased in roughly-finished but water clear quartz. Apart from quartz, included stibnites are known to occur in calcite, barite, fluorite, gypsum var. selenite, and senarmontite. Field of view (FOV) 38 mm x 27 mm. Author’s collection. Image ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Despite it being a lesser-known mineral, most everyone has observed one of stibnite’s common applications when they strike some brands of modern safety matches, since it is stibnite powder that provides the spark to fuel the fire in match heads (Ottens, 2007; Compound Interest, 2014). It is also used in pyrotechnics to give white and blue star sky glitter as well as other “sparkly” aerial displays (Pyrodata, 2023). Antimony itself is a very valuable strategic commodity used in advanced munitions manufacture, the formulation of certain key alloys, in semiconductor production, in lithium-ion battery manufacture, as a flame retardant, in the manufacture of industrial glass and ceramics, etc. (Parker, 2020; Blackmon, 2021). Recent reports show that more than 75% of all antimony used for industrial purposes in the U.S. ends up in flame retardants and bullets/artillery rounds. At this time the U.S. relies entirely on imports for its antimony needs, other than about 15% of total usage that is derived from recycled lead-acid batteries (USDI/USGS. 2022a).

A well-conserved plate of densely-packed stibnite crystals looking like a box of antique, handmade nails. This somewhat unusual piece is from the Dachang Mine, Qinglong County, Qianxinan, Guizhou Province, PR China. FOV 46 mm x 61 mm. Author’s collection. Image ©Jay Vannini 2023.

From early Antiquity until recently, powdered stibnite was mixed with animal fat and frankincense gum to make the cosmetic kohl or kahol, that dramatic-looking black brow and eyeliner often seen depicted in ancient Egyptian art. Kohl may also be called surma in parts of India and Pakistan. Contemporary native kohl mixtures substitute either powdered charcoal or lead sulfide (Yikes!) for ground stibnite despite widespread prohibition of its use due to lead’s toxicity and the very real risks posed by its ready absorption through the skin (Navarro-Tapia et al., 2021). As an aside, stibnite derives its species name from the Greek and Latin words for antimony, stibi and stibium, which in turn are corrupted versions of antimony’s unpronounceable ancient Egyptian name.

While antimony potassium tartrate, commonly known as tartar emetic, was widely used in early traditional and patent medicine from the Middle Ages until the early 20th century, other than in research, antimony’s toxicity limits its modern pharmaceutical usage. As a component of sodium stibogluconate it is still widely administered outside the U.S. under the brand name Pentostam®, or alternately as meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime®), for treatment of leishmaniasis, a very nasty protozoal disease common in some tropical regions (Rais et al., 2000). I have several friends in Central America who received lengthy courses of injections of pentavalent antimonials for treatment of ulcerative leishmaniasis lesions and all described the side effects as being on the far side of “extremely unpleasant”.

Stibnite occurs throughout the world, usually in low temperature hydrothermal deposits and hot springs that can be rich in mineral diversity. Large deposits are rare. For one example of its association with thermally active landscapes, among the better known sources for collectible stibnites until the late-2000s, the Baia Mare area mines of Transylvanian Romania, are known to overlay significant geological and geothermal resources (Kovacs & Fülöp, 2009; Neukirch et al., 2022). For one age reference, stibnite mineralization at one mining region in the Austrian Alps is estimated to have occurred in the Early Miocene, so over 20 million years ago (Sosnika et al., 2022).

Nicely-terminated, intergrown, and clustered columnar stibnite with a small field of transparent platy barite on a pyroxene mineral group matrix. Would you like freshly-grated parmesan cheese on that? A small section of peripheral damage visible on the upper right on the main crystal, but otherwise intact throughout. the Wuling/Wuning Mine, Qingjiang, Wuning County, Jiujiang, Jiangxi Province, PR China. 52 mm x 36 mm x 108 mm. Author’s collection. Image ©Jay Vannini 2023.

At an estimated 60,000 MT of mine production in 2022, mainland China is currently the largest producer of antimony by a very wide margin when compared with its two nearest competitors, i.e., 3X the Russian Federation’s same year production, and almost 4X that of Tajikistan (Garside, 2023a). The combined output of these three BRICS member countries represents almost 90% of all antimony produced globally in 2022 (Garside, 2023b). The immense geopolitical implications of these figures should be obvious to anyone who understands antimony’s critical military industrial applications and is paying attention to current events (see Blackmon, 2022 for an alarmist’s perspective). Since the last mine closed in 2014, the U.S. has not had a commercially viable domestic source for antimony, and its known reserves are dwarfed by those of all three major producers (USDI/USGS, 2022a). Despite cheerleading by the Department of Defense and other U.S. government agencies, a recent proposal by Perpetua Resources intent on reactivating antimony production in Idaho remains a very contentious issue (Robertson, 2023).

China is a correspondingly large producer of specimen-quality stibnites for both local and global fine mineral markets. Other countries with sizable antimony deposits may not produce any real numbers of collectible stibnite specimens. Canada is one good example of this, with only a tiny number of small specimens known from mines in that country, e.g., the Giant Yellowknife Mine in the Northwest Territories, and the Lac Nicolet Antimony Mine in Québec. The paucity of excellent quality stibnite specimens from the Russian Federation is another puzzling case (anon., pers. comm; mindat.org, 2023). Conversely, Kyrgyzstan is a statistically unimportant commercial producer of antimony, but has produced a fair number of showy and decent-sized clustered stibnite specimens from small mines scattered about in the southwestern part of the country.

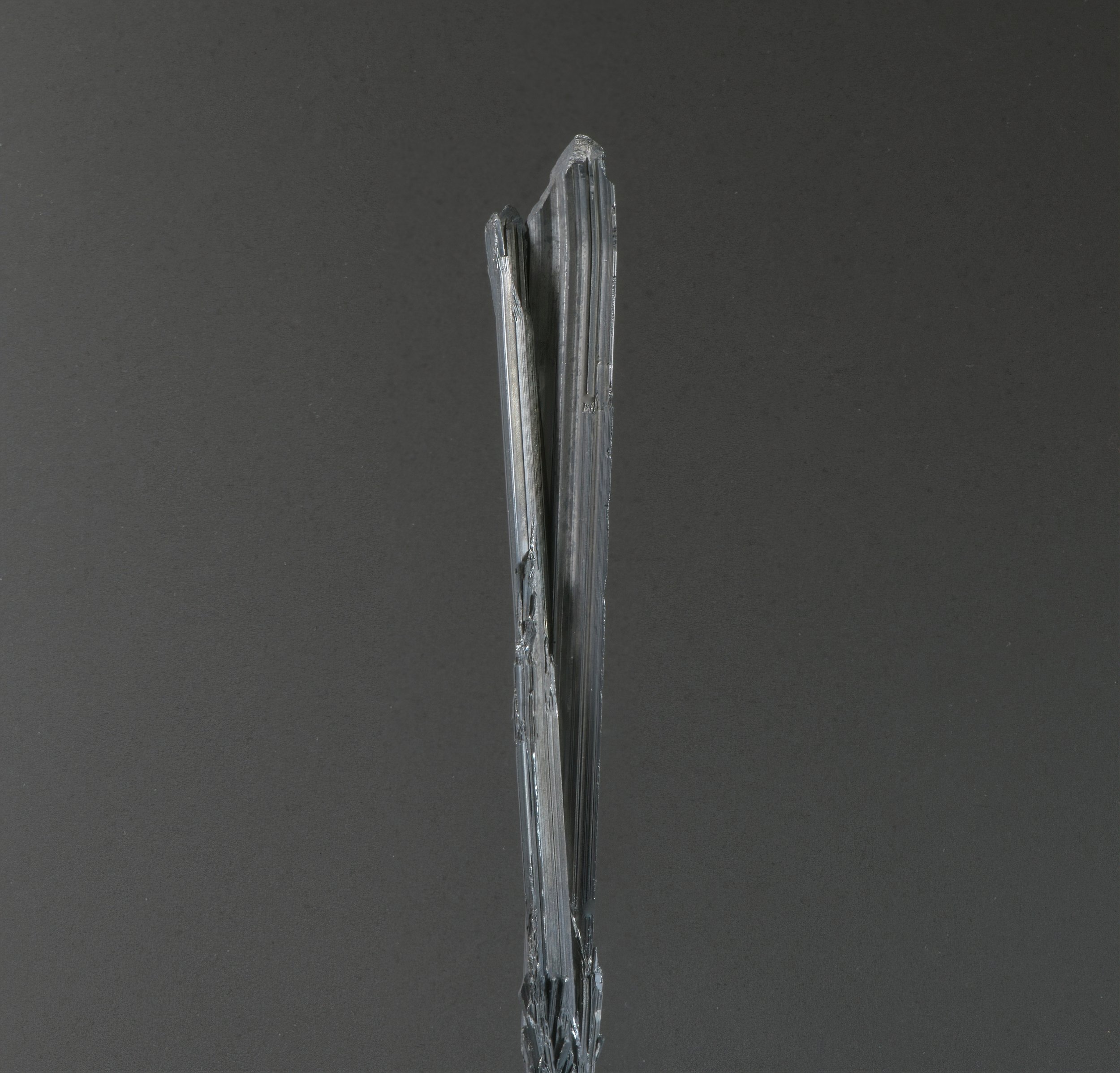

Notwithstanding its deceptively rigid and steely aspect, stibnite is sectile and very soft; 2.0 on the Moh’s Hardness Scale with an absolute hardness of 2. For comparison with a common mineral familiar to many readers, quartz is 7.0 to 7.5 on the Moh’s Scale with an absolute hardness of 100, so it is ~50X harder than stibnite (Bonewitz, 2005; mindat.org, 2023). Its perfect cleavage planes permit molecular slip (also known as translation glide or transference along glide planes) and curved, bent, and corkscrewed individual stibnite crystals are not uncommon (Parker, 2020; pers. obs.). Gradual, constant application of pressure with a piston in a Stage Strain Device will also readily deform stibnite blocks under laboratory conditions (McQueen et al., 1980).

Two examples of color extremes in stibnite specimens that also show both jagged, unterminated (left) and sharply-terminated crystals (right). Specimens from the Quiruvilca Mine, Santiago de Chuco Province, La Libertad Department, Perú, and the Chashan Mine, Dachang Polymetallic Ore Field, Nandan County, Hechi Prefecture, Guangxsi Province, PR China. Author’s collection. Images ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Stibnite is an idiochromatic mineral, so it is self-colored by its primary component elements rather than due to trace impurities or optical effects. Usually thought of as a lead-gray or silvery mineral, stibnite is quite variable in color depending on origin and evolution of tarnish due to exposure to open air. Crystals may be true black, blue-black, dull blackish-gray, matte gray through to various gunmetal gray tones with or without blue or golden iridescence, and on to mirror-finished chromium silver color. Oxidation will, over time – although often a long time – tarnish stibnites not held in specially controlled environments. Stibnites are often found frosted with adhesions of other minerals, commonly including calcite, sulfur, barite, quartz, dolomite, fluorite, and pyrite; more rarely with gold, and arsenic. Especially attractive are the sheafs or sprays of very dark, acicular stibnite blades seemingly winter snow-blown with masses of lenticular or fused rhombohedral calcite crystals from several now-closed Romanian mines, especially Herja and Boldut. They are also seen, albeit far less frequently on Chinese, Japanese, and Mexican specimens.

A pair of stibnite specimens with similar crystal habits and associated bright pyrites from two different regions. Left, Dachang Polymetallic Ore Field, Nandan County, Hechi Prefecture, Guangxsi Province, PR China (74 mm x 31 mm x 49 mm) and right, Băiuț Mine, Maramures County, Transylvania, Romania (92 mm x 47 mm x 59 mm). Author’s collection. Image ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Native sulfur on a large stibiconite group. Xikuangshan Mine, Lengshuijiang County, Loudi, Hunan Province, PR China. 162 mm x 66 mm x 99 mm. Author’s collection. Image ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Where extensive oxidation has occurred in its native environment, stibnite is commonly replaced or altered by stibiconite/antimony oxide (Sb3Sb5+2O6 [OH]) to produce a far harder pseudomorph at several localities, or when coated with elemental sulfur, give the crystals a vivid yellow or yellowish-green color. Good examples of both forms dressed this way can be most attractive. The validity of stibiconite as a recognized mineral species remains a subject of debate (mindat.org. 2023), and it may be seen in print bracketed by quotation marks. In some cases, biooxidation/alteration of stibnite can be the product of microbial action caused by Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (Torma & Gabra, 1977), as well as other microorganisms.

Stibnite may replace other minerals (e.g., galena) as a pseudomorph at some localities in the Americas.

An interesting – if somewhat damaged – legacy stibnite associated with sub-botryoidal calcite from a rare locality: The Kusa Mine, Bau, Kuching Division, Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo. The calcite matrix fluoresces pale pink at 365 nm wavelength UV exposure. 44 mm x 27 x 75 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Mines that yield high quality, collectible-grade stibnite crystal formations are relatively scarce. Countries that produce (or have produced in the recent past) examples of notable stibnite specimens in any real quantities include Japan, China, Kyrgyzstan, Romania, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Italy, Germany, the U.S., México, Perú, and Bolivia. Many of these origins no longer produce commercial quantities of stibnite ore – nor even small crystal specimens for that matter – and most high quality material being offered on the market originates from several active or recently closed mines in China. Japanese, Romanian, and Bolivian stibnites sold today are almost all from older deposits that are now shuttered or otherwise inaccessible to mineral collectors (anon. pers. comm.; pers. obs.). Likewise, worthwhile examples of Peruvian and Mexican stibnite tend to trickle to market on an irregular basis rather than be routinely carried as mainstream offerings. Collection and sales dates shown on some of the tags I have received that accompany stibnite specimens, together with informed comments by sources, confirms that much of the material from offbeat localities was collected 30 to 50+ years ago and has been recycled through several collectors’ and dealers’ hands over the decades.

Intergrown, well-terminated classic Japanese bladed stibnite from collections made in the early 20th century. These specimens are notable for their leaden color and the conspicuous striations along their lengths. Ichinokawa Mine, Saito Coty, Ehime Prefecture, Shikoku Island, Japan. 13 mm x 12 x 98 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Famous sources for world-class stibnite specimens of exquisite form and in good condition that are coveted by rockhounds are few. Those that may grant bragging rights for their owners if they’re any good include: The Ichinokawa Mine (Japan), the Wuning (also correctly spelled Wuling), Xikuangshan, Dahegou, and Chashan Mines (PR China), the Baia Sprie/Baia Mare Mine Group (Romania), the White Caps/Manhattan and Murray Mines (U.S.), the Quiruvilca, Raura, Animón, and Palomo Mines in Perú, together with the Socavón/Salvadora Mine in Bolivia.

Crystal size in stibnite ranges from microscopic crystallites to surprisingly large and heavy blades. The tallest well-documented Japanese specimens are ~24”/60 cm high. Crystals exceeding 39”/100 cm in length and 6”/15 cm in diameter are reported from the Wuning Mine in Jiangxi Province, China (Behling et al., 2002), as well as a note that “…exceptional crystals to almost 1 meter long were found…” at Lushi, Henan Province (Ottens, 2007). Many crystals over 39”/100 cm from the Feishuiyan deposit at the Xikuangshan Mine in Hunan Province, were also cited by Ottens. The massive Stibnite “Roman sword” and columnar crystals with chisel tips once found at the Ichinokawa Mine in Japan led to the colorful – if unlikely – oft-repeated tale in mineralogical circles that Japanese miners used these giant stibnite crystals as fence-posts around their gardens. Despite this claim finding its way into the literature, mineral auction catalogues, and in background color for online specimen offerings, the anecdote seems bogus. Quite apart from stibnite’s softness and perfect cleavage, Mindat.org manager and geologist Alfredo Petrov recently (August 2022) debunked this story by pointing out that Japanese miners in the 19th and early 20th century were poor, and that large stibnites are heavy and were of not-insignificant monetary value even then due to their high antimony content. While it is quite possible that a few large columnar crystals were seen stacked up at miners’ homes while en route to the smelter, it is a bit of a stretch that a valuable commodity in high demand for explosives and decorative metalware manufacture would be treated in such a cavalier fashion (A. Petrov, 2022).

A Collectible Fine Art Mineral? Careful! You could poke out someone’s bank balance with that thing.

In the broad sense of the term, stibnite is almost certainly one of the most morphologically diverse mineral species. Its astounding variety of massive, crystalline, and altered forms has few peers.

Multiple generation crystals on a “barbed wire” stibnite specimen. These types of crystal formations, while attractive, are incredibly brittle and require extreme care when handling and transporting else only a box filled with very expensive glitter arrives at destination. Xikuangshan Mine, Lengshuijiang County, Loudi, Hunan Province, PR China. 125 mm x 51 mm x 69 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

A quick glance over the images of smaller specimens (<8”/20 cm) from my personal collection shown here, followed by looking at any of the glamorous, half-million dollar museum trophies shown online should go far to explain the appeal of this mineral species to even the most hidebound non-rocker.

The best examples, even if miniatures, are deliciously complex objects when examined at close range. If mirror-finished or silvered, in specimens that are brightly-illuminated the reflections on their longer, wider crystal faces and their striations, coupled with slight changes in eye positioning by the viewer, combine for an interesting optical illusion of wave-like micro mechanical movement among the crystals.

The sculptured or architectural habit of exceptional stibnite crystal formations conjures up any number of easy comparisons to the products of human engineering and art. These range from the menace of approaching thickets of spears, the chaotic tragedy of freshly collapsed scaffolding, the sharp glint of an unsheathed Katana, explosions unleashed from artillery bursts along a forest edge, piles of girders, overflights of skyscraper-packed fantasy-scapes, immersion in the almost infinite range of gray tones and topsy-turvy perspectives of Escheresque imagery, and even…

…oh, well. You know I just have to mention it.

Even to a “Throne of Swords” in that seemingly endless recent television series.

Medium-sized, somewhat haphazardly-formed, prismatic stibnite crystal group from Romania. Crystals are quite a bit darker in color under natural light than shone under directed, bright illumination, which was used to enhance detail of individual crystals in this formation. Herja Mine, Chiuzbaia, Baia Mare, Maramures County, Romania. 185 mm x 125 mm x 70 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Then there are the crystal habits that echo other forms in nature; globes of acicular black crystals that bring sea urchins to mind, hedgehog-like crystal sprays, sheaves of elongated crystals bound like wheat stalks, the confusing jackstraw arrangements that resemble packrat nests, straw-like crystals with cross pieces that seem to mock stick insects, rosettes of well-terminated crystal groupings that recall marigold or chrysanthemum centers, and the heavily calcite-frosted Romanian specimens that look almost exactly like snow- and ice-covered conifer branches in midwinter.

Rosettes of well-terminated stibnite blades from southeastern China that are remarkably similar in habit to those of some stibnites from Romania. Chashan Mine, Dachang Polymetallic Ore Field, Nandan County, Hechi Prefecture, Guangxi Province, PR China. FOV 56 mm x 38 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Some of the larger, single or twinned bladed and very lustrous Chinese specimens almost appear man-made products of Early Modernist Architecture.

And so on.

Exceptionally large stibnite specimens composed of long, flashy crystals are aesthetically pleasing, dramatic display items and are showcased in both public and private collections around the world. Size matters. Huge, near pristine (lightly repaired?), professionally collected examples are focal points of mineral displays in the Museum of Natural History in London, at the Senckenberg Naturmuseum, The American Museum of Natural History, the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, the Harvard Mineralogical Museum, the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, the Alfie Norville Gem and Mineral Museum at the University of Arizona, and others.

A link to an image of one celebrated giant stibnite specimen shown in an AMNH blog post is included here. Using your back button will return you to this article: https://tumblr.amnh.org/post/652384893679075328/behold-the-spectacular-stibnite-fun-fact-this

As a biologist and serial collector of all sorts of nonsense, what fascinates me most about this species is the seemingly infinite variation in habit across both localities and individual crystal clusters. Ma Nature has clearly spent a great deal of time tinkering here and there with the design of this mineral and its associate matrices and I am always amazed to find yet another unique formation/habit from a blueprint that I had not seen before, even in well-stocked online galleries of mineral photos.

While Chinese localities regularly produce extra-large cabinet-sized stibnite specimens over 12”/30 cm wide, many others yield far smaller specimens as a rule. Although fine examples can exceed 15”/38 cm in height and width, most collectible northern Romanian specimens available on the market are between 2”-6”/5-15 cm across their widest points. For another example and for whatever reason, those from Zacatecas and San Luis Potosí states in central México seem particularly hard to get anything much over 3.25”/8 cm wide or tall from, despite that fact that some very large stibiconite-altered wands are not infrequently offered from the latter locality. Curiously, large stibiconite crystals to over 12”/30 cm in length are often seen offered for sale from surface workings of oxidized antimonate ores at the Estación Wadley in the Catorce Municipality of San Luis Potosí, but – due to collection limitations and biases – unaltered stibnites from the region are extremely rare in the trade.

Romanian stibnites are in a class all their own and their diversity of forms is amazing. Coincidentally, almost all originate from the Transylvanian region in the central part of the country. It obviously takes more willpower than I possess to resist the allure of chasing dusky gray or black glow-in-the-dark bladed crystals from the Transylvanian netherworld.

Like most crystal mineral species, stibnite specimens are priced based on a complex combination of criteria that includes general display quality and first-blood visual impact, overall crystal condition, specimen size, locality, presence or absence of documented accession data and chain of custody, and the relative abundance or rarity of comparable quality material on the market coupled with prevailing macroeconomic conditions at any given time. Predictably, large, showy, undamaged crystal groups from any origin with any noteworthy associated basal matrix are in high demand by mineral aficionados and can fetch six figures in US dollars, so lust and cupidity also play big roles in the market for these rarities.

In certain venues, it is not uncommon to see comparable quality stibnite specimens that are - say – 2.5X the size of specimen “A” priced at 20-30X the price of specimen “A”.

Logistical challenges also play a big role in pricing.

An almost pure mass of micro- and fine acicular Italian stibnite crystal clusters with minor quartz after careful cleaning by the author of extensive unattractive gypsum infiltration and coatings throughout. Specimens like this require exceptional care when handling and storage due to their fragility. A notable specimen for the region, reportedly collected in the early 1970s from the Capalbio Gypsum Quarry, Torre Carige, Grosseto Province, Tuscany, Italy. 125 mm x 84 mm x 72 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Exquisitely delicate minerals such as translucently-bladed wulfenites, scolecite sprays, and any stibnite with an abundance of plumose or super fine-acicular crystals are extremely difficult to transport with happy end results to both buyer and seller, even when expertly packed because they will usually shed bits and pieces with wild abandon if jarred in transit. Most stibnite specimens offered for sale usually exhibit contacts, micro-chipping, and/or peripheral or terminal damage on close examination, and even extremely well-preserved specimens will often carry at least a few tiny nicks or dings visible under magnification due to the softness of this mineral. These defects will negatively impact pricing in most cases, since exigent collectors insist on near immaculate, damage-free specimens, especially at smaller sizes.

Large, clustered stibnite specimens in superb condition, now an exclusively Chinese commodity, are costly due to their relative rarity and the incredible fragility of big, heavy specimens. Their elongated and brittle crystals make handling them a complex, labor-intensive, and expensive endeavor. Even expert collectors marvel at how large stibnite plates can make their journeys from mine faces in remote regions of the world to Western display cases in such surprisingly good condition. Damage is unfortunately cumulative as specimens pass from hand to hand over time. Micro-crystals on specimens from a couple desirable Peruvian localities, together with the “bearded” Xikuangshan habits seemingly shed their silvery, fur-like second generation crystals from even staring at them too hard if you’re in a bad enough mood. It really is a miracle they (sometimes) arrive in anything like very fine or even acceptable condition after international mail travel!

A full spray of roughly-terminated columnar stibnite with associated arsenopyrite (?) microcrystals from a fairly new find for the species in southern South America. Mina Chicote Grande, Chicote Grande, Inquisivi Province, La Paz Department, Bolivia. 90 mm x 51 mm x 85 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

These exceptional specimens aside, if you do your homework, know what you want, and are careful not to make impulse purchases, fine quality, aesthetically pleasing small cabinet to large cabinet size stibnites (i.e., 2.6-6”/6.5-15 cm maximum dimensions) can be found at reasonably accessible prices from dealers in the U.S. and EU. Expect hefty premiums to be charged for high-quality specimens with no visible damage even under magnification, and those with dimensions over 10”/25 cm that have attractive basal matrix minerals and were known to have been collected at the Ichinokawa (Japan), Wuning (PR China), Herja (Romania), or Manhattan (Nevada, USA) mines.

Mindat’s “Best of” and the Friends of Minerals’ photo galleries are always fairly good launch points to figure out what fine specimens of any given mineral species look like, including stibnite.

And again - always shop around at reputable sources! It will come as no surprise to savvy online buyers that mediocre quality, heavily damaged minerals are commonly seen grossly mispriced (and even misidentified) on eBay, Etsy, and similar ecommerce sites. Beware sellers who casually gloss over scandalous crystal damage as being of little consequence and any who constantly confuse “big and showy” with the term “museum-grade”. It should also be no shock to readers that both accidental mislabeling and intentional obfuscation of stibnite localities has been known to occur in the trade and in online articles.

Mineral collecting, like other manifestations of our genetically-programmed acquisitive nature, will find both deep disappointment from expensive, ill-considered purchases as well as lasting delight from discovering sleepers at bargain prices.

The variety of patinas on many stibnite specimens is part of their charm, but some otherwise attractive specimens may be tarnished a dull lead-gray from poor storage or natural causes and that may detract from the overall aesthetics of the piece. Chemical removal of tarnish and distracting, tiny adhesions of other uninteresting minerals with the lightest of touches, and preferably in several stages, can restore or enhance iridescence and greatly improve the visual impact of some drab-looking pieces. Collectors interested in exploring this option may want to contact and work with a specialized mineral preparation lab rather than risk ruining a valuable specimen with home chemistry experiments.

And again: Unless you want all your specimens to look like sprays of stainless steel sewing needles or new chromed bumpers on toy cars, well-patinated stibnites are best left untouched by amateur restorers.

Stibnite has something of a reputation for losing its luster over time if exposed to bright light for prolonged periods. It is best conserved through either padded storage in light-tight containers, or displayed in cases that are not constantly exposed with illumination at high UV spectra, nor receive anything like direct sunlight (anon., pers. com.; mindat.org. 2023).

“Eurasia, the largest source of stibnite by far, is a vast geographic extension with a humbling diversity of biological and geological wealth...”

Otherwise, specimen care is straightforward. Stibnites are instant dust traps when exposed to home environments, and many examples that I have purchased had lingering fibers and hairs of various types clinging persistently to their innards, some of which are showcased here despite my best efforts. I routinely pass all new acquisitions under 365 nm wavelength UV light to, a). check for any interesting fluorescence on associated matrix or associated crystals and, b). to try ascertain where dust and microfibers have stuck to the specimen. Carefully-calibrated bursts of canned, compressed air, coupled with touch-ups with a sable cosmetic brush will generally leave specimens immaculate and ready for display or photography.

Conspicuously lacking from the gallery below is a jumbo-sized plate of well-terminated stibnite crystals from Japan or China. These items are generally available only in the rarefied environment of closed-door offerings over wine or cognac to seriously monied collectors. While I am obviously interested in stibnite, among my wish list of must-own goodies – frankly – I think I’d rather spring for a fully restored 1965 Austin-Healey 3000 Mk III than a big, shiny rock of any kind.

It almost goes without saying that those fortunate individuals who can, on a whim, spend well over USD 125 K for a mineral specimen can own both.

Lucky buggers.

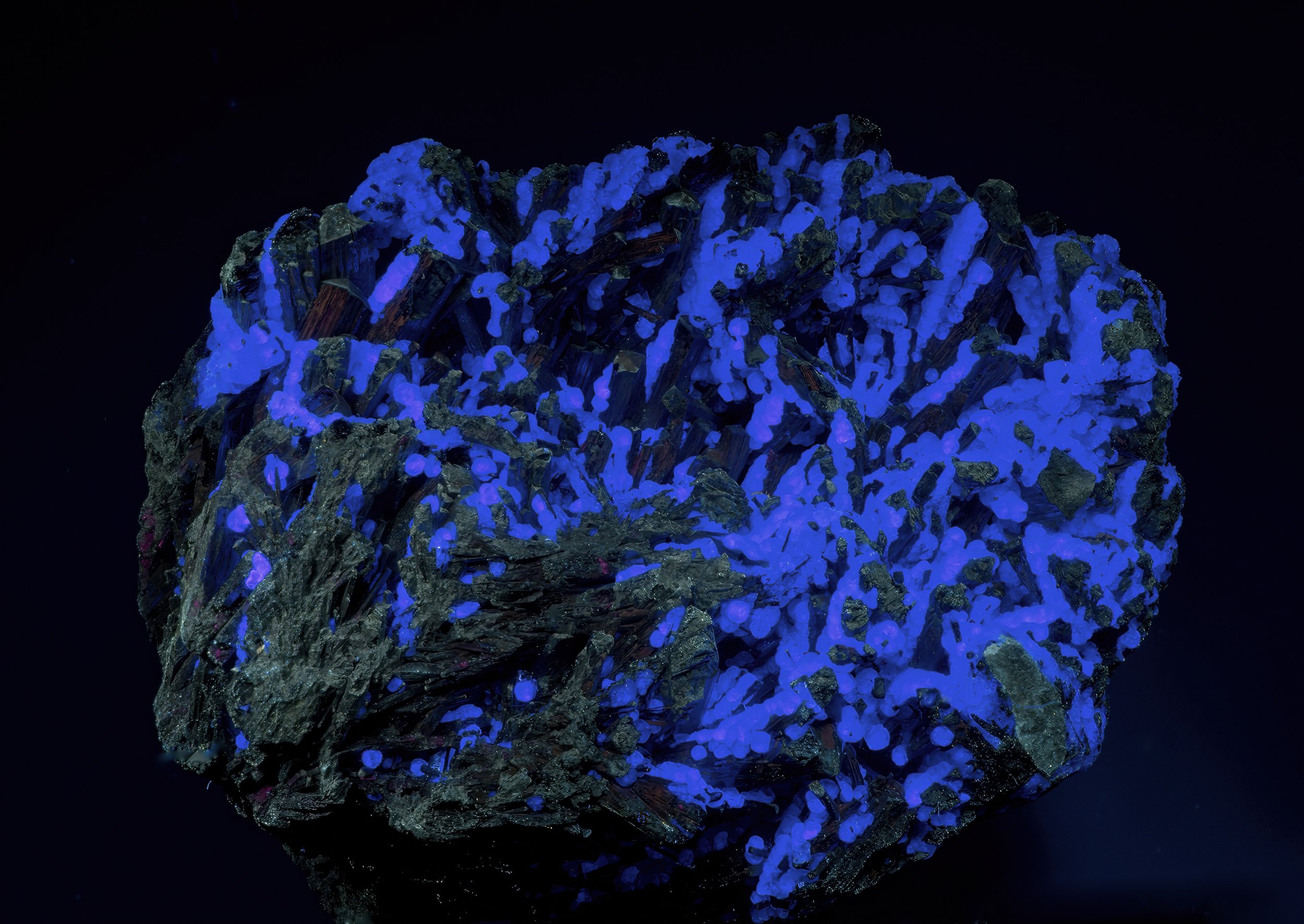

Ores don’t have to be bores. A compact and interesting chunk of massive stibnite tarted up with a luscious touch of cinnabar lipstick with lavender and white fluorite veins. All the fluorite patches visible on this specimen glow vivid blue-violet under mid-wave UV light. Some visible, partially defined bladed stibnite crystallization has developed on the lower right corner. Aydarken (Khaydarken) Antimony Deposit, Kadamjay District, Batken Region, Kyrzgyzstan. 56 mm x 33 mm x 34 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

•

Eurasia, the largest source of stibnite by far, is a vast geographic extension with a humbling diversity of biological and geological wealth, often located in extremely remote regions of the furthest back of its beyond. As noteworthy new mineral localities are discovered, ascend, decline, and are ultimately depleted or eclipsed by newer finds, future generations will perhaps look back at current gold standards for stibnite and other collectible mineral species, compare them with the finer material they have on display in their cases, and wonder what the devil all the fuss was about in grandad’s time.

Disclaimer

This topic has been addressed elsewhere by some mineralogists and dealers, but it’s certainly worth emphasizing again here.

Scaremongering is a mainstay of the internet, and there are any number of alarming, “MINERALS THAT CAN KILL YOU”-type lists populating clickbait sites. Most minerals are quite safe to handle provided basic common sense is employed, i.e., don’t rub them in your eyes, burn them in your fireplace, store them in your underwear, lick, eat nor insert them into any other orifices (only half-joking here – phallic crystal wands and polished obsidian dildos? Ouch!). Best practices dictate that you should always wash your hands properly after handling stibnite specimens for any length of time; frequent petting is definitely not a wise practice in any case due to their fragility. Despite requiring ingestion or inhalation of relatively large volumes to do serious harm to adult humans, stibnite is, after all, ca. 72% antimony by weight and antimony is both a soft and toxic metalloid.

Powdered stibnite or metastibnite-antimony trisulfide is another kettle of fish altogether and is considered a hazardous substance by regulators such as OSHA. It is highly flammable, may have dangerous chemical reactions if haphazardly mixed with other compounds, and is best handled by professionals.

We are not responsible for illnesses, injuries or death resulting from anyone conducting foolhardy, “citizen scientist” style experiments with legacy eye-shadow formulations or super-charging homemade fireworks with ground stibnite and/or any other mineral mentioned in this article.

Don’t take any risks with your rocks©.

Good hunting!

Antimony can go “BOOM”! Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

GALLERY

China

One of my personal collection favorites of this species. Massive stibnite in lower third with numerous extensive outgrowths of columnar, well-terminated crystals. A few dings, as is to be expected with an older and heavy stibnite specimen from China. An added attraction on many similar pieces from this locality are encrustations of pale lavender fluorite that exhibits spectacular blue fluorescence under mid-wave UV light and – occasionally – a few tiny ottensite crystals, one of which is visible as the orange comb middle right on the specimen. Banpo Mine, Dushan County, Guizhou Province, PR China. 105 mm x 67 mm x 87 mm, but it weighs like it’s thrice the size. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Detail showing several twisted and partially corkscrewed stibnite crystals on the specimen shown above with sulfur “enamel paint” coating, and pale lavender-colored cubic to ~decahedral fluorite crystals. FOV 42 mm x 31 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Detail of a medium-sized, tumbledown stibnite plate from one of the more common Chinese localities. This piece is heavily damaged throughout, but was the first stibnite I acquired so I give myself a “C-” for effort. Xikuangshan Mine, Lengshuijiang County, Loudi, Hunan Province, PR China. FOV 85 mm x 59 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Typical straight razor-type stibnite groupings with (mostly) terminated crystals from two well-known Chinese antimony mines. Both have superb luster and the specimen on the left is mostly damage-free. Left, the Wuling/Wuning Mine, Qingjiang, Wuning County, Jiujiang, Jiangxi Province (20 mm x 17 mm x 173 mm), and right, a 1995-vintage specimen from the Dahegou Mine, Lushi County, Sanmenxia, Henan Province, China. 40 mm x 30 mm x 182 mm. Author’s collection. Images: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

A beautiful group of well-terminated stibnite crystals from a Chinese locality that turned up these showy marigold-type formations in the early 2000s. Chashan Mine, Dachang Polymetallic Ore Field, Nandan County, Hechi Prefecture, Guangxi Province, PR China. 101 mm x 74 mm x 44 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Detail of multiple generation crystal formations on the ferocious-looking stibnite group shown earlier in the article with well-defined striations and sharp terminations. Xikuangshan Mine, Lengshuijiang County, Loudi, Hunan Province, PR China. FOV 38 mm x 27 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Japan

Not all Japanese stibnites are giant, expensive katanas and columns out of 19th and early 20th century finds at Ichinokawa. Shown above, sprays of dark and light-colored bladed micro crystals on massive stibnite with felted berthierite and non-fluorescent associated crystals. Nakase Mine, Sekinomiya-machi, Yabu City, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan. FOV 34 mm x 25 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

A lead-colored knitting needle atop some small, bent sidecar crystals from the Ichinokawa Mine. Minor damage visible on upper an lower edges, but a specimen with good patina and well-defined striations. 14 mm x 7 mm x 78 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

New Zealand

Kiwi stibnites are almost invariably a bit – shall we say –“small”. Here is a thumbnail cluster, partially altered by canary yellow stibiconite from one of the better-known localities there. Waiotahi Mine, Thames-Coromandel District, Waikato, New Zealand. 11 mm x 16 mm x 6 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Kyrgyzstan

A group of mirror-finished and “finely-tooled” Kyrgyz stibnite laid on its side showing some torsion/slippage on the tip of the middle crystal far left. Kadamzhay Mine, Kadamzhay Ore Field, Fergana Valley, Altai Range, Kadamjay District, Batken Oblast, Kyrgyzstan. 30 mm x 22 mm x 89 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Visually chaotic at first look, I agree, but lots of interesting things going on in this fantastic, cabinet-sized Kyrgyz mixed mineral plate. Apart from stibnite-included transparent barite conspicuous throughout, there are several “bent” stibnite crystals on the upper half of the specimen. Kadamzhay Mine, Kadamzhay Ore Field, Fergana Valley, Altai Range, Kadamjay District, Batken Oblast, Kyrgyzstan. 100 mm x 58 mm x 52 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Cubic pink fluorite cubes on a partially altered (with stibiconite) stibnite blade. The fluorite associated with stibnites from this locality glow beautifully under mid-wave UV. Chauvai Sb-Hg Deposit, Alai, Batken Region, Kyrgyzstan. 13 mm x 12 mm x 110 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Austria

A small block of solid stibnite ore doing its best to display a few well-defined crystals, with even a pair of bent columnar crystals visible upper left. Austria was a major antimony producer from the 18th century through until the early 1990s. The mine at Stadtschlaining in the Burgenland Province produced some very fine stibnite specimens prior to it being abandoned in the 1980s (see below). Unfortunately, no locality was provided for this specimen, although based on habit likely Maltern, Hochneukirchen-Gschaidt, Wiener Neustadt-Land District, Niederösterreich, Austria. 49 mm x 36mm x 68 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Large, well-conserved, and documented specimens of German and Austrian bladed stibnite crystal formations are uncommonly offered, in demand and costly, especially when compared to nicer looking material available from other origins. This is a small but interesting solid block of stibnite with a scattering of well-defined, jackstraw crystals across the top. 72 mm x 65 mm x 56 mm. Antimony Mine, Stadtschalining, Oberwart District, Burgenland Province, Austria. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

France

An unusual and colorful mixed stibnite specimen from a rare locality, likely collected over a century ago. Stibnite with sulfur (possibly some metastibnite alterations as well) and small quartz var. smoky crystals. Mine de la Forge, Anzat-le-Luguet, Issoire, Puy de Dôme, Auvergne-Rhône-Alps, France. 91 mm x 47 mm x 72 mm. Author’s collection. Image ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Italy

Many Italian stibnites offered for sale are from near surface workings and are usually oxidized to greater or lesser degrees. Here is one good example of stibnite, stibiconite and touches of red metastibnite that is quite vividly-colored. Grosetto Province, Tuscany Region, Italy. No firm locality origin was provided for this piece, but it strongly resembles material from Fosso La Fulligine, Semproniano Municipality, also in Tuscany. 95 mm x 75 mm x 48 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Another Italian stibnite specimen on calcite and quartz matrix that is a bit rough around the edges, but interesting nonetheless. This piece originates from the same mine as the specimen that opens this article and is also shown below. Le Cetine di Cotorniano Mine, Chiusdino, Siena Province, Tuscany, Italy. 57 mm x 43 mm x 44 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

A different perspective of the very crowded Italian “sea urchin” stibnite plate shown at the beginning of the article showing how crystals had grown into a narrow, triangular crevice in the pocket where it developed. Le Cetine di Cotorniano Mine, Chiusdino, Siena Province, Tuscany, Italy. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Romania

Short-bladed Romanian stibnite crystal starbursts on matrix with scattered fire engine red-fluorescent calcite. Conspicuously contacted throughout, but I still find it a handsome plate that recalls several small rosetted plant species that grow as lithophytes. Baia Sprie Mine/Felsöbánya, Maramures County, Romania. 102 mm 50 mm x 78 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Snowblown, stacked metallic black stibnite crystals covered in lenticular calcite with nice rose-colored fluorescence under mid-range UV. The stibnite crystals on this specimen are so lustrous it is challenging to take good images of the plate. Herja Mine, Chiuzbaia, Baia Mare, Maramures County, Romania. 139 mm x 96 mm x 73 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Hemispherical spray of fine-acicular stibnite crystals on a crystalized silica matrix. The gold iridescence on the black stibnite crystals is even more evident in sunlight. Herja Mine, Chiuzbaia, Baia Mare, Maramures County, Romania. 75 mm x 53 mm x 78 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Serried grouping of broad, short-bladed stibnite with exceptionally sharp, chisel-tipped terminations on most major crystals. A very nice specimen that has changed hands in the U.S. and Canada several times over the past couple decades. Baia Sprie Mine/Felsöbánya, Maramures County, Romania. 91 mm x 43 mm x 60 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

A plate of what appears to be incompletely formed tabular stibnite crystals from the same mine. Close examination shows a few terminated crystals. The dealer I obtained this specimen from speculated that it might be an incomplete pseudomorph after barite. A nice find that reminds me of several stony coral species. Baia Sprie Mine/Felsöbánya, Maramures County, Romania. 103 mm x 38 mm x 105 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Stibnite crystal fans with plumose habit in parts, with minor barite. Baia Sprie/Felsöbánya, Maramures County, Romania. 70 mm x 20 mm x 65 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Classic, tombstone-type tabular stibnite crystals from the Cavnic Mine. The somewhat dull, gunmetal gray or pewter crystal color is typical for the locality, although some are surprisingly iridescent. Cavnic Mine, Cavnic Mining District, Maramures County, Romania. 74 mm x 45 mm x 62 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Sub-botryoidal clusters of stibnite with water-clear platy barite on calcite. Unusual-looking but attractive piece from this locality. Cavnic Mine, Cavnic Mining District, Maramures County, Romania. 94 mm x 61 mm x 28 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

More eccentric mineral magic from the Transylvanian mines. A handsome combination of silver and black acicular crystal sprays of stibnite, with mirror image inverted fans on a barite and quartz matrix. The basal areas of the darker fans fluoresce pale green and turquoise under 365 nm wavelength UV. A nice touch, but a perplexing source…73 mm x 66 mm x 68 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Serbia

Looking quite Japanese and very aesthetic, an old partially-terminated Yugoslav stibnite cluster showing plenty of panache despite its collection of contacts, nicks, and dings. This is another European stibnite that has been passed around on this side of the pond over the past decades. Zajača-Loznica Mine, Boranja Orefield, Krupanji, Podrinje District, Serbia. 17 mm x 10 mm x 64 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Slovakia

Micro sprays of acicular, lustrous stibnite crystals embedded in white quartz matrix. 55 mm x 47 mm x 73 mm. Zlata Bana Deposit, Prešov District, Prešov Region, Slovakia. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Spain

Fused, brilliant acicular stibnite crystals with minor stibiconite. 84 mm x 33 mm x 48 mm. La Víbora Mine, Espiel, Cordoba, Spain. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Türkiye

A conspicuously bent but well-preserved and terminated stibnite crystal from another uncommon locality. 7 mm x 6 mm x 82 mm. Mine unknown, Kuracaoluk, Burhaniye District, Balikesir Province, Türkiye. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

United Kingdom

An old, amateur-collected stibnite with stibiconite, quartz and ? from a classic Scottish locality that produced many similar looking specimens back in the day. This rather homely rock has surprisingly colorful and vivid red, yellow, and acid green fluorescence at 365 nm wavelength. Knipe Mine, Hare Hill, New Cumnock, East Ayrshire, Scotland, UK. 82 mm x 42 mm x 42 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Canada

What this Canadian stibnite ore specimen lacks in size it makes up for in added rare goodies decorating its surface. Apart from acicular crystals scattered over massive stibnite, maroon kermesite sprays, valentinite, and senarmontite crsytals dominate the specimen. Lac Nicolet Antimony Mine, Saints-Martyrs-Canadiens, Arthabasca RCM, Centre-du-Québec,Québec, Canada. 25 mm x 20 mm x 33 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

The United States

Jackstraw stibnite crystal formation from a celebrated U.S. locality. White Caps Mine, Manhattan, Manhattan Mining District, Toquima Range, Nye County, Nevada. 93 mm x 70 mm x 48 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Another specimen from the same mine, a stibnite beaver dam on (indeterminate but hard) matrix with fibrous, second-generation crystals visible throughout. White Caps Mine, Manhattan, Manhattan Mining District, Toquima Range, Nye County, Nevada. 87 mm x 43 mm x 42 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Pale blue iridescence is a feature of some Californian stibnite crystals. Columnar stibnite with calcite on matrix. A bit of missed poly fiber visible lower right…these are never obvious during cursory examinations and seemingly only appear in macro photos! McLaughlin Mine, Knoxville, Napa County, California. 55 mm x 32 mm x 64 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

A more typical looking stibnite specimen from the same locality. McLaughlin Mine, Knoxville, Napa County, California, USA. 24 mm x 25 mm x 68 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Another vintage beaver dam-type dense cluster of roughly-finished stibnite crystals on solid ore with associated stibiconite scattered throughout; this from Colorado. Mine unknown with certainty but very likely Cripple Creek, Teller County, Colorado, USA. 82 mm x 53 mm x 50 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

México

A rare locality and an extremely fragile mineral specimen, feather weight stibnite on partially-dissolved gypsum with who-knows-what else holding the matrix together. Did I mention that this piece is really, really fragile? Yucanani Mine, Tejocotes, Municipalidad de San Juan Mixtepec, Oaxaca, México. 54 mm x 54 mm x 56 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Two Mexican miniatures. Left, acicular stibnite crystals with barite from the San Martín Mine, San Martín, Sombrerete Municipality, Zacatecas, México (33 mm x 12 mm x 60 mm), and right, tabular stibnite on calcite, Salvador Mine, Charcas, Charcas Municipality, San Luis Potosí, México. 26 mm x 24 mm x 35 mm. Author’s collection. Images: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Small stibnite fans with calcite on Manganese ore. An oddball piece from southeastern México. Unknown mine, Oaxaca, México. 60 mm x 49 mm x 40 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Perú

An unusual-looking aggregation of dark, matte-finished stibnite crystals on mixed matrix from a classic locality. Despite the haphazard arrangement of crystals, several are bluntly-terminated and four of the largest crystals on both sides of the specimen exhibit second generation crystals that have reversed direction from the tips of the host crystal, recalling blades on a folding pocket knife. The dark, wood charcoal color and blunt crystal terminations are typical of many stibnites from this site. Raura Mining District, Cajatambo Province, Lima Region, Perú. 90mm x 35 mm x 76 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Spherical stibnite crystals on an interesting mixed mineral matrix. Palomo Hill Mines, Castrovirreyna Province, Huancavelica, Perú. 105 mm x 83 mm x 60 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Crystal detail on specimen shown above. FOV 32 mm x 22 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Left, columnar stibnite cluster on indeterminate matrix from the Pachapaqui Mining District, Bolognesi Province, Áncash Department, Perú. This is a poorly-known locality for stibnite located north of Raura. 50 mm x 43 mm x 66 mm. Right, typically colored stibnite for the area on partially-dissolved quartz matrix. Raura Mining District, Cajatambo Province, Lima Region, Perú. 55 mm x 35 mm x 61 mm. Author’s collection. Images: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

A handsome association of napkin-holder translucent platy and tabular barite with spherical stibnite crystals. Julcani Mine, Julcani District, Angaraes Province, Huancavelica Department, Perú. 96 mm x 92 mm x 45 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

A very blocky and well-terminated stibnite fan from a rare locality. The Casapalca Mine is known for its world-class pyrites, rhodochrosites, and galenas but quality stibnites are not usually associated with this origin. Casapalca Mine, Casapalca, Chicla District, Huarochirí Province, Lima Department, Perú. 79 mm x 31 mm x 50 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Mixed plate of stellate stibnite crystals with transparent barite, gypsum var. selenite, realgar, and chalcopyrite. Quiruvilca Mine, Santiago de Chuco Province, La Libertad Department, Perú. 180 mm x 98 mm x 30 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Another dark specimen from Raura with columnar crystals looking a bit like charred wood. Note the blunt, partially-terminated tips on the taller individual crystals this group. Raura Mining District, Cajatambo Province, Lima Region, Perú. 38 mm x 20 mm x 56 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Another of my favorite stibnites. A collection of many crystal habits ranging from acicular through bladed, dendritic, arborescent, plumose, etc. While obviously fragile, this beautiful rock is not as delicate as it looks. 102 mm x 58 mm x 66 mm. Palomo Hill Mines, Castrovirreyna Province, Huancavelica, Perú. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

A nice sheaf of columnar and bladed stibnite crystals. Quiruvilca Mine, Santiago de Chuco Province, La Libertad Department, Perú. 63 mm x 33 mm x 72 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Bolivia

Oddball, highly lustrous west Bolivian stibnite crystals showing multiple generations, inverted formations, and adhesions of transparent bladed barite on the upper part of the one on the left. 22 mm x 10 mm x 71 mm. Crystal group on the right 27 mm x 22 mm x 72 mm. Both specimens from the Salvadora/Socavón Mine, Yarvicoya, Caracollo, Cercado Province, Oruro Department, Bolivia. Author’s collection. Images: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

A gunmental gray and chisel-tipped Japanese lookalike from the 1980s. Salvadora/Socavón Mine, Yarvicoya, Caracollo, Cercado Province, Oruro Department, Bolivia. 21 mm x 11 mm x 97 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Brilliant stibnite with metastibnite and stibiconite from a recent discovery. This is a more typical-looking example from this locality than the fan shown earlier in the article. Mina Chicote Grande, Chicote Grande, Inquisivi Province, La Paz Department, Bolivia. 81 mm x 40 mm x 68 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Alterations and pseudomorphs

Stibiconite and non-fluorescent ? Salvador Mine, Charcas, Charcas Municipality, San Luis Potosí, México. 51 mm x 46 mm x 56 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Stibnite ore with partially altered stibiconite after stibnite, cervantite, quartz, sulfur, and a few klebelsbergite microcrystals. Pereta Mine, Pereta, Scansano, Grosseto Province, Tuscany, Italy. 38 mm x 35 mm x 51 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

A very well-conserved cabinet-sized specimen of Chinese stibiconite and valentinite coating. Xikuangshan Mine, Lengshuijiang County, Loudi, Hunan Province, PR China. 40 mm x 21 mm x 74 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Quartz pseudomorph after stibnite with stibnite crystals underneath and adjacent to the ps. Not apparent in this image is that the quartz is completely transparent when viewed directly from above, but is gray or black from reflection of surrounding stibnites when viewed at an angle. Quiruvilca Mine, Santiago de Chuco Province, La Libertad Department, Perú collection. FOV 21 mm x 15 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Metastibnite on stibiconite. Ferruginous-colored metastibnite is typical for Tuscan specimens. Alas, the damage! but this is common in older Italian stibnites and related. Le Cetine di Cotorniano Mine, Chiusdino, Siena Province, Tuscany, Italy. 26 mm x 19 mm x 83 mm. Author’s collection. Images: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Stibnite ore with quartz, several small stibiconite columns, and sulfur crystals. Qinglong Mine, Dachang Ore Field, Qinglong County, Quinxinan, Guizhou Province, PR China. 46 mm x 24 mm x 62 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Fluorescence

A heartbreaker with a split personality from Transylvania shown under daylight 535 nm in the late afternoon, and with the associated calcite fluorescing intensely like Hellfire at nighttime under 365 nm wavelength UV. Boldut Mine, Cavnic Mining District, Maramures County, Romania. 110 mm x 54 mm x 60 mm. Author’s collection. Images: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

One mostly finds irregularly-shaped barites on stibnite specimens from this well-known Mexican locality, but the associated calcite on some certainly is showy under ultraviolet! San Martín Mine, San Martín, Sombrerete Municipality, Zacatecas, México. 40 mm x 24 mm x 51 mm. Author’s collection. Images: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

How’s that for a day-night transformation? Specimen discussed previously from the Banpo Mine, Dushan County, Guizhou Province, PR China. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Stibiconites from the Catorce region of north-central Mexico can get big, and some are nicely yellow-colored in daylight but generally do not fluoresce much. Lord knows what coatings are generating the colors shown above under long-wave UV. San José de Wadley Antimony Mine, Real de Catorce, Catorce Municipality, San Luís Potosí, México. 10 mm x 9 mm x 143 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Coats

Transparent and pale pink platy barite crystals on stibnite. The reverse side of this piece exposes some small areas of clean stibnite. The coating fluoresces an unusual gray-green under mid-wave UV light. Cavnic Mine, Cavnic Mining District, Maramures County, Romania. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Two fine examples of roughly terminated columnar stibnite+ from China. Stibnite with calcite, Banpo Mine, Dushan County, Guizhou Province, PR China. 25 mm x 26 mm x 47 mm. Right, stibnite with barite and minor calcite, several crystals conspicuously bent or folded from the Xikuangshan Mine, Lengshuijiang County, Loudi, Hunan Province, PR China. 35 mm x 17 mm x 71 mm. Author’s collection. Images: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Avalanche! Acicular sprays of black stibnite pushing back at a cascade of pale pink-fluorescent calcite and associated barite and quartz crystals. Herja Mine, Chiuzbaia, Baia Mare, Maramures County, Romania. 112 mm x 56 mm x 76 mm. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Interesting Ores

Two good examples of pure massive stibnite from western North America. Both of these ore samples have excellent silver color and well-developed stibnite crystals exposed on their surfaces. Left, Lucky Knock Mine, Tonasket, Okanogan County, Washington (112 mm x 51 mm x 55 mm), and right, Smith Creek Dome Prospect, Koyukuk Mining District, Wiseman, Yukon-Koyukuk, Alaska. 103 mm x 55 mm x 50 mm. Author’s collection. Images: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Two other western U.S. ore samples with secondary minerals also visible. Left, a stibnite specimen from the Bloody Canyon Mine, Star Mining District, Pershing County, Nevada (92 mm x 50 mm x 54 mm), and right, dense stibnite with tetrahedrite, Chipmunk Pit, Northumberland Mine, Nye County, Nevada. 77 mm x 57 mm x 48 mm. Author’s collection. Images: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Another block of stibnite ore that ain’t a bore. A remarkably heavy - for its size - zebra-striped massive stibnite with a few well-defined (and even bent!) prismatic crystals throughout, with quartz and ? from an uncommon locality for antimony. 94 mm x 78 mm x 77 mm. Ty Gardiene, Quimper, Finistère, Brittany Region, France. Author’s collection. Image: ©Jay Vannini 2023.

All measurements taken with 150 mm Spurtar vernier calipers.

Acknowledgements

For a variety of reasons, but principally out of basic courtesy and discretion, I have omitted the names of several well-known mineral dealers who generously shared information on both the current state of the collectible minerals market overall, and the market for specimen stibnites in particular. Three of them are cited in text as “anon., pers. comm.”. My recent experiences corresponding with members of the dealer community in Spain, the U.S., Canada, and Perú have shown them to be not only extremely knowledgeable on both subjects, but also surprisingly open about providing detailed information to a pesky stranger. Many thanks to all of you “anonymous” sources who provided the stibnite specimens shown here as well as very complete background information on their origins - JV.

References

Behling, S. C., G. Liu, and W. W. Wilson. 2002. Stibnite from the Wuling antimony mine Jiangxi Province, China. The Mineralogical Record. Vol. 33, Issue 2. Pp. 139-147.

Blackmon, D. 2021. Antimony: The Most Important Mineral You Never heard Of. Forbes. 2 pp. https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidblackmon/2021/05/06/antimony-the-most-important-mineral-you-never-heard-of/?sh=64cd8e532b23

The author, who is a Senior Contributor and Analyst with Forbes Magazine, managed to turn the discussion of a critical topic – the U.S.’s over-reliance on offshore sources for strategic minerals that are also available domestically – into a jingoistic infomercial for Perpetua Resources (PPTA), a Nasdaq-listed and Idaho-based gold mining company.

Bonewitz, R. L. 2005. Rock and Gem: The definitive guide to rocks, minerals, gems, and fossils. DK Smithsonian, London, New York, Munich, Melbourne, and Delhi. 360 pp.

Compound Interest. 2014. The Chemistry of Matches. Explorations of Everyday Compounds. https://www.compoundchem.com/2014/11/20/matches/

Garside, M. 2023a. Major countries in antimony mine production 2015-2022. Statista, February 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/264958/antimony-production/

Garside, M. 2023b. Production of antimony worldwide from 2010 to 2022. Statista, February 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1241586/global-antimony-production/

Kovacs, M. and A. Fülöp, 2009. Baia Mare Geological and Mining Park – a potential new Geopark in the northwestern part of Romania. Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai, Geologia, 2009. 54 (1): 27-32.

McQueen, D. R., W. C. Kelly, and B. R. Clark. 1980. Kinematics of Experimentally Produced Deformation Bands in Stibnite. Tectonophysics, 66: 55-81.

mindat.org. 2023. Stibnite. https://www.mindat.org/min-3782.html

Despite a few apparently misreported localities shown in its otherwise superb stibnite photo galleries, this is an informative, professionally curated, and well-respected “Go-to” site for rockhounds and researchers. The gold standard for well-curated online information on global mines and minerals.

Navarro-Tapia, E. M., M. Serra-Delgado, L. Fernández-López, M. Meseguer-Gilabert, M. Falcón, G. Sebastiani, S. Sailer, O. Garcia-Algar, and V. Andreu-Fernández. 2021. Toxic Elements in Traditional Kohl-Based Eye Cosmetics is Spanish and German Markets. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021. 18, 6109. 16 pp.

Neukirch, M., A. Minakov, M. Smirnov, C. Gaina, I. Panea, A. Isac, M. Collignon, A. Zlibut, C. Coverca, B. S. Paralescu, and A. M. Henriuc Morosan. 2022. Geothermal Exploration of the Baia Mare Region (Romania) with Magnetotellurics – Responses, Analysis and 1D Models. EGU General Assembly 2022, Vienna, Austria, 23–27 May 2022, EGU22-1034. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361467044_Geothermal_Exploration_of_the_Baia_Mare_Region_Romania_with_Magnetotellurics_-Responses_Analysis_and_1D_Models

Ottens, B. 2007. Chinese Stibnite: Xikuangshan, Lushi, Wuning and other localities. The Mineralogical Record. Vol. 38, No. 1. January-February 2007. 3 pp. https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Chinese+stibnite%3A+Xikuangshan%2C+Lushi%2C+Wuning+and+other+localities.-a0158839137

Parker, R. 2020. Stibnite – The Metallic Explosion. Mineral of the Quarter. Outcrop. Vol, 69, No. 1. Pp 28-33.

Persson, P. M. 2022. An Essay on Mineral Prices. Persson Fine Minerals website. January 02, 2022. https://perssonrareminerals.com/?p=1043

A well written, informative, and wide-ranging article that covers a brief history of the pastime, the current dynamics of mineral collecting, a deeper dive into the vagaries of contemporary collectible mineral pricing, and the author’s thoughts on the future of the hobby. I came across Phillip Persson’s article after I had begun a first draft for this essay and our shared viewpoints were, in a few cases, so unnervingly similar that I was sorely tempted to rewrite the second paragraph since it almost seems plagiarized. However, because both of us address the topic of the popularity of natural history cabinets in the Victorian Era, and the “old boy” side of mineral collecting coming from quite different backgrounds in life and earth sciences – specifically biology and geology – I think our perceptions of the history and evolution of the hobby are worth comparing.

Petrov, A. 2022. My old Mineral Art. Thread on Mindat Discussion Board. August 14, 2022.

PR Newswire/Lida Resources. 2020. Lida Resources Inc. Acquires 100% Ownership of the Quiruvilca Mine, Peru. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/lida-resources-inc-acquires-100-ownership-of-the-quiruvilca-mine-peru-301086360.html

Pyrodata. 2023. Antimony trisulfide. Pyrotechnics data for your hobby. https://pyrodata.com/chemicals/Antimony-trisulfide

Rais, S., A. Perianin, M. Lenoir, A. Sadak, D. Rivollet, M. Paul, and M. Deniau. 2000. Sodium Stibogluconate (Pentostam) Potentiates Oxidant Production in Murine Visceral Leishmaniasis and in Human Blood. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. American Society for Microbiology. 44(9): 2406-2410.

Robertson, A. 2023. Deep Dive: Valley Co. mine proposal said to help clean waste & secure key mineral. Critics see flaws for environment, tourism. Boise dev/Idaho First. February 23, 2023, https://boisedev.com/news/2023/02/23/stibnite-idaho-perpetua/

Local reporting on the pros and cons of a proposal to reopen the Stibnite Mining District in north-central Idaho to provide the U.S. with a domestic, industrial scale antimony source for the first time in almost three decades. Unsurprisingly, strong opinions expressed on both sides of the argument.

Sosnika, M., S. de Graaf, G. Morteani, D. A. Banks, S. Niedermann, M. Stoltnow, and V. Lüders. 2022. The Schlaining quartz-stibnite deposit, Eastern Alps, Austria: constraints from conventional and infrared microthermometry and isotope and crush-leach analyses of fluid inclusions. Mineralium Deposita 57, 725-741. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00126-021-01076-x

A very dense read that discusses the timeline of stibnite formations at a former antimony ore mine in the Austrian Alps.

Torma, A. E. and G. G. Gabra. 1977. Oxidation of stibnite by Thiobacillius ferrooxidans. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 43 (1):1-6.

U.S. Department of the Interior-U.S. Geological Survey. 2022a. Mineral Commodity Summaries. January 2022. 2 pp. https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2022/mcs2022-antimony.pdf

U.S. Department of the Interior-U.S. Geological Survey. 2022b. Mineral Commodity Summaries 2022. USGS, Reston, Virginia. Data for Antimony, Pg. 24 https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2022/mcs2022.pdf

Vora, S. 2022. Chemical Compounds That Incite Oohs and Aahs. The New York Times. June 24, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/24/arts/design/fine-mineral-collecting.html

A striking vanity shot of a nice chrome-colored stibnite specimen from the Wuning Mine opens the article.

Zigerlig, K. 2019. Minerals are the new rock stars: History and essentials. Berkely One. 2 pp. https://www.berkleyone.com/2019/11/11/collecting-minerals-history-essentials/

Some examples of stibnite can really shine. Mirror-finished termination on a mid 1990s-era Chinese specimen. The reflected LED lighting, long exposure time, and magnification evident in this photo make the crystal’s tip look much, much worse than it does under low power magnification in daylight. Dahegou Mine, Lushi County, Sanmenxia, Henan Province, China. Author’s collection. Image ©Jay Vannini 2023.

All content ©Exotica Esoterica LLC 2023®, and ©Jay Vannini 2023.

Follow us on: